A picture of the socioeconomic trends surrounding COVID-19 in the Caribbean with a gender lens

Since recording the first cases of COVID-19 in March 2020, the pandemic has posed a heavy burden on health systems, the economy and the livelihoods of people in the region. The pandemic also has the potential of reinforcing and even worsening pre-existing inequalities within society. For example, there are accounts of women faring worse with the socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19, as they generally earn less, save less, and tend to hold more insecure jobs or are more likely to live in poverty than men (see UN, 2020; World Bank, 2020 and World Trade Organization, 2020). The prevalence of unpaid care work has also increased substantially during the pandemic, as schools have closed, and families are spending more time at home. This is having a greater impact on women than on men, who typically take on a greater burden of house tasks related to care. And even more concerning, deeper economic and social stress have led to a rise in gender-based violence.

In our latest publication, we analyze key socioeconomic indicators surrounding the COVID-19 shock with a gender lens, specifically regarding: (i) the socioeconomic impact of the pandemic; (ii) individual’s quality of life; and (iii) financial inclusion.For this analysis we make use of the online socioeconomic survey conducted by the Inter-American Development Bank between March and June 2020. Given that most of the data was collected at household level, which does not allow for an individual level disaggregation of the effects of COVID-19, we proxy gender in many sections of this paper by comparing single females to single-males and partnered couples.

Three key messages emerge from our review:

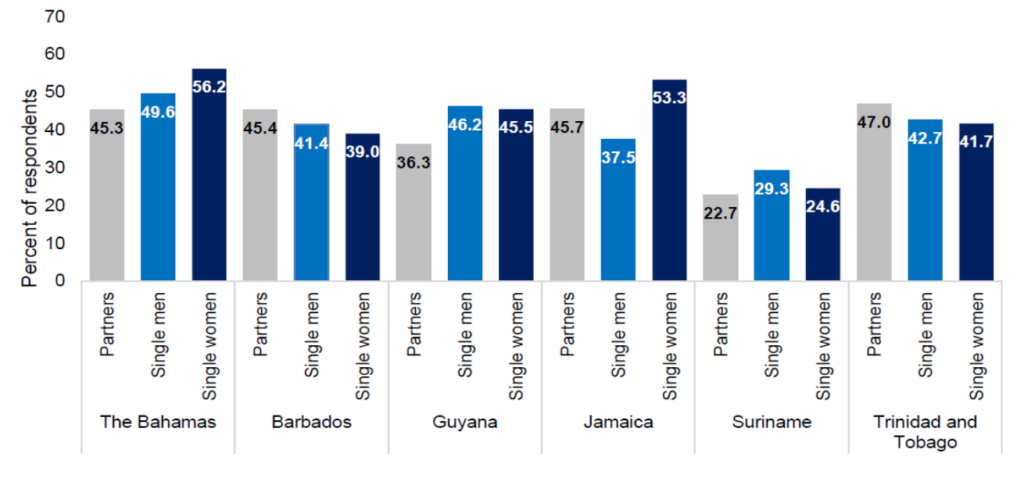

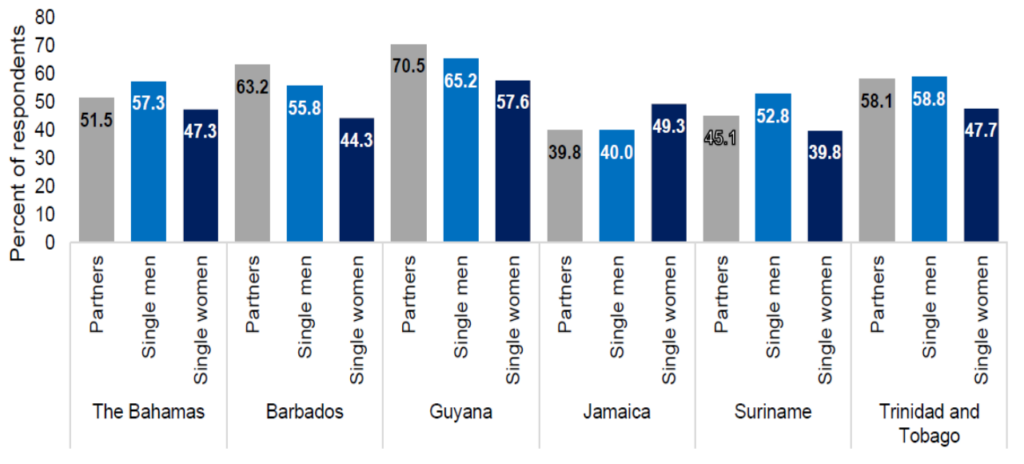

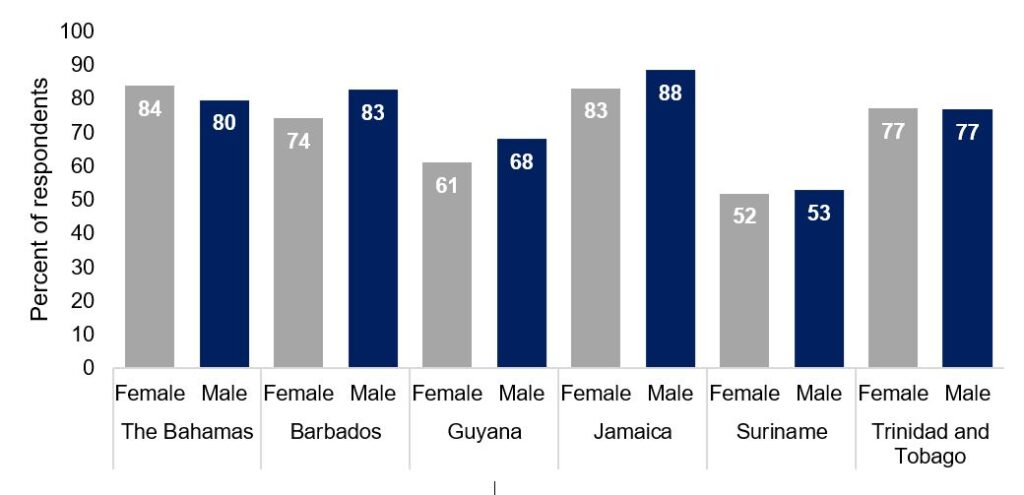

- The pandemic is worsening gender inequalities in the labor market. In most countries, more women have reported job losses than men (Figure 1). Whereas business closures were higher for men (Figure 2). Job losses amongst women were more prevalent in The Bahamas and Jamaica, whereas business closures amongst women were more prevalent in Jamaica and Guyana. These results, however, should be taken with care, as women are generally underrepresented in the labor market and more so as business owners.

Figure 1. Job losses by country and gender

Figure 2. Business closures by country and gender

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from IDB/Cornell Coronavirus Survey.

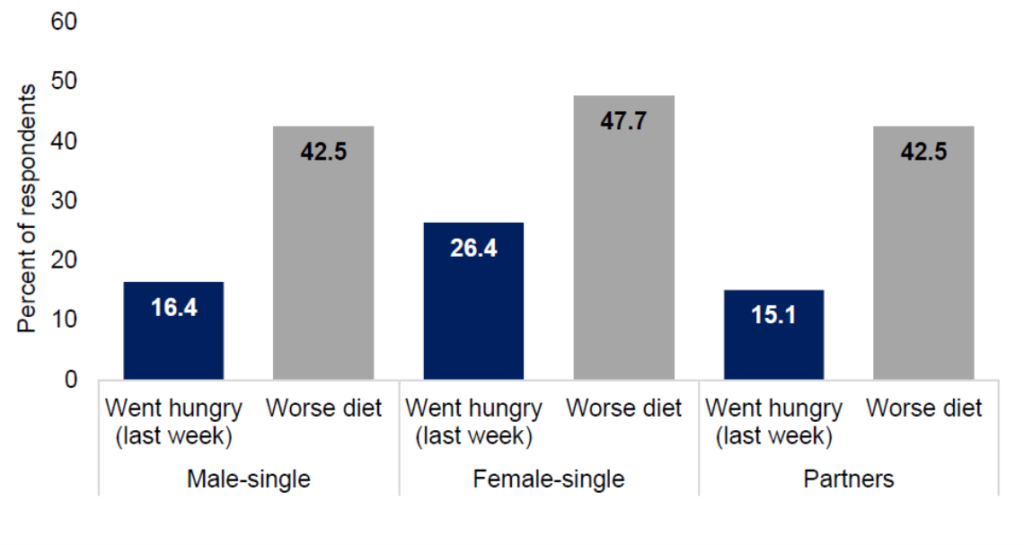

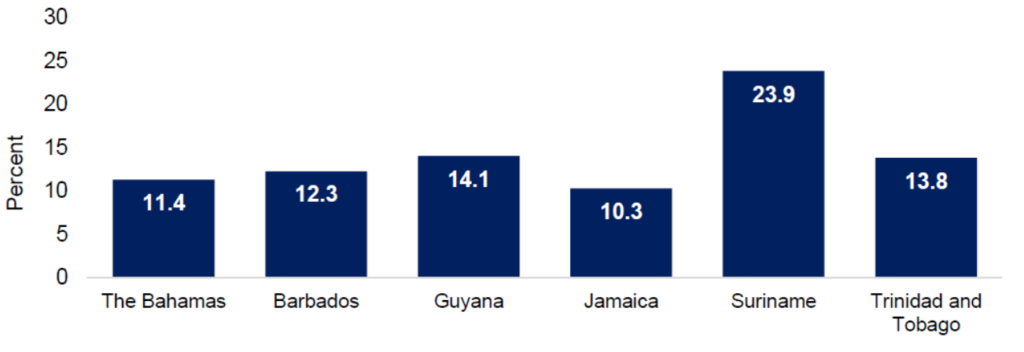

- The impact of COVID-19 on women and men’s quality of life has also been unequal. Some indicators relating to quality of life that we analyze are household’s perception of hunger, eating less healthy and the reported incidence of domestic violence. More single-headed female households reported going to bed hungry or eating less healthy than men. There was also a reported rise in domestic violence towards women, particularly amongst lower-income households and especially in Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago.

Figure 3. Percent of the population reporting changes in diet and food security by gender, C-6 average

Figure 4. Increase in the incidence of domestic violence by country

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from IDB/Cornell Coronavirus Survey.

- Gender disparities do not seem to be as large in terms of financial inclusion, but female headed households have lower financial resilience. The disparity between both genders in financial inclusion was not large (except for Barbados and Guyana), as measured by access to a bank account. The share of respondents from Suriname and Guyana with access to a bank account were amongst the lowest in the region. However, financial resilience seems lower for single females, which restricts their ability to withstand shocks. This likely constrains their ability to withstand hardship and increases the probability of being more gravely affected by the economic effects of the pandemic.

Figure 5. Access to a bank account by gender

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from IDB/Cornell Coronavirus Survey.

So, what can policymakers do with these results?

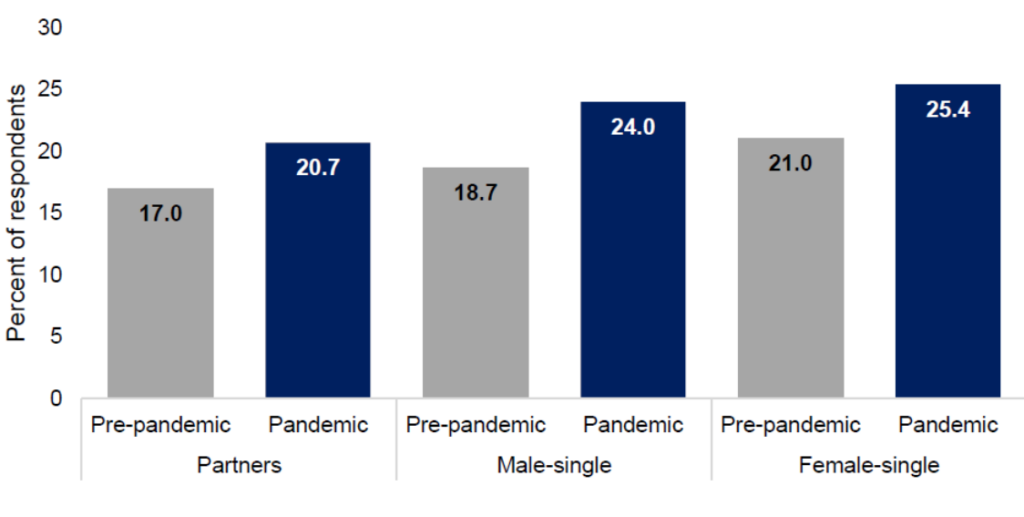

Countries responded promptly to the pandemic, rolling out a wide range of social protection measures since March 2020. This initial policy response provided support to all types of households; but it also meant that single-female households did not experience a greater increase in coverage (Figure 6). Although the reasons for this are likely complex and depend on a multitude of factors, it could be advisable to further review targeting by gender and household type, particularly given that single-female households are those we found to have the lowest level of financial resilience.

Figure 6. Coverage of social benefits by household type, average C-6 countries

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from IDB/Cornell Coronavirus Survey.

The implications of our findings thus encourage policymakers to continue responding to the pandemic. Yet refinement of the policy response in the context of the disproportionate impact of the pandemic across different groups in society would be advisable on a country-by-country basis. The results presented in this note should also be taken with care. Further work and data are needed, particularly at an individual level and capturing intra-household dynamics during the pandemic to inform policy makers going forward.

Leave a Reply