Two years have passed since COVID-19 first emerged, and efforts are underway to prevent the next pandemic from occurring again. While we are still learning the lessons of COVID-19, experts affirm this won’t be the last time a new or relatively rare infectious disease emerges. Indeed, the current monkeypox outbreak underscores this point. So, how are we going to prevent the next one? One answer is, in addition to enhancing our preparedness and response capacity for pandemics, through the conservation of nature.

A few weeks ago, the Inter-American Development Bank’s Natural Capital Lab within the Climate Change Division and Conservation International hosted the webinar “Infectious disease emergence and the destruction of nature: cautionary tales for Latin America” to showcase the latest discoveries from a recently published study by Conservation International and collaborators: The costs and benefits of primary prevention of zoonotic pandemics. This blog post aims to summarize the webinar’s main conclusions regarding the importance of nature-positive activities to prevent the emergence of infectious diseases and pandemics.

Where do zoonotic infectious diseases come from?

Emerging infectious diseases, including those caused by novel pathogens, have been on the rise for decades. Most of these diseases originate in animals, particularly wildlife, and then spill over into people. But why are they on the rise? The study by Conservation International and colleagues shows that there are three key elements to understanding this phenomenon:

- Deforestation and forest degradation: Clearing forests, particularly in the tropics and subtropics of the Americas, Africa, and Asia, allows displaced wildlife to interact with people and domestic animals, providing the opportunity for pathogens to jump species.

- The commercial wildlife trade: Moving and using wildlife, legally or illegally, through commercial channels enables spillover, especially under cramped conditions, where animals are stressed and are more vulnerable to infections. Experts believe that SARS and at least one monkeypox outbreak occurred under these circumstances.

- Poor infection control during animal husbandry: Industrial and non-industrial farms with poor infection control may produce pathogens that spill over from wildlife to other animal species and humans.

How do viruses spill over to humans?

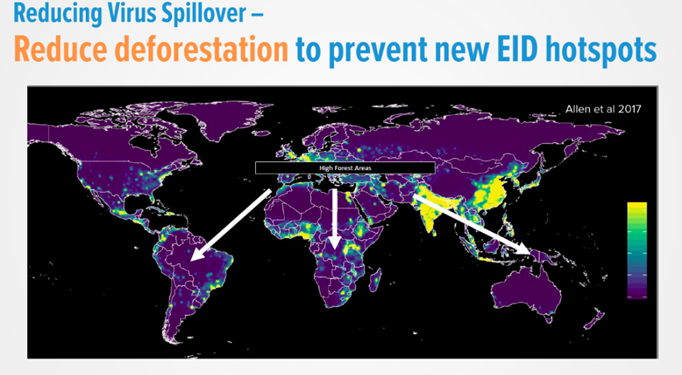

Virus spillover can occur when people are in contact with infected animals, alive or dead. There are places identified as emerging infectious disease hotspots (EID) where experts affirm that spillover risk is higher. Once spillover has occurred, and a human has the infection, an outbreak can follow if the virus can be spread from person-to-person, eventually transforming into an epidemic and then a pandemic.

How do we actually prevent pandemics from a nature conservation perspective?

Although the focus tends to be on preparing and responding to pandemics rather than preventing them, investing in prevention is a critical element for minimizing the threat of pandemics. The focus on preparedness and response means that we are underinvesting in an area that is key for saving lives and promoting health equity. Suppose that we also started investing in prevention. In that case, we can potentially avoid the cost effects of a pandemic, saving trillions of dollars. More importantly, it will save lives equitably, because the tools of preparedness and response (e.g., vaccines) tend to be more available to people in privileged positions.

Where and how should we use prevention funding?

There are a number of actions that governments, policymakers, institutions, and other actors could take related to nature conservation, including some projects the IDB is currently engaged in:

One of the first elements to prevent a pandemic is to stop deforestation and forest degradation in heavily forested tropical and subtropical areas. Spillovers are most likely to occur in places with a high human population, biodiversity, and deforestation. Areas with high biodiversity, such as tropical forests, often have a large abundance of different viruses. Of note, however, is that high biodiversity itself does not lead to outbreaks, epidemics, and pandemics. Rather, infectious disease emergence occurs when humans disrupt that biodiversity through the destruction of nature (e.g., deforestation), and this is one reason why deforestation leads to an increased risk of spillover.

This map shows the risk of emerging infectious disease events of animal origin around the world. Areas with higher risk tend to be located in the tropics or subtropics and have forests (or previously had forests) and high population density.

Poverty can be a driver of deforestation. While, on balance, greater wealth leads to greater deforestation, one action to help stop deforestation, forest degradation, and wildlife hunting and trade is to reduce poverty. The IDB is currently conducting a study to design a pilot conditional cash transfer program to reduce poverty and restore and conserve natural capital simultaneously.

Deforestation and forest degradation are also related to increased threats to Indigenous stewardship and autonomy over their lands. In the Amazon, the areas least likely to suffer from deforestation are areas managed by Indigenous peoples. The IDB’s Amazon Initiative has included specific targets dedicated to ensuring the prioritization of Indigenous peoples and local communities as beneficiaries.

Also, it is essential to enhance the health and economic security of communities living in areas of high deforestation to prevent spillovers and, therefore, pandemics. Strengthening local health systems is critical, and the IDB is currently designing and implementing health interventions based on multiple layer levels of care, where providing health services at the community level through community clinics is central as it constitutes the first level of care.

Likewise, it is essential to enhance the economic security of these communities. We need to develop training and capacity building programs to ensure that their people have the skills to take advantage of opportunities offered by the bioeconomy and the sustainable use of natural capital. This is one of our priority areas from the IDB’s Amazon Initiative and Natural Capital Lab program.

So, can nature conservation help prevent the next pandemic? The answer is “yes”, but it depends upon policymakers, academic institutions, multilateral development banks, and civil society organizations working together to include pandemic prevention alongside plans to prepare and respond to pandemics. We need to pursue policies that prioritize upstream pandemic prevention through nature conservation. Seeing nature and communities as critical for tackling pandemics can help us prevent the next pandemic—conservation is an issue of public health.

Do you want to learn more about nature and infectious diseases?

Read more here:

Ecology and economics for pandemic prevention

Leave a Reply