When world trade consisted mostly of final goods or inputs used only in goods for domestic final demand, the relationship between trade agreements and trade flows was relatively simple: sign an agreement with another country and the trade flows between the two nations would most likely increase, end of story. With the emergence of global value chains, however, the story is not so simple. Because inputs are increasingly used in the production of goods that are exported to other countries, the flow of intermediate inputs between two nations is not only influenced by the extent to which they are integrated with each other but also by the extent to which the country using the inputs is integrated with third markets.

It’s rather like when your favorite airline allows you to use miles from a second airline to buy tickets. How often you would fly with the second airline would depend not only on whether you can use your miles to buy tickets with that airline but also whether those miles are recognized by your preferred airline. If this weren’t the case, you wouldn’t fly with the second airline all that frequently.

The fundamental problem with the integration process in Latin America has been its level of “fragmentation,” that is, the co-existence of several different trade agreements with limited membership scope. This tends to encourage production linkages between members of agreements but not across agreements because rules of origins generally limit the amount of inputs that can be used from outside the respective blocs. Faced with this reality, we want to know how the region’s flow of intermediate inputs would be impacted if this fragmentation of Latin America’s regional integration process were reduced?

We employ an empirical trade model, the so-called gravity equation, to answer this question. The variable of interest in the model is the value-added from, say, Colombia, that is embodied in the exports of, say, Chile. This variable is particularly useful for analyzing the effects of trade agreements on the formation of supply chains for two reasons. First, it captures the flows of value-added from one country that are used in the production of goods in another. It therefore provides a realistic measure of supply chains between two nations. Second, the input imported from abroad is used in the production of a good that is subsequently exported. Accordingly, this variable is likely to be influenced not only by any agreement that the importing country may have with its sourcing partner but also by any agreement that it may have with countries to which the good embodying this foreign input will be exported. This, in fact, underlines the essence of the estimation: the development of supply chains between two countries is likely to be influenced not only by the extent to which these two countries are integrated but also by the extent to which the country using the foreign inputs is preferentially integrated with third markets. Details of the estimation can be found in a recent IDB publication, Connecting the Dots.

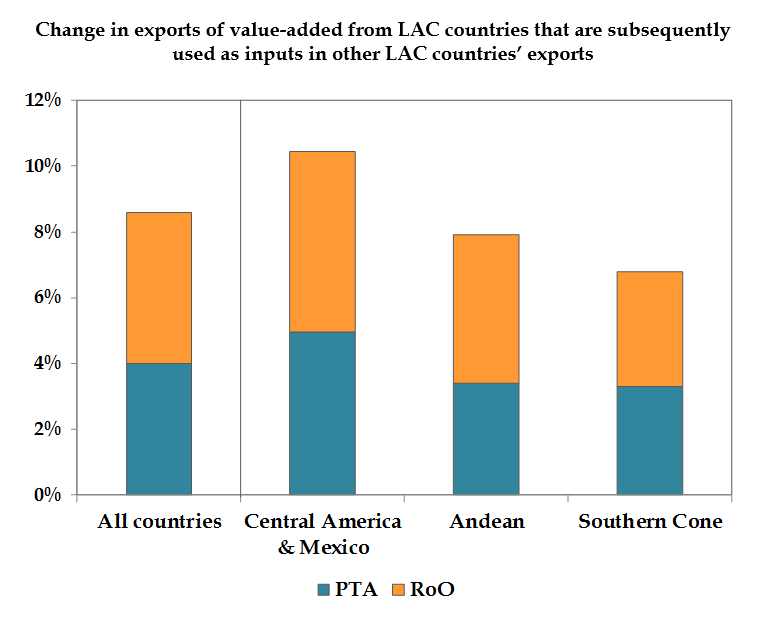

The main results are summarized in the figure below. The first column shows the average value-added across all source countries and destinations in Latin America. PTA measures the increase in value-added that arises from sharing a trade agreement, and RoO measures the increase in value-added that arises from sharing the same set of rules of origin. The results, shown in the first column, point to an average increase in value-added of around 9 percent. That is, for the average country in Latin America, exports of intermediate goods that are subsequently used as inputs in other countries’ exports increase by 9 percent, with equal contributions from the PTA and RoO effects.

The rest of the columns show the results when the sources of value-added (that is, the exporting countries) are grouped by subregion. The second column presents the average for Central America and Mexico when they export intermediate goods that are used as inputs in the exports of other LAC countries. The third and fourth columns do the same for the Andean and the Southern Cone countries, respectively.[1] The results indicate the existence of some heterogeneity across subregions, with the countries in the Central America/Mexico region exhibiting slightly larger average effects. Another finding, not shown in the figure, is that the largest impacts appear in the formation of supply chains across subregions, which arises from the fact that there is more room for integration across subregions than within them.

Overall, the results suggest that the move toward convergence and, eventually, a regionwide FTA might have significative and positive impacts on the formation of regional supply chains within Latin America. Reducing the fragmentation of Latin America’s integration process can boost the international fragmentation of production across the region.

[1] Central America/Mexico includes: Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua and Panama. The Andean countries includes Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela. The Southern Cone includes Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay.

Leave a Reply