Why do companies like the Brazilian aeronautics giant Embraer, the Mexican building materials company CEMEX, or German vehicle manufacturer Volkswagen invest abroad?

One of the main reasons is that they are seeking larger markets for their products, not only in the country where they are investing but also in neighboring countries or those it has trade agreements with. For example, Embraer has set up sales offices in the US and Portugal to make the most of NAFTA trade preferences and the EU single market, respectively.

This type of investment is called an export platform because it helps firms move beyond trade barriers like tariffs and get physically closer to their target market, thus reducing logistics and transportation costs.

This can also happen in the service sector. US-based companies, for instance, sometimes opt to offshore their customer service operations and set up call centers or administrative offices in Central America or the Caribbean, to bring down costs and provide a service that is culturally compatible with their clients while still within US time zones.

The second reason to invest abroad is to increase efficiency. Companies invest in different locations so that each product can be manufactured wherever it is most cost-effective to do so. This type of strategy is known as vertical investment. Volkswagen’s headquarters are in Germany, but it produces and assembles cars in different parts of the world to cut costs. For example, it has access to the entire North American market via NAFTA from its assembly plants in the Mexican states of Puebla and Tlaxcala. Volkswagen exports 55 percent of the cars it produces in Mexico to Canada or the US, while 17 percent go to the Mexican market, according to the Mexican Automotive Industry Association (link in Spanish). This investment is part of a hybrid strategy that combines the notion of an export platform with the quest for greater efficiency.

Another slightly different example of hybrid investment is Mexican multilateral CEMEX’s investments abroad via mergers and acquisitions in the Dominican Republic Egypt, the Philippines, Panama, Spain, and the US. The company has benefited on two counts: first, demand for cement in these markets is high so this strategy has brought down CEMEX’s trade costs; and second, it has also learned about local demand patterns and other specific features of the new markets from the companies it has acquired. At the same time, whenever the companies it purchased lacked efficiency, CEMEX reproduced aspects of its own business culture and transferred the necessary technology and skills to improve their performance.

How do companies that invest abroad impact development?

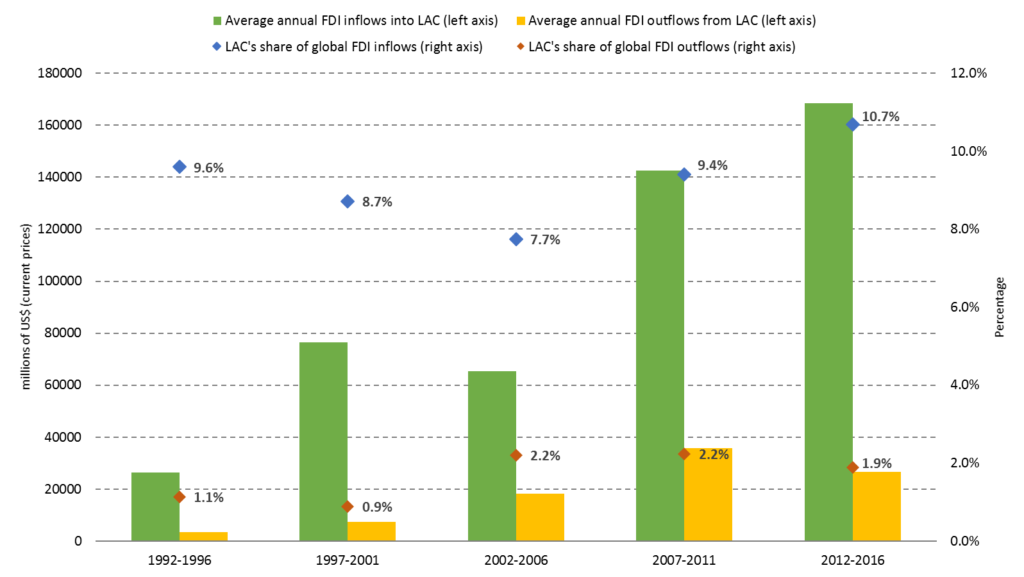

Global foreign direct investment (FDI) flows reached an average of US$1.6 trillion in recent years (UNCTAD). In Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), FDI inflows and outflows remain on the rise. Figure 1 shows that FDI flows to the region have increased over the last 20 years and that today they stand at US$170 billion, or 11% of the global total. Figure 1 also reveals that although FDI from LAC companies has increased eightfold compared to 20 years ago, it still only represents 2% of global foreign investment.

Figure 1. FDI flows in LAC and their share of global FDI flows by five-year period

FDI is about much more than financial flows, however. It can have much deeper impacts on the recipient countries’ development.

Generally speaking, FDI creates jobs, more jobs than those that are eventually lost due to the shrinking or closure of local firms that cannot compete with the newly arrived firms from abroad. It is not just the quantity of these jobs but also, frequently, their quality that prompts governments to seek to attract FDI.

The relative complexity of the tasks or processes involved in their operations means that multinational corporations (MNCs) employ a larger share of skilled workers. They also increase demand for related services that often need relatively higher-skilled workers (such as transportation services, for example). In some cases, FDI can even create jobs in places where unemployment rates are high. Furthermore, MNCs pay wages that are 40 percent higher, on average, than those of local firms.

FDI can also have negative effects on labor markets. For example, an MNC sets up operations in a given country and starts producing goods or services more efficiently than local companies. When consumers realize that the MNC’s products are cheaper and of better quality, they choose them over those produced by local companies. This may reduce local firms’ turnover, causing them to lower employee wages or even shut down.

However, FDI can increase demand for local inputs and lead to the growth of industrial clusters where synergies emerge between MNCs and local firms, creating jobs, as is the case in the Puebla–Tlaxcala automotive cluster in Mexico, which grew around Volkswagen.

Through this trade in inputs, even within production clusters, countries can develop local industries or firms that specialize in producing certain intermediate goods without the need for the country to be competitive along the entire length of the production chain for the final product. Local companies from these countries can thus participate in global or regional value chains (link in Spanish). In other words, they can become part of the international production process in which a final good is made up of intermediate goods that are each produced in the country where the quality/price ratio is highest. This increases the productivity of these companies, which can offer relatively better labor conditions than the average local firm does.

Consequently, countries that receive FDI also benefit because the productivity of MNCs is estimated to be between 15 percent and 60 percent higher than that of local firms due to demonstration effects and labor mobility, and also because of increases in the quantity and quality of intermediate inputs that circulate in the local economy.

In sum, FDI has the potential to create win-win situations for both the investing company and the country receiving the investment.

If you would like to find out more about FDI and hear some of the region’s success stories, join the IDB’s free, online course Foreign Direct Investment As a Driver for Development in Latin America and the Caribbean (course in Spanish).

Unless national governments provide the incentives companies get abroad, they will continue to invest.