Many predictions have floated about the future of global value chains (GVC), or the separation of production in stages across borders, in a post-COVID19 world. They include some degree of reshoring by which global lead firms bring back to their home country the production of intermediate inputs initially offshored to other countries. Other predictions include a higher degree of nearshoring in which intermediate inputs are produced in nearby countries.

Certainly, COVID-19 has hit hard the core principle of “just-in-time” inventory management, as the shutdown in the production of a supplier has meant an almost simultaneous closure of the establishments located downstream, where products get produced and distributed.

But international trade associated with GVCs, which mostly consists of intermediate inputs, was also hit hard during the Great Recession of 2008, and the structure of GVCs did not fundamentally change at that time. GVC-trade fell sharply only to grow back mostly within the same existing production networks, the so-called adjustments along the intensive margin. The extent and the configuration of the prevailing GVC networks, the extensive margin, did not drastically change. The main reason is that it takes years and much trust to build these networks among companies, and once such relationships are formed, they tend to be “sticky.”

COVID-19 is undoubtedly responsible for massive disruptions in many GVCs like in the auto industry, and therefore some changes could occur this time. While it is difficult to fully cover for global shocks like a pandemic, lead firms may seek a more diversified supplier base that can be useful, especially for regional shocks.

This supplier diversity might open up some opportunities for suppliers in Latin America and the Caribbean. But even this strategy has its own limits. Coordinating multiple suppliers can be a costly proposition for many lead firms. Furthermore, if multi-sourcing means spreading the production of intermediate inputs too thinly across several suppliers, each one of them might not produce enough volume to break even, especially in sectors with large scale economies, like cars.

These limitations do not imply that GVCs will remain intact when COVID-19 is behind us. After all, some GVC changes that benefit our region were already underway even before the pandemic. But without extensive reforms in its trade and investment environment, Latin America might not substantially increase its GVC participation only as a result of COVID-19. Certainly, there is a momentum to build on, but Latin America must do its homework in reducing its prevailing trade and transport costs. From trade policy to trade and investment facilitation and transport infrastructure, such as modern airports, border crossings, ports, highways, the list of factors that influence a firm’s integration in GVCs is well known.

Trade and climate change

However, one aspect that has not received enough attention regarding GVC participation is the role of environmental issues.

The relationship between trade and climate change has several dimensions, from the emission of greenhouse gases associated with the production and transportation of goods that are traded across borders, to climate change policies that might affect the intensity and the composition of trade flows.

Indeed, there is a natural tension concerning trade and environmental policies. On the one hand, the increasing environmental requirements imposed by industrial countries are sometimes seen as unilateral protectionist actions that could increase production costs and, thus, harm the competitiveness of Latin American exports. On the other hand, these requirements might be viewed as an opportunity to innovate and differentiate production, allowing firms to enter more competitive supply chains (or move along more profitable stages), resulting in potentially higher export prices and profits while improving energy efficiency.

The rest of this blogpost argues that this second view, the so-call “positive agenda” between trade and climate change, will be critical if the region wants to foster its participation in GVCs.

Environmental requirements

Because global lead firms have a brand name to protect, they closely monitor that their suppliers comply with certain standards (e.g., quality, labor, environmental). In many countries, governments and consumers have become more conscious of green approaches to producing goods. Global lead firms, concerned about their reputation, are eager to improve the sustainability of production, thus requiring suppliers to conform to environmental standards.

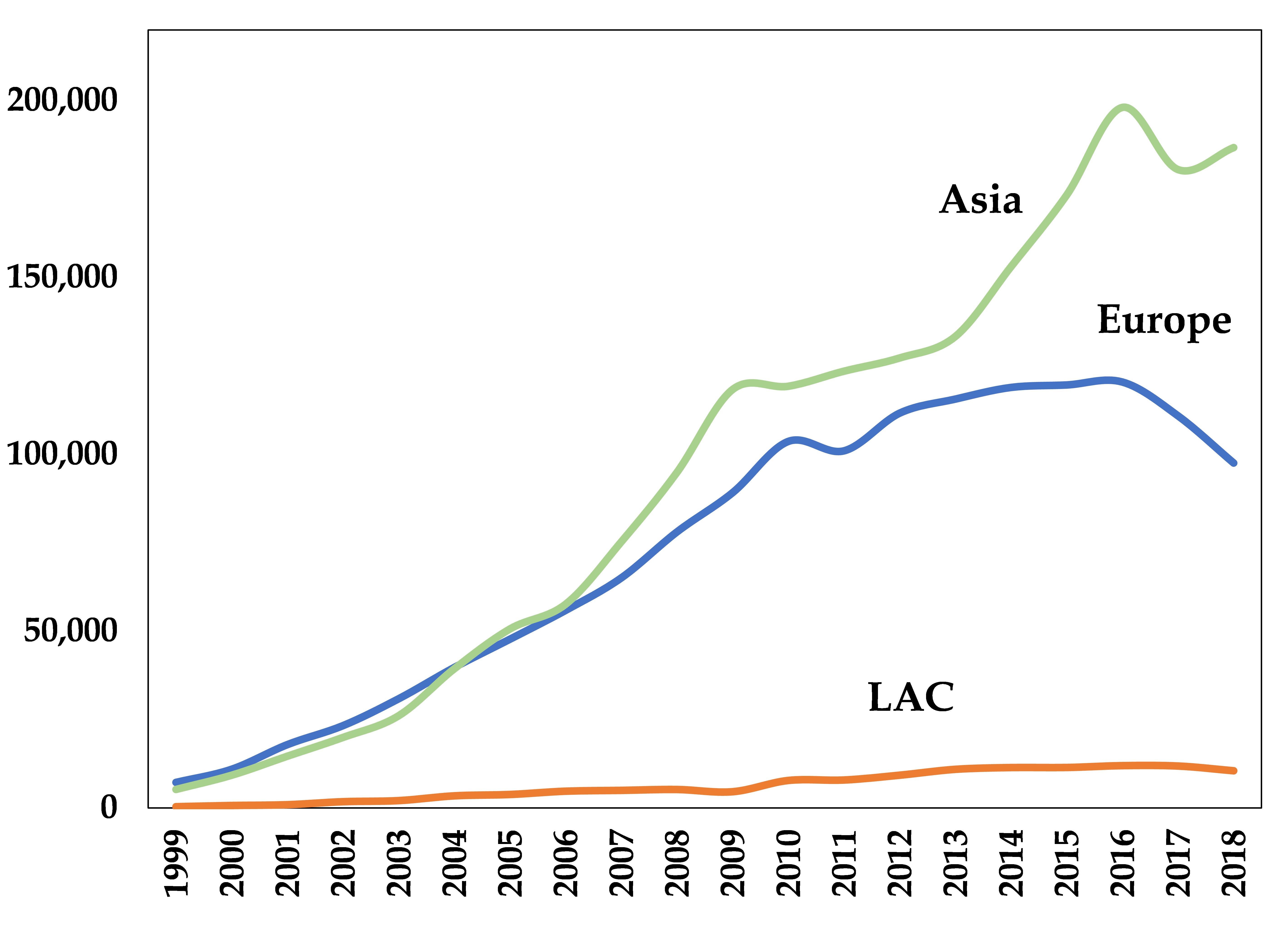

How necessary are environmental requirements for GVC participation? At the IDB, we study the evolution of certain environmental standards in countries with a large presence in GVCs. For instance, Figure 1 shows the number of ISO 14001 certifications granted to businesses in Europe, Asia, and Latin America for comparison purposes.

Figure 1: Number of ISO 14001 certifications

Source: IDB with data from ISO Surveys

The ISO 14001 is a voluntary standard to reduce environmental footprints through a management system. Similar to the ISO 9000 on quality control, the ISO 14001 can be applied to any business or sector. It was developed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and has been implemented in more than 170 countries.

Figure 1 shows the important increase of ISO 14001 certifications in Asia and Europe during the last two decades. Clearly, not all these certifications are related to firms inserted in GVCs. Still the trend is consistent with abundant anecdotal evidence indicating that many corporations in the world require their supplier to comply with ISO 14001 certifications, including IBM, Xerox, Honda, Toyota, Ford, GM, Bristol-Myers Squibb or Quebec Hydro.

ISO 14001 is just one of many environmental standards and regulations. Moving forward, the question is, how prominent environmental issues are likely to be for GVC insertion? Global lead firms are becoming more conscious about the environment, and COVID-19 will likely draw even more attention to climate change. Why? Because scientists predict that climate change can contribute to more pandemics.

The IDB is currently working to improve our understanding of the environmental issues related to GVC participation and its implications for Latin America and the Caribbean. The region needs to continue pushing its trade and integration agenda by addressing the well-known challenges associated with GVC integration while also paying attention to new issues, such as those related to climate change.

Leave a Reply