The international game of hopscotch

Policymakers worldwide try to boost economic growth and investment, including by attracting foreign direct investment (FDI). For this purpose, they revise investment laws, reduce administrative burdens, propose new investment incentives schemes, and create and reinvent the agencies charged with promoting and facilitating investment – investment promotion agencies (IPAs).

Wishing to improve their IPAs, governments keep on changing their institutional design. Every year a new agency is opened, reformed or closed, often to be reopened soon after.

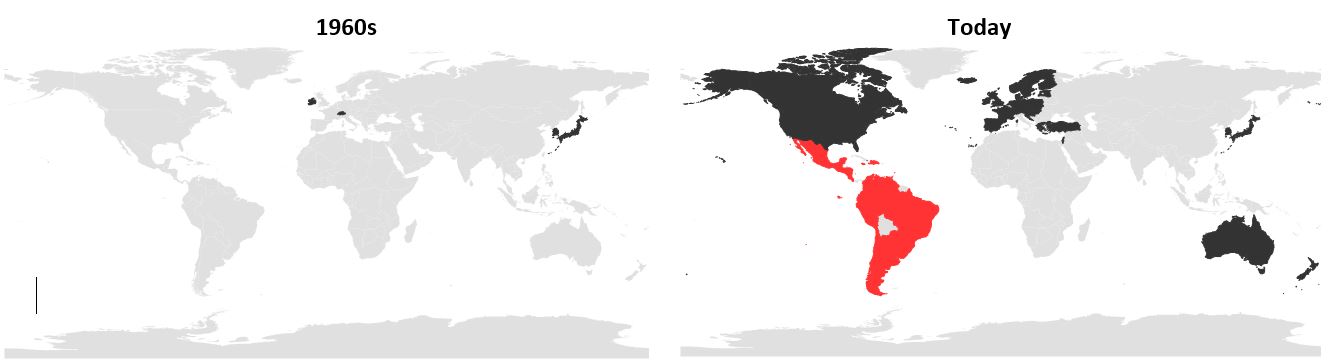

The number of countries with IPAs quadrupled over the last 30 years in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and close to one in five underwent a major institutional reform in the past five years. A new agency was created in Argentina, Chile and the United Kingdom[1] in 2016 alone.

Figure 1. The Worldwide Diffusion of Investment Promotion Agencies

Source: Volpe Martincus and Sztajerowska (2019)

They have also significantly increased the reach of their international networks: nearly 20 new offices were opened abroad in the last five years (Figure 2). This continuous tinkering with the design and responsibilities of such agencies shows that governments are clearly in search of solutions, and the task is far from complete.

Figure 2. The Spread of IPAs’ and the Network of their Overseas Offices Worldwide

Note: LAC countries are colored red and non-LAC OECD countries are colored in black.

Source: Volpe Martincus and Sztajerowska (2019)

Do all roads lead to Rome?

What have we learned about the experience of such agencies in over 50 countries? One thing is clear, there is no magic solution for running effective agencies.

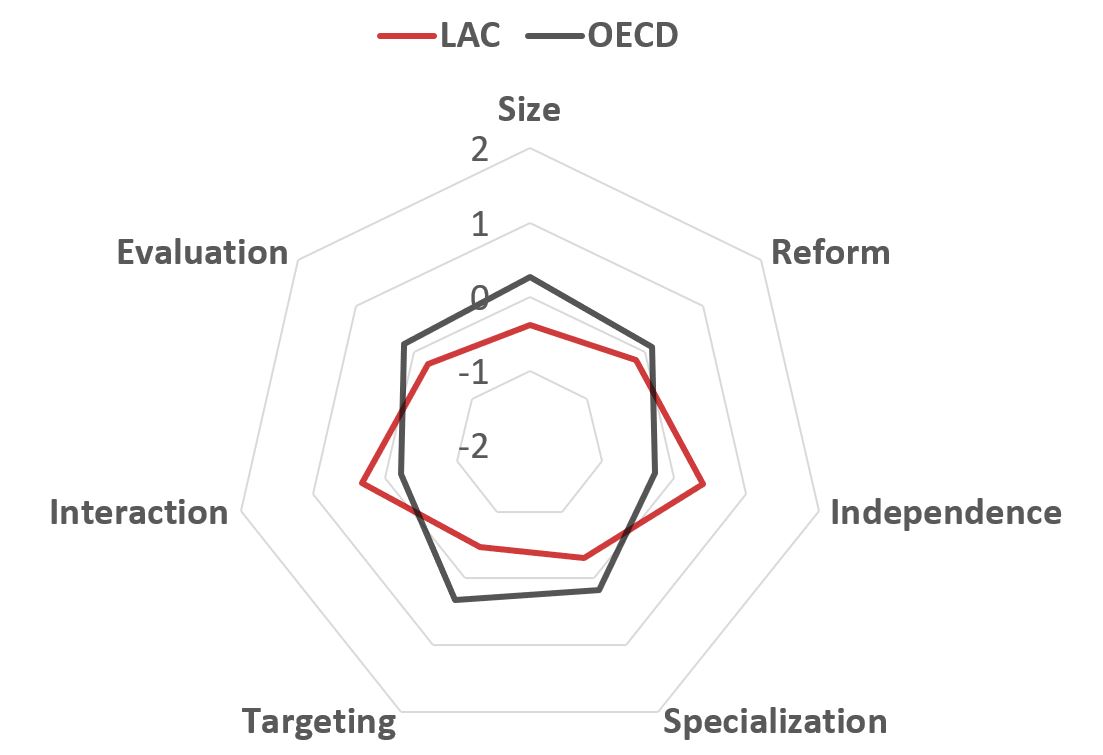

How to Solve the Investment Promotion Puzzle, a complete and innovative survey of 51 governments and their agencies in LAC and OECD reveals there are multitude of approaches to setting up and running an IPA. Agencies differ in nearly all aspects, ranging from overall size, reform intensity, institutional independence, as well as the degree to which they specialize, target investments, interact with others and evaluate their activities (Figure 3).

Overall, IPAs in OECD countries tend to be larger, more specialized and targeted, and evaluation-oriented than LAC agencies. For example, LAC agencies have a median annual budget of US$5 million, compared to US$14 million for OECD countries. The median IPA also employs a total of 48 staff, compared to 135 in OECD (30%-40% being devoted to FDI attraction).

Figure 3. The Overall IPA Scorecard

Note: The report includes scorecards for each individual IPA relative to the OECD and LAC averages. In addition, the online tool www.iadb.org/InvestmentPromotion allows for comparisons across agencies.

Source: Volpe Martincus and Sztajerowska (2019)

In turn, LAC agencies tend to be more independent and interact with a larger number of actors, partially to offset their small size and other weaknesses of the public administration. For example, one-third of LAC IPAs are private or joint public-private, and most have a Board of Directors with nearly two-thirds of non-public members. A median LAC agency also interacts with 30 different stakeholders from both the private and public spectrum, compared to 26 such actors for a median OECD agency.

Key lessons: What affects impact?

As governments worldwide play hopscotch of investment promotion, constantly changing the constellation of their IPAs and their characteristics, do investment promotion agencies make a difference?

The short answer is yes – on aggregate.

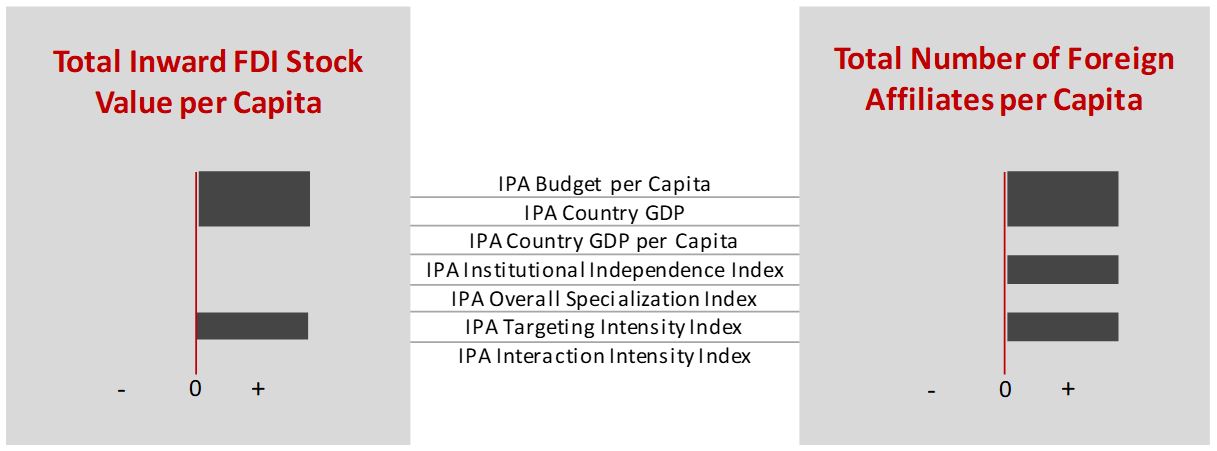

All the same, IPAs’ relative size and specific strategies matter for their effectiveness. For example, controlling for their countries’ size, the study finds a positive relationship between IPAs’ budget (per capita) and targeting intensity and inward FDI both in terms of total stock value (per capita) and the total number of affiliates of multinational firms established in the country (per capita). (Figure 4)

Policymakers and IPA experts searching for a roadmap as to what truly requires reform and what should remain unchanged should conduct impact evaluations of individual agencies. In that spirit, the IDB’s Trade and Integration Sector is currently developing such evaluations for 12 agencies in LAC and the OECD is in conversations with several of its agencies.

Figure 4. Investment Promotion Agencies and Impact on FDI

Note: The figure shows the estimated effects of country-level and investment promotion agency-specific factors on the respective country’s total value of inward FDI stock per capita and the total number of affiliates of foreign multinational firms established in the country per capita (expressed in natural logarithms) if statistically significant. Further information on the methodology can be found in the report.

Source: Volpe Martincus and Sztajerowska (2019)

Leaders who truly want to resolve the investment promotion puzzle ought to invest their intellectual and political courage by admitting what’s lacking and undertaking evidence-based policies.

Otherwise, the hopscotch game will continue without end.

The main findings of this report can be visualized in these interactive figures.

[1] In case of the United Kingdom, a previous agency – UKTI – was restructure and absorbed into the Department for International Trade.

Leave a Reply