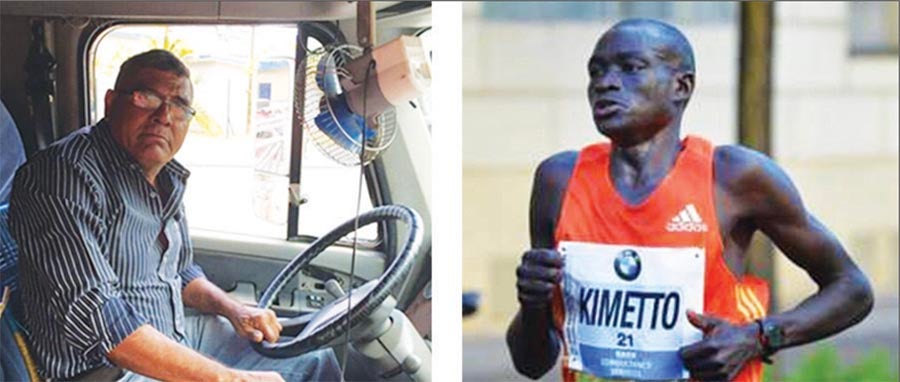

Don Heriberto Martinez, a 55-year-old truck driver from El Salvador, spent most of his adult life transporting goods down the Pacific corridor. The corridor is the shortest route between Mexico and Panama, where six billion dollars of commercial goods are transported every year. Martinez usually spends eight days to drive its 3,200 kilometers. On the other hand, Dennis Kimetto is a 32-year-old Kenyan athlete who holds the marathon world record. He can run about 20 kilometers per hour. In a hypothetical competition down the Pacific corridor, who would arrive first: Kimetto, on foot, or Martinez, by a truck?

The right answer is Kimetto, who at 20 kilometers per hour would be able to finish the trip in 6.5 days. Of course, this is merely a hypothetical race as it doesn’t take into account eating or resting. But it does highlight Martinez’s trip inefficiencies. He spends at least 6 days at the many border crossings, waiting to clear customs, hoping that his 20 tons of feedstock won’t perish along the way.

And what can we learn about logistics and connectivity to consolidate Latin America and the Caribbean’s participation in global value chains?

When I met Martinez in the border between Costa Rica and Nicaragua, he had been waiting five days for the lab results of a rice cargo to come back from San José, where they had been sent for chemical residue testing. When he finally arrived at his destination, he drove at an average of 16 kilometers per hour – a full 20% slower than Kimetto.

Needless to say, every additional hour has a great impact, not only on his particular freight but also on trade in general. Consumers end up paying more, and the region as a whole is less competitive. The transportation costs in Latin America and the Caribbean are between two and four times higher than in OECD countries. For large manufacturing firms, the costs of transportation and clearing customs in Central America can represent more than one-third of the final cost. But for small companies, these expenses are even higher – more than double of the final cost.

Reducing these logistic costs is crucial for Latin American and Caribbean countries to take advantage of global value chains and successfully join the international economy.

A lot, in that respect, has been done already. The IDB, for example, has modernized about 400 kilometers of the Pacific corridor, investing a total of 1.5 billion dollars. Investments have also been made in modernizing ports and airports. The expansion of the Panama Canal is bound to have a positive impact on trade flows and logistics. Less visible, but equally important, are the improvements on trade software: the harmonization of laws and regulations, and streamlining of processes to facilitate trade. In 2011, for instance, Martinez’s company had to submit dozens of import papers and sanitary licenses, in writing, to multiple government agencies. After that, Martinez had to wait many weeks before he could actually start his journey. Today, however, through the implementation of the Trade Single Window program in El Salvador and Costa Rica, Martinez’s company can submit much of the required documentation electronically, in advance. This helps cut time and costs prior to his departure.

So why does he still spend five days at the border? Because the rice-cargo sanitary permits are not part of the Single Window yet.

Countries that improve border infrastructure and simplify their customs procedures simultaneously boost their trade by double rather than improving them separately. It is important to underscore this point because more trade means more jobs, more revenue and ultimately economic development. Physical infrastructure consumes about 70% of the resources devoted to modernizing border crossings, but it is responsible for only one-fourth of time delays. On the other hand, processes cause three-fourths of delays and don’t require as big financial investments. The combination of hardware and software, indeed, requires a very important partnership between technology and connectivity.

We recently visited a Logistics Control Tower in Silicon Valley. It is a private information hub that provides real-time data on the physical location of containers, in and across countries. It improves planning and problem-solving, at the trading company level. Now imagine if we could have a logistics control tower, for example, in the processed-food value chain, which relies on glass containers for their products. In Central America, you may get glass bottles from Mexico, Costa Rica or China via the Panama Canal. A Logistics Control Tower in Panama, for example, would inform, in real time, if there is a problem with the containers in the Canal, or in the border crossings in Costa Rica. The trading company could immediately decide to source the glass from Mexico, for instance, to avoid delays and keep costs under control. Additionally, Martinez’s truck and containers could be equipped with tracking technologies that send data to a central information hub. Border crossings would be interconnected, and Customs officials would also know in advance what is in the truck, whether it has the required sanitary permits, licenses, fees, and so on. Data would be available for private and public stakeholders to facilitate logistic planning and problem-solving.

Technology, modern hardware and streamlined processes – overlaid with high connectivity – hold the largest potential for improving trade and reducing logistic costs.

They can help us break gridlocks in border crossings. Martinez would be able to drive at 60 kilometers per hour and arrive in 2 days instead of 8. He would not only transport vegetables from country to country; he would, in fact, be part of a larger regional value chain.

Technology is already here. We need to take full advantage of it and make the region a real player in global trade.

Leave a Reply