Despite a troubling persistence of racial gaps in labor market outcomes over the last 15 years in Latin America, the role played by discrimination has not received much attention. We know surprisingly little about hiring bias against Afro-descendants in the region. A recently released study contributes to a large pool of evidence about racial bias against Afro-descendants by employers in high income countries.

There are some important studies for Brazil but less so for the rest of the region. For example, a recent study in Brazil found that employer preferences for white workers explain approximately 7% of the racial wage gap. Another study, using data from Brazilian firms in the formal sector, finds strong patterns of co-racial hiring. New firms that are disproportionately comprised of white employees will initially tend to hire white workers, although with persistent growth the hiring becomes more diverse.

Broadly speaking, the studies in this literature can be mapped to the three key actors in Becker’s model of discrimination in labor markets – employers, co-workers and customers. Our new working paper extends beyond these traditional spheres to explore racial bias in labor market intermediation services – in other words, in job counseling and referral services.

First-hand information about racial bias in the labor market

While there is an emerging literature that uses vignettes and/or laboratory type experiments to measure bias against different groups, nothing compares to the opportunity to directly observe and interact with front-line workers.

In Colombia, the employment agencies known as the Cajas de Compensación Familiar (CCFs) are recognized as providers of high-quality labor intermediation services, as part of the larger Public Employment Services (PES).

Both the CCFs and the PES are committed to eliminating bias against diverse groups in their services and have implemented a set of policies to improve the skills and awareness of job counselors. Their collaboration in the research study was not an academic exercise but rather an opportunity to explore how to improve service delivery. The Navarra Center for International Development and Econometria also collaborated in the study.

Real CVs, real job posts, and real job counselors

Working with real CVs, real job posts, and real job counselors within the public labor market intermediation service in Colombia, we document three different types of racial discrimination.

- Explicit: bias willingly acknowledged to others

- De facto: bias revealed by what people do

- Implicit: unconscious bias revealed through the implicit association test

Perhaps not surprisingly, we found that job counselors do not freely express to an interviewer discomfort with the scenario of having Afro-descendant neighbors or a preference for working with a non-Afro-descendant worker. However, in their day-to-day job responsibilities of matching talent to job opening, the job counselors were 15% less likely to refer black candidates than white candidates.

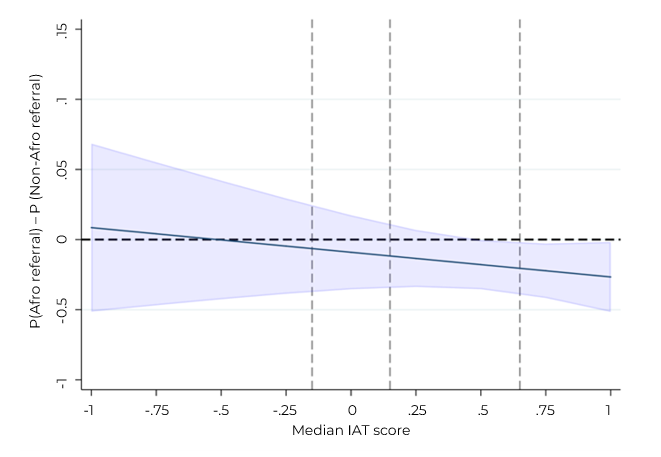

Moreover, using an Implicit Association Test (IAT), we measured a high level of implicit bias, finding that 2/3 of job counselors revealed unconscious preferences for whites over Afro-descendants. While this does not suggest a higher level of racial bias than elsewhere, according to a global study these results are average for Colombia which is in the mid-point of the 146 countries. The implicit bias of the counselors is related to their work responsibilities. We found that when the median IAT score within a job center increases (meaning a higher implicit bias against Afro-descendants at that center), the probability of forwarding an Afro-descendant CV decreases with respect to a non-Afro-descendant CV (see figure below). The correlation of the unconscious bias with the referral rates suggests that racial bias in intermediation services may be an important contributor to racial gaps in the labor market.

Differential probability to refer an Afro-descendant CV vs. anon-Afro-descendant CV by the median IAT score of job center.

There were other important findings. Afro-descendant counselors, albeit a much smaller sample, did not exhibit the same bias towards whites, which implies that efforts to have a more diverse staff can change referral rates across centers. Counselors with more experience and education were less likely to be biased, suggesting that training may be paying off. Based on these initial results, a new phase of collaboration will explore interventions to reduce bias in the decision-making process.

Only by understanding the bias and rigorously evaluating the impacts of strategies and interventions, can we learn how to advance at chipping away some of the most persistent gaps in the region.

Leave a Reply