From a certain optic, advances in education in Latin America and the Caribbean have been remarkable. In 1900, only one in three children attended primary school. Very few advanced to secondary school. Today, primary education in the region is nearly universal and enrollment in secondary school stands at nearly 80%.

Unfortunately, those gains in access to education have not been accompanied by progress in educational quality. On the contrary, the differences in academic achievement in the region and the developed world are stark and threaten to undermine the region’s aspirations for productivity, growth and poverty reduction.

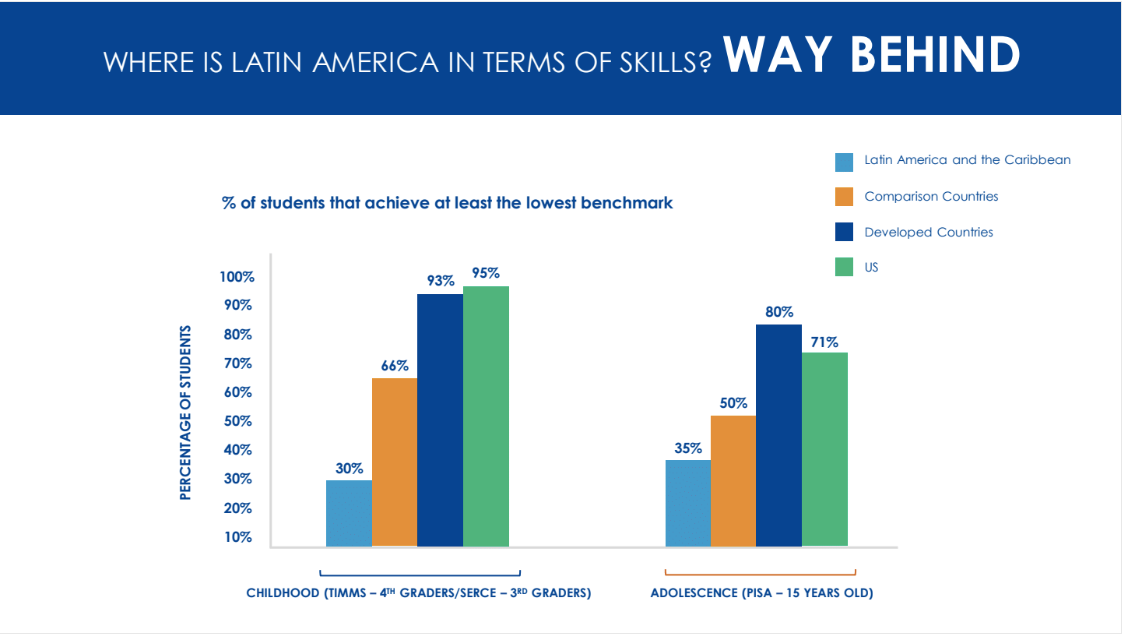

Most countries in the region have participated in international and regional assessments that allow for comparisons of academic skills levels. In our recent flagship report Learning Better: Public Policy for Skills Development, we equated scores from the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMMS), a global assessment of fourth graders, taken in the region only by Colombia and El Salvador, and the Second Regional Comparative and Explanatory Study (SERCE), a regional assessment administered to third-graders in 15 Latin American and Caribbean countries. We found that fewer than half of the students would have scored above the minimum standard had they participated in TIMMS. That is to say they may have some very basic mathematical knowledge. But they cannot add and subtract whole numbers, recognize parallel or perpendicular lines and familiar geometric shapes, or coordinate maps, and they cannot read and complete simple bar graphs and tables. By contrast, 95% of fourth grade students in the United States and 66% in countries with similar levels of gross enrollment and development achieved that minimum standard.

The lack of basic academic skills during childhood sets the stage for poor skills development in adolescence and is compounded by the low quality of secondary education in the region. In 2015, 10 Latin American countries participated in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). Amongst the 72 participating economies, all Latin American and Caribbean countries ranked at the bottom of the proficiency distribution: Chile, Latin America’s best PISA performer, ranked 48 in math, 42 in reading, and 44 in science, while the Dominican Republic was the worst performing country. Moreover, more than 63 percent of the 15-year-old Latin Americans that participated in PISA were unable to conduct more than the simplest math tasks for that grade and are likely to struggle using basic math concepts throughout their lives.

Results from the 2013 Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate (CSEC), an assessment administered to secondary students in four Caribbean countries, show similarly poor results for Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, and Guyana. CSEC, a test taken by people who have finished the five years of secondary school, is used to determine access to higher education. Only 34% of students that took the Math CSEC in these four countries were able to pass the test and demonstrate the skills required to access higher education.

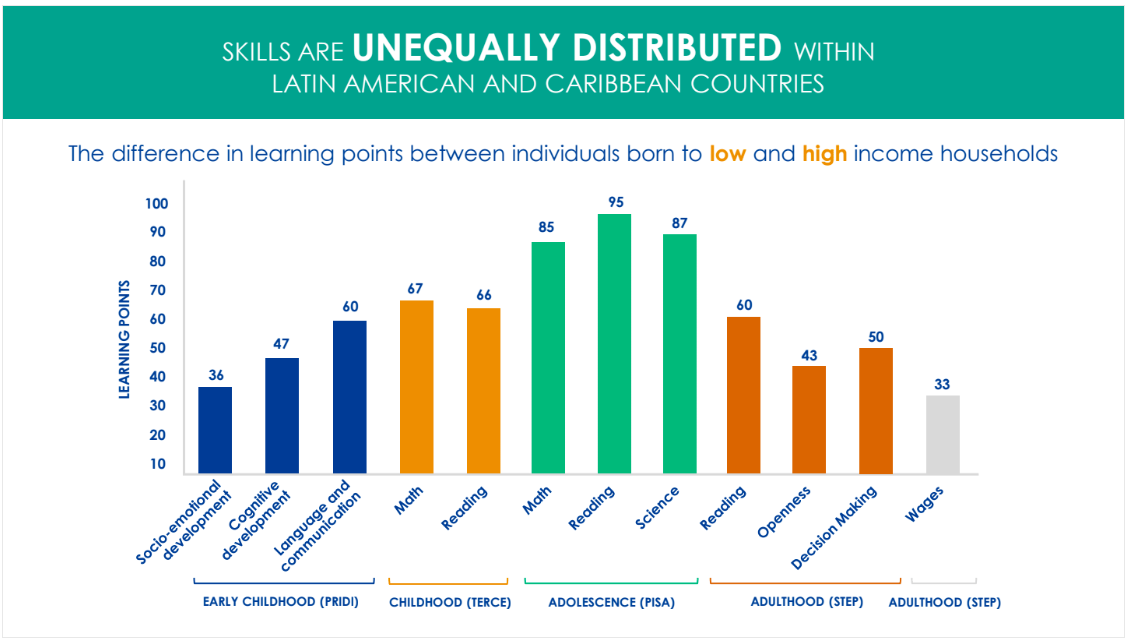

Equally disheartening is how inequality plays into the story. While the share of high performing kids in these standardized tests is far lower in the region than in developed countries, the skills gap between rich and poor begins early, widens from childhood to adolescence, and persists into adulthood where it is reflected in wages.

The figure below presents socioeconomic gaps over the life cycle. Gaps are measured in terms of a standard deviation. To give a sense of what this magnitude means, consider that, according to a study in the United States, during grade 5 children’s performance in nationally standardized math tests improves 0.4 of a standard deviation while during grade 10 that performance improves 0.25 of a standard deviation. Note, however, that measures are not comparable across different instruments and the sample of countries, due to data restrictions, varies across the different stages of the life-cycle. However, the gaps are large and persistent over the life-cycle in every country we could measure them.

The first three bars show the gaps in the Regional Program of Indicators of Child Development (PRIDI for its Spanish acronym). This collects data on children 24 and 59 months in four areas: language and communication, cognitive, motor, and socioemotional development in four countries: Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Paraguay, and Peru. Each bar shows the differences in scores between the richest and poorest quintiles. The differences in language development and cognition are large, while the variation is smaller in socioemotional development. Similar results were found in a study that used data from the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test in Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Nicaragua, and Peru.

These differences between rich and poor students are much smaller in developed countries. In adulthood, the World Bank’s Skills Towards Employability and Productivity Program (STEP) measures skills in low- and middle-income countries, including Colombia and Bolivia, and finds socioeconomic gradients among adults in academic and socioemotional skills as well as wages. Individuals with more educated parents reach adulthood with literacy and noncognitive skills (measured as intellectual curiosity and decision-making ability) that are 0.4-0.6 standard deviations higher than their counterparts with less educated parents. Because both cognitive and noncognitive skills affect wages, it is no surprise that these gradients in skills translate into gradients in wages: a person whose parents completed secondary education enjoys wages that are 33% higher than a person with the same level of education whose parents did not complete primary education. Parents with low skills, it seems, beget children with low skills and wages.

Poverty should not be destiny. But these results are not encouraging. Not only do they show that the region significantly lags behind the developed world in skills development. The inequalities baked into the region’s social systems also are perpetuated through the parenting process and the educational system to handicap the less fortunate even into adulthood. Parenting programs and educational reforms can begin to change that. And for the good of the region, the sooner that happens, the better.

Leave a Reply