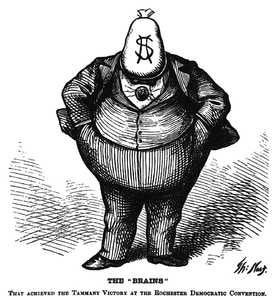

In the decades-long effort to make civil service bureaucracies more professional, civic coalitions have mobilized; business associations applied pressure; and international development agencies invested huge sums of money. Yet reform has frequently proved elusive. Instead, party-political rather than merit criteria reign in the hiring, promotion and firing of public employees. This so-called patronage in public employment continues to plague government bureaucracies from Mexico City to Jakarta. It is associated with corruption, democratic instability and worse socio-economic outcomes.

Some studies suggest that improvements in income, education and employment opportunities lead to demands at the ballot box for change. But despite better conditions for citizens in many parts of the world, 64% of non-OECD countries continue to prioritize political considerations over merit in hiring, according to a global survey. And, as documented in a 2014 IDB study, many Latin American nations still have classically clientelist, or patronage-based, bureaucracies.

What then can bring about the necessary renewal? In the end it may not be pressure from outside the political system but rather movement from within. That is to say that reform is most likely when politicians’ re-election depends on it and they have a strong self-interest in making it happen.

A recent IDB publication by Christian Schuster illustrates one circumstance when that occurs: A president or prime minister arrives in office without control over his legislature, and, as a result of the nation’s laws or constitution, the legislature rather than executive controls most patronage powers. Such a leader faces a much greater incentive to impose civil service exams and professionalize the civil service. He or she cannot compete in elections solely based on patronage: the opposition controls more of it. Reform offers a way out. It deprives the opposition of part of its ability to hand out jobs, salary increases or promotions, and use employment to win votes. Governments thus have incentives to professionalize their civil services when it hurts political competitors the most. Such a strategy has additional benefits as well: a president with a professionalized bureaucracy can run for re-election on better government performance and the benefits that brings to citizens.

Consider the cases of Paraguay and the Dominican Republic. Both nations had bureaucracies that were considered among Latin America’s least meritocratic in a 2006 IDB study. Both had presidents in Fernando Lugo (2008-2012) and Leonel Fernández (2004-2012) who were elected with, initially, little representation in congress. And both faced pressure to improve their civil services.

But events unfolded very differently in each country. Leonel Fernández had control over very few seats in congress when elected to office. Under the nation’s then constitution and legislation, however, he had power to approve and dismiss every single public servant in the executive branch, promote them, raise salaries and—with only limited legislative interference—increase the budget and size of bureaucracy. The Dominican president thus monopolized patronage control and could use it to his electoral advantage to appoint people who voted and campaigned for him. Unsurprisingly, a meritocratic civil service did not prosper under Fernández. While a new civil service law was passed on paper, the number of positions in the civil service filled through competitive, meritocratic exams never rose above 475 per year. The remainder were largely filled based on party-political criteria, and the country fell in the World Bank’s Control of Corruption Indicator from the 42nd to the 23rd rank (a higher number is better).

By contrast, Fernando Lugo not only lacked legislative allies; he also lacked control over part of public employment, promotions, pay and personnel expenditures. These powers, under the nation’s constitution and laws, rested in good part with congress. Unlike Fernández, Lugo thus had a strong incentive to professionalize the civil service. He was unlikely to win re-election for his movement solely through exchanging patronage for electoral support. But professionalization would deprive Lugo’s opponents of part of their ability to gather electoral support through patronage, while enabling him to court voter support based on better government performance and delivery of public services. His presidency was thus associated with a multiplication of meritocratic recruitment. From 2008-2012, public employment posts awarded through competitive exams rose from seven per year prior to Lugo to more than 11,000 and came to fill roughly a quarter of public sector vacancies. At the same time, Paraguay rose in the World Bank’s corruption indicator from the seventh to the 25th rank.

Lest anyone think that is a fluke of history, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909) also professionalized a blatantly patronage-based political system in the United States after finding congress in the hands of a rival in his party, with congress granted important patronage powers through the constitution and political custom.

Reform remains a difficult and, often, incremental process. But what these examples show is that it is also one that is most likely to occur when it secures a sitting president or prime minister electoral advantage. Personal aspirations may, of course, still matter: Roosevelt, for instance, is considered one of the great reformers of the early 20th century in the U.S. But when laws and institutions block a leader in a patronage system from using that system to his advantage, that leader has every reason to reform it. Fragmented control over bad government can incentivize good government reforms.

Guest Author: Christian Schuster is an Assistant Professor in Public Management at the University College London and was a Visiting Research Scholar in the Research Department of the IDB in 2013-2014.

Leave a Reply