Schools are closed in Latin America. Around 154 million children between the ages of 5 and 18 are at home instead of in class. It is not clear how long these closures will last, and there is a good reason for that: Schools provide a perfect environment for the spread of viruses. Students are typically in close contact to one another, packed into classrooms, playing at recess, and sometimes also eating side by side. Although most children do not seem to suffer severe symptoms when contracting Covid-19, they can still transmit the virus to the adults in their households. There is indeed evidence that closing schools in the middle of flu-like epidemics can reduce the peak infections rate by almost 40 percent.

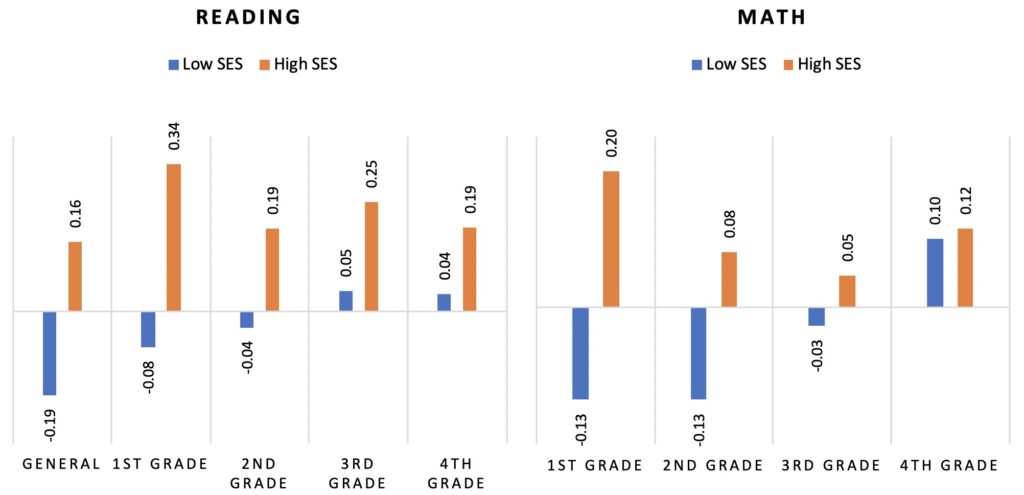

There are, however, costs associated with closing schools. Many families rely on them to provide daily meals for their children and childcare while parents are at work. In this note we focus on a different cost: the effect of school closures on learning losses. How can we quantify how much learning could be lost during the current pandemic? There are two sets of studies that could be informative. First, the so-called “summer loss” literature measures how much each student knows about math or reading at the end of the school year and again after two and a half months, at the beginning of the following academic year. The difference in tests scores is typically zero or negative and is known as the “summer loss.” We can translate this into how much children learn in terms of standard deviations. Figure 1 summarizes the summer-loss effect depending on students’ socioeconomic status. On average, over all studies and all grades, children from low socioeconomic backgrounds lose about -0.05 standard deviations over the summer, or the equivalent of 3 months of learning. Children of low-income families seem to lose knowledge of both math and reading compared to children of high-income families. When compounded over time, the differential summer loss can explain part of the learning gaps observed between these two groups that start very early on in life and widens as students age.

Figure 1: Change in Tests Scores Between End of School Year and Beginning of Following School Year

(by Socioeconomic Status (SES) and Measured in Standard Deviations)

Note: The results in these graphs come from Alexander et al. (2001) and Cooper et al. (1996). These were the papers where we found heterogeneous effects by socioeconomic status on summer loss. Other research on the topic, such as Quinn et al. (2016) were also revised but not included. The general effect comes from Cooper et al. (1996). This effect is the simple difference between the average fall and spring grade-level equivalent scores, and it expresses the change in achievement scores relative to US norms. This can be read as the decrease in the achievement average fall score equivalent to two months. In this study, middle income students are compared to low, here we include middle income students as High SES. Results for grade levels come from Alexander et al. (2001). We use their reported summer gains per grade and SES and divide it by the pooled spring exam standard deviation to report the effect in standard deviations.

Do the summer loss results apply to other situations? The short answer is yes. Another set of studies analyze the effect of teacher strikes (links here, here and here). These papers look at the learning of cohorts of students who were exposed to teacher strikes, particularly long ones, versus similar students who were not. The results of this literature are very much aligned with the ones observed in the summer loss literature. Long strikes affect negatively the grades of students in math, reading and writing. These effects have long-term impacts on these students, as they lead to fewer years of schooling, delayed graduation from high school, and a higher probability of being unemployed or not studying compared to students who did not experience a teacher strike. Additionally, these papers suggest that students affected by long strikes earn lower wages when they enter the labor market: a study in Argentina finds that being exposed to an 88-day teacher strike during primary school reduces annual labor markets earnings by 2.99%, as well as a decline in hourly wages.

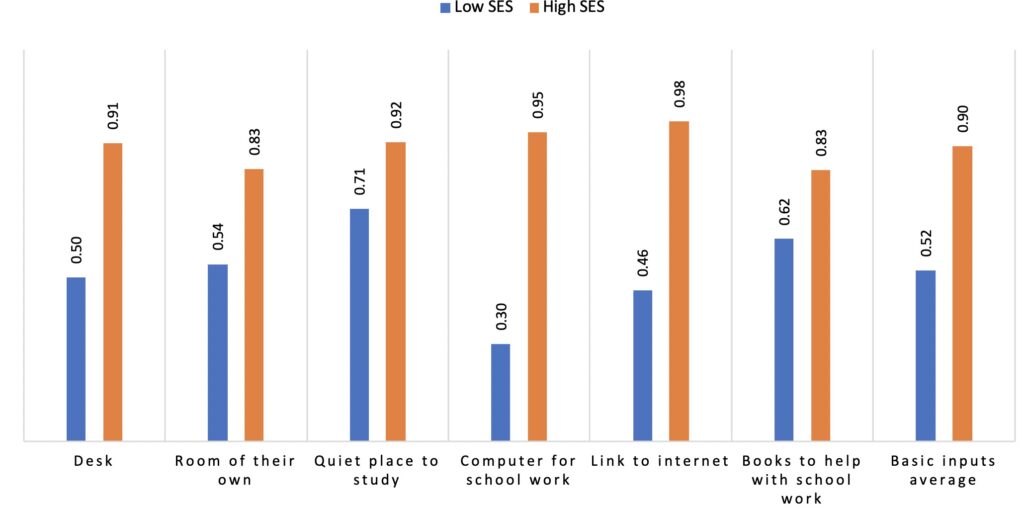

The conclusion of this literature is clear: children suffer learning losses when they are out of school. Naturally, many school districts in the region are trying to help teachers, students, and families to foster learning while students are at home (virtual lessons, through physical school material sent out to students and through phone calls, moving up summer vacations and providing school lessons through national TV programs, using radio, TV and the internet for homeschooling). Many of these initiatives require complementary inputs: both material inputs like books and computers but also time and human capital inputs from the parents. Unfortunately, access to school-related inputs is distributed very unequally across the region. Figure 2 shows the average share of households in the region that has access to different school inputs at home. There are very large differences in access. Almost all wealthier students have access to basic inputs for homeschooling while less than half of poorer students have access to a computer to do their schoolwork or access to the internet. These disparities in access to school inputs at home are fairly homogeneous across countries.

Figure 2: Average Proportion of Students in Latin America with Basic Inputs for Homeschooling

(by Family Socioeconomic Status, SES)

Note: Data used from OECD (2018), Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). The inputs average computed here is an average of the first 6 inputs shown. Averages for LAC include the following countries: Argentina; Brazil; Chile; Colombia; Costa Rica; Dominican Republic; Mexico; Panama; Peru; and Uruguay. High and low socioeconomic status is a category we created for the highest and the lowest quintile of the population using the PISA index variable for economic, social and cultural status by country.

The fact that low-income students tend to experience larger learning losses when they are out of school than students born to higher-income households could partially be explained by this differential access to school inputs at home. There is, however, an important difference between summers and current school closures imposed by the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. In summer, most schools do not expect their students to continue taking classes and learning. As schools in the region promote learning at home, they should consider strategies to help low-income families better educate their children. For instance, use of television or radio to distribute school content and lessons to keep students engaged are potentially successful strategies that have a long tradition in the region. In addition, countries should begin planning for remedial learning options to deal with the potential impacts of this pandemic on schooling. In a future article, we will offer a few examples of policies that have worked.

Leave a Reply