Latin America and the Caribbean is rich in natural beauty, cultural diversity, and resources. From the snow-covered peaks of the Southern Andes to the turquoise waters and the silky sands of the Caribbean, countries in the region are diverse in terms of human development, economic activity, and population size. One of the few common denominators they have is the high rate of homicides, closely related to organized crime groups.

However, organized crime is an ill-defined concept, which takes different forms in different countries. Throughout this diversity, territorial organized crime groups appear to be a significant part of the problem, even though they are not always the underlying catalyst behind high homicide rates. They represent a governance problem, as they emerge in areas where State control is weak.

Crime has become the main concern of people in the region, and many citizens are willing to trade their civil rights for security, according to surveys. In fact, crime erodes trust in democracy, as people begin to question democratic governments’ ability to provide adequate protection. In some contexts, citizens even begin to doubt that democracy is the best form of government for their countries, enticed by the perceived sense of control and security of more authoritarian regimes. This is an alarming development that needs to be tackled by policymakers.

The high rates of violence in the region come at a steep cost. The affected countries lose productivity and social capital; investors are turned away; public trust is damaged. Organized crime groups have ravaged Central America, where gang violence has forced the displacement of children and families.

A recent IDB study has quantified the high cost that Latin America and the Caribbean pays for its crime problem: around 3.5% of its GDP. The region has the highest levels of recorded homicide in the world, a real obstacle to sustainable development. Street gangs have turned El Salvador into the murder epicenter of the world, with one of the highest homicide rates outside of a warzone. In that country, the cost of crime reaches 6.16% of the GDP.

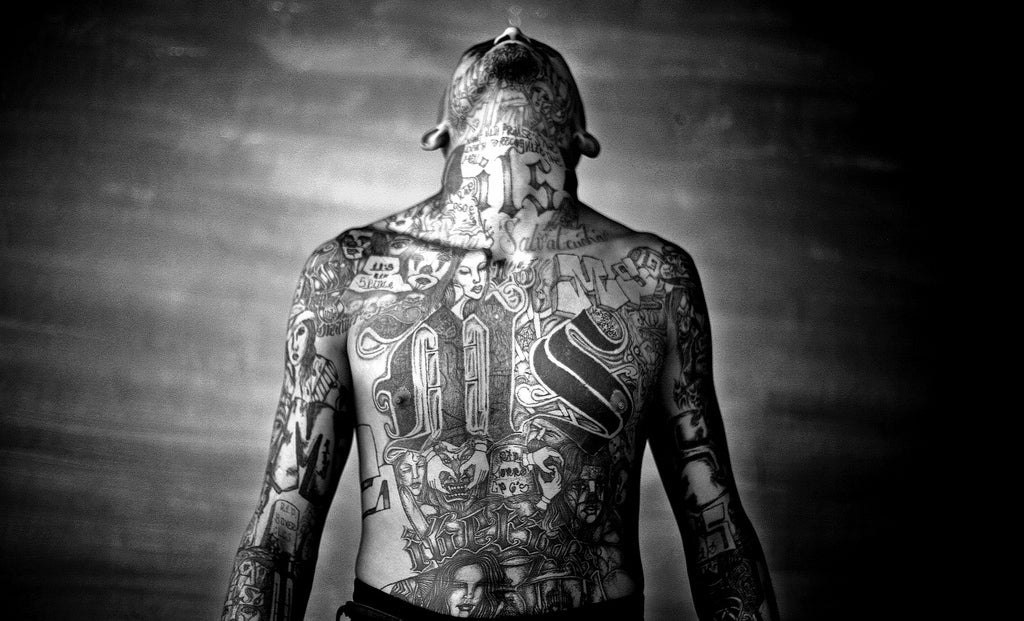

Street gangs’ members are mostly marginalized young men who live in cities and form a kind of surrogate family. They provide mutual protection and share a rivalry with similar groups. To them, economic activities—mainly extortion and the street drug trade—are secondary to territorial domination and the pursuit of respect.

As explained in the recent IDB study, these territorial groups often act as a surrogate State in areas neglected by the government. They impose a monopoly on violence, offering security to those who cooperate. To control their territory, they must be violent and notorious; they want everyone to know who is in charge and submit to their authority. They often interact with trafficking groups, as traffickers prefer to go through areas outside State control, a service territorial groups can provide for a fee.

Street gangs were imported to Central America’s Northern Triangle when immigrants to the United States were deported back to their home countries. That’s how these mafias of the poor developed in El Salvador, where violence is most tightly tied to the mara conflict. Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) was founded in the 1980s by Salvadoran emigrants in Los Angeles and quickly developed a rivalry with the multi-ethnic 18th Street gang (M-18), which also recruited from the Salvadoran community. Between 1993 and 2015, the United States deported nearly 95,000 convicts to El Salvador, equivalent to 1.5% of the country’s population.

Both MS-13 and M-18 became umbrella groups, absorbing local pandillas (gangs) into two opposing camps. The authorities adopted a mano dura (iron-fisted) approach, flooding prisons with gang members. In prison, members of street gangs often integrate into opposing prison gangs, and they continue with these affiliations once they are released back onto the streets.

The estimated 70,000 active gang members currently in El Salvador are believed to support a much larger network of affiliates and dependents, representing a significant share of the six million Salvadorans. According to the 2014 Latin America Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) poll, El Salvador was one of the countries in the region where more people reported they had been the victim of extortion (23%) and felt that gangs were a problem in their neighborhood (43%). On the other hand, drug trafficking only causes few deaths in that country as most of the cocaine passing though the Northern Triangle proceeds from Honduras to Guatemala, bypassing El Salvador entirely.

The IDB study also delves into the cases of two other countries that have a serious problem with crime and violence: Honduras, where the main issue is drug trafficking, and Jamaica, where the violence was originally rooted in the political process.

These examples provide just a glimpse into the variety of issues fueling violence in Latin America and the Caribbean. As mentioned earlier, not all violence can be attributed to organized crime, as many other factors play a role in explaining the disproportionate levels of crime in the region.

To release the brakes on development and progress in the region, governments need to reassert their territorial control. They must restore confidence in society, the economy, and democracy―a task that begins by ensuring that the people of Latin America and the Caribbean are safe in their homes and neighborhoods.

Leave a Reply