In his budget initiative to Congress for FY2016, U.S. President Barack Obama included a request of $15.297 billion to tighten border security and migration policy. In addition, he proposed including in the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) budget a $1 billion allocation to support security, governance, and economic development programs for El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

This move is a clear response—both preventive and reactive—to a major humanitarian crisis in the Western Hemisphere, where in 2014 approximately 51,000 migrant children traveling alone from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico were detained as they attempted to cross the U.S. southern border.

Several factors came together to produce a crisis of such magnitude, and packing suitcases and leaving one’s native land is no easy task—for the person migrating or for those left behind. Is it worth it? Do the benefits outweigh the costs? These are tough questions to answer, but they are precisely what this study is about: Financing the Family: Remittances to Central America in a Time of Crisis. In this book, researchers Gabriela Inchauste and Ernesto Stein suggest that migrant remittances to Central American countries are lifelines for many families, and they are used to justify the breakup of families, sometimes permanently.

Between 2005 and 2009, remittances covered between 80% and 100% of imports from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and the Dominican Republic, and 40% of imports from Nicaragua. Despite those high remittance rates, most Central American countries posted current account deficits during that period. Although those figures illustrate the macroeconomic significance of remittances, they do so only superficially, since what is most important is that remittances directly support the families that need them most. In this regard, many Central American families depend on remittances to avoid extreme poverty.

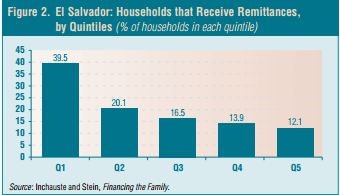

In El Salvador, for example, nearly 40% of families in the lowest-income quintile of the income scale and 20% of families in the second-lowest quintile receive remittances, and the funds received represent— on average—37% and 14%, respectively, of the expenditures of families in both quintiles.

That said, analyzing the effects of remittances on families that receive them is a bit more complicated to measure, for several reasons. One has to do with differences regarding training, skill level, and aspirations: emigrants who are most capable and diligent may tend to come from families with the same characteristics; these families have better economic prospects—even if they don’t receive the remittances that other families do.

Nevertheless, it is possible to interpret remittances as a magnification factor in household consumption or household investments. In a study conducted in 2007, it was found that lower-income families are inclined to devote most of their remittance income to basic needs, while higher-income recipients are more likely to use their remittances to keep their children in school or for other human capital investments. Those who receive remittances also tend to be healthier than those who don’t, both because they can afford more health care and because their relatives abroad impart knowledge they’ve acquired about healthier habits, including preventive health care.

Not all is rosy, however. Inchauste and Stein also mention possible adverse effects on children when their parents are away for long periods of time. Growing up without parents can increase the chances of children becoming exposed to risky behaviors or safety problems. Although these effects are certainly difficult to assess because of the monetary compensation families receive, it is worthwhile to bear them in mind.

In this context, Financing the Family: Remittances to Central America in a Time of Crisis is extremely relevant. President Obama is attempting to stop the flow of migrants using a two-pronged approach: on the one hand, by tightening border security and on the other, by supporting growth in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. In the end, the decision to leave one’s country lies squarely with each possible future migrant. Central America’s objective must be to achieve a level of sustained development such that each of its citizens can simply decide that leaving the homeland isn’t worth it.

Leave a Reply