7 min read.

Massive open online courses (MOOCs) are courses offered virtually with the aim of providing open and affordable educational options for people around the globe. Typically, MOOCs are used as a teaching tool in two ways: as a vehicle to replicate face-to-face classroom settings, or to innovate pedagogically. It is important to note that the use of technology in education is not itself the innovation, as the technology is neutral. Instead, value is added to instruction when technology is used strategically to create authentic learning experiences. Here is precisely where innovative opportunities with MOOCs can be found.

At the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the process of creating a MOOC begins with a needs assessment; this is where the target audience and learning objectives are defined. With these elements in mind we begin working on the pedagogical design of the MOOC: defining the content and developing the necessary didactic resources (videos, readings, infographics, etc.) that are adapted to the idiosyncrasies of the online learner. MOOCs are characterized by their flexibility with access and time, that is, the course remains open to the public for an extended period (several months on average), and the learners can undertake it at their own pace (self-paced) and autonomously, without the support of an instructor or tutor.

In this blog, we will explain how at the IDB we design activities within our MOOCs to add pedagogical value through the strategic use of technology. We will also reflect on a particular experience in one of our MOOCs, in which we integrated the tenets of storytelling coupled with the problem-based learning (PBL) methodology, also known as active learning.

Storytelling to bolster problem-based learning

The Problem Based Learning (PBL) methodology is especially useful for the MOOCs that we design at the IDB as they include content that is grounded in the bank’s empirical research findings and project results in the LAC region. Coupled with the this are the learning activities and assessments that emulate the reality of students, and in turn fosters the real-world application of knowledge acquired in MOOCs. A good example of this can be found in our course entitled “Water 2.0: Efficient Companies for the 21st Century” (Agua 2.0: empresas eficientes para el siglo XXI – only available in Spanish).

During the design of practical learning activities for the Water 2.0 course, we needed the PBL activities to be interrelated with each other and not just be isolated exercises per module. With this in mind, and to fulfill the role of the teacher in a sense, we created a common thread for these learning activities through storytelling. This approach supports the authentic learning process and the application of knowledge as students are prompted to critically think and actively consider solutions for the problems posed throughout the course.

To accomplish this, we mapped out and expounded on a story/narrative that transversally unites the PBL activities throughout the course. Specific to this teaching case we created a main character, named Carmen, who assumes the management of a Water and Sanitation company. In the following paragraphs we describe, step by step, the development of the storytelling for the MOOC activities:

- 1.- Determine the initial plot: During the course development process, the common thread of the plot and format of the learning activities were initially mapped out by both the learning experts and subject-matter experts (SMEs) on the team. In this case, the common thread would be the situation of Carmen assuming the management position at a Water and Sanitation company and the various challenges she faces.

- 2.- Generation of inputs (as text): the subject-matters experts, who are versed in course content that is based around challenges of the region, identified real-life scenarios that could be represented and communicated through various educational resource inputs (text, videos, readings, interactions), within the context of the MOOC. On this occasion, the inputs were related to the challenges commonly faced by Water and Sanitation companies in Latin America and the Caribbean. These inputs formed the basis of the learning activities in each module, connected by a ‘transversal story plotline’, which we will explain further in the next step.

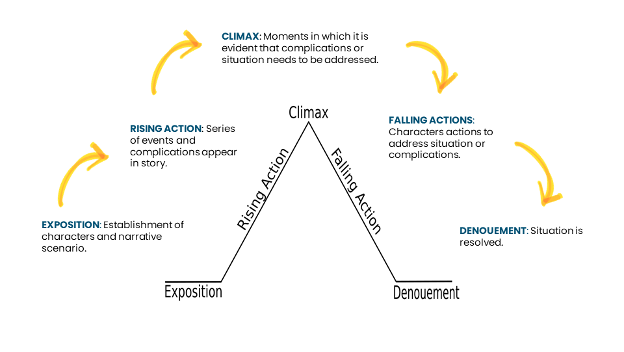

- 3.- Selection of a storytelling model: The learning experts on the course development team selected Freytag’s pyramid of dramatic structure as the most appropriate storytelling model to connect the problem-based learning activities within the course:

- 4.- Creation of the first draft of the activities: using the selected storytelling model, the learning experts generated written drafts of both the activities and the story that connects them, the common thread. Once ready, the drafts were shared with the subject-matters experts for revision, feedback, and approval. Note: if the activities will also be presented in other formats (video, animation, third-party tool, etc.), it is important to revisit this step, since final sign off by the SMEs is critical in ensuring that the story is represented in a real-world context.

- 5.- Use of digital tools: to maximize the effectiveness of storytelling in the course, it is important that your digital tools of choice provide a meaningful and authentic learning experience. In this sense, it is necessary to select a software that allows for the possibility of animating the story in diverse formats. Access to contemporary digital devices and varying internet connections speeds must be considered as well. The digital tool(s) must also allow for mapping different learning routes or pathways that the participant can choose from as they advance in the learning objectives. Moreover, the tool must allow for learning activities to be designed in a way that provides ongoing feedback as the learner selects and makes decisions towards resolving the problems posed.

- 6.- Test the Learning Management System / Platform: a time was designated, before the course began, so the team could test out how the activities worked and were displayed once uploaded to the learning platform where the MOOC was hosted.

- 7.- Evaluation: finally, the teams select the most appropriate tool to provide and obtain feedback on the problem-based learning activities from the students. For this MOOC, a digital survey was used that students could access at the end of the course.

Each aspect of PBL learning and its interaction with storytelling for this MOOC was designed to move the student from a position of passive information assimilation, to being an active participant in their learning process. Students were able to familiarize themselves with the course content at their own pace, and had full control to navigate the back-and-forth of various multimedia activities, help sections, and PBL branching scenarios.

As we have seen, for the MOOC “Water 2.0: efficient companies for the XXI century”, we incorporated several teaching strategies that include PBL learning, an established narrative framework (storytelling), and digital tools to develop interactive activities.

The combination of these strategies turned out to be a very positive learning experience, because the participants were able to build and work with concepts based on real problems and, at the same time, develop viable solutions that could be replicated in the real world. This combination favored not only the acquisition and understanding of knowledge, but also the possibility of providing feedback on the decisions made by participants. This pedagogical innovation also fostered the development of problem-solving, critical thinking and decision-making skills, in conjunction with technical knowledge gained form the course. All of these are highly valued skills these days across various organizations.

Would you like to know more about IDB MOOCs? Visit this edX page and do not miss the opportunity to continue learning.

Do you also develop online courses? Or have you participated in any as a student? Comment below and tell us what activities you liked and in what courses.

By Verónica Sánchez, Marie Reid and Andrea Leonelli of the Inter-American Institute for Economic Development (INDES) of the IDB

Leave a Reply