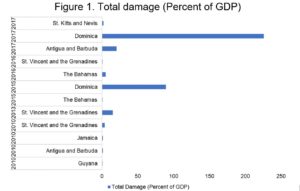

Preservation of life and property is the most pressing instinct when faced with the threat of a natural disaster. But after survival, the next phase – recovery – can be the more arduous and complex feat. Since 2010, the Caribbean region[1] incurred an estimated US$3.2 billion in damage to housing, crops, and infrastructure while total deaths amounted to nearly 180 persons. At the same time, the IMF[2] indicates that the economic impact of natural disasters weighs more heavily on these small economies; the average cost of disaster damage each year in the region is about six times higher (2.4 percent of GDP) compared to 0.4 percent of GDP for larger states.

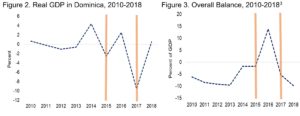

Dominica is a clear illustration of the scale of disruption to the economy that one extreme weather event may have on small island economies. As highlighted in the recent IDB publication, Together for Prosperity in the OECS, damages as a result of Tropical Storm Erika in 2015 stood at an estimated US$483 million, or around 90 percent of Dominica’s GDP. Total persons affected as a share of the population stood at around 40 percent and over 570 people were left homeless. While still on the path to recovery from Tropical Storm Erika, the island was severely impacted by its worst natural disaster two years later – “Hurricane Maria”, which resulted in damages estimated at US$1.3 billion or 226 percent of GDP (see Figure 1). At the same time, real GDP fell by -9.5 percent in 2017 following growth of 2.5 percent a year earlier (see Figure 2). Moreover, the fall in tax revenue after the hurricane led to a sharp decline in fiscal performance (see Figure 3) and an accumulation of public debt to around 83 percent of GDP at the end of 2018.

Given the frequency and destruction caused by these extreme weather events, Caribbean countries have been exploring climate-resilient debt instruments and other innovative means to build financial resilience. One such way has been the introduction of a hurricane or similar disaster-linked clauses in their loan agreements.

The hurricane clause is designed to provide cash flow relief at the crucial period after a natural disaster event, when financing needs are high and new sources of funding are limited. By embedding “hurricane-linked clauses” in debt contracts, countries can tap into extended maturity periods in the event of a natural disaster. This would allow a disaster-hit country to defer either interest payments or principal or both for a defined period. In the region, such clauses were first utilized by Grenada, and more recently by Barbados.

In August 2018, the authorities in Barbados rolled out the Barbados Economic Recovery and Transformation (BERT) program. This economic reform program also provided the macroeconomic framework for the IMF’s Extended Fund Facility (EFF) support program. One of the key elements of the program included a comprehensive debt restructuring, including both domestic and external debt (while negotiations with external creditors are ongoing, an agreement with domestic creditors was reached on October 14, 2018). The Government was able to successfully negotiate natural disaster clauses in its restructured government bonds. In this case, it allows for capitalization of interest and postponement of scheduled amortization falling due over a two-year period, following the incidence of a major natural disaster. The trigger for a natural disaster event would be a payout above a prearranged threshold by the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility under the authorities’ catastrophe insurance policy.

Limitations exist with respect to these clauses, as they would mainly apply to new debt while some investors may only be willing to accept them at higher interest payments. However, they have received some support from the international financial community as a means of reducing the possibility of default among vulnerable countries such as those in the Caribbean region, that are susceptible to the impact of global climate change.

In its 2019 – 2023 Country Strategy with Barbados, which envisions up to US$300 million in investment lending, the IDB Group proposes the use of its contingent credit facility instrument to respond to a natural disaster emergency. The facility mechanism allows for a rapid transfer of funds to cover immediate financing needs that may arise following a natural disaster until other sources of funding are available. In 2018, both The Bahamas and Jamaica signed agreements with the IDB to access this contingent facility, while Suriname signed a similar agreement in March 2019.

It is a step that makes sense for the increasingly vulnerable countries in the Caribbean. Continuing to seek innovative methods to reduce risks linked to natural disasters allows them to meet debt service payments in the aftermath of a natural disaster and creates much needed additional fiscal space for recovery.

Notes:

[1] This covers the C6 countries: the Bahamas, Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago and the OECS region which includes Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia and St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

[2] Acevedo, S. 2016. Gone with the Wind: Estimating Hurricane and Climate Change Costs in the Caribbean. IMF Working Papers, WP/16/199, October 2016.

[3] The overall surplus recorded in 2016 was primarily driven by an increase flow of funds from the Citizenship by Investment Programme.

Leave a Reply