It should not be surprising that crime is usually at its most intense in cities. Populations and economic activity are most concentrated there and criminals there enjoy the most profitable targets. But with 43 of the world’s 50 most murderous cities and urban crime on the increase, Latin America and the Caribbean is an extreme case and in desperate need of better tools to fight the scourge in its metropolitan areas.

One of the most effective weapons in the crime-fighter’s arsenal is what is known as hot-spot policing, the laser-like focusing of police personnel and resources on small geographic units, tinier even than neighborhoods or blocks. Research in the developed world, combining police reports, crime analysis, and Geographic Information Systems, has found that crime usually occurs on fragments of blocks, known as street segments (two sides of a street between two intersections). Five percent of such segments, according to work pioneered by David Weisburd, tend to generate more than 50% of a city’s crime in a given year. These may consist of a neglected, low-income housing project or other manifestation of poverty and inequality. But they could also be higher income places or high tourism locales that make for easy targets. In either case, it’s often not helpful to talk about good or bad neighborhoods: there are safe and dangerous street segments in all types of neighborhoods, and it is there the police must focus their efforts.

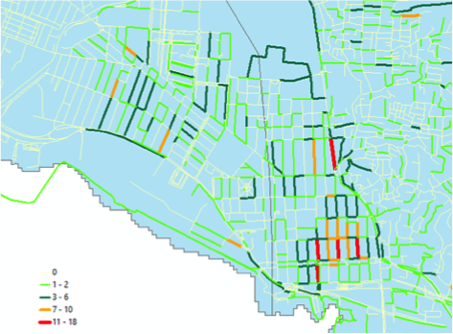

A similar truth holds in Latin America and the Caribbean. In an IDB study by Nicolas Ajzenman and I, we examine five cities in Latin America, including among them, Bogota, Montevideo and Belo Horizonte. We show that over a three to 10-year-period, 50% of crimes are concentrated in 3% to 7.5% of street segments. Similarly, in a close examination of Port of Spain in Trinidad and Tobago, we find that, according to police reports, only one in four street segments experienced a crime in 2014, and that some of the street segments that registered large numbers of crime incidents (the ones on the map in red) lay next to segments with very few crime incidents (the ones in green).

CRIME IN PORT OF SPAIN, TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO

Crime incidents at the Micro-level. Lines indicate street segments

For crime to occur three elements have to be present: a victim, an aggressor and an opportunity. Because all those conditions have to be met, crime tends to persist in a chronic fashion in the same places, with 40% to 66% of the hot spots in Latin America still crime ridden or “hot” over a 3- to 10-year period.

All this reveals why random patrols and unfocused enforcement efforts prove generally ineffective. Police usually don’t just encounter crime. They must gather information as to where it occurs and persists and target it with surgical precision at the micro-level.

Police intervention as well as other factors can cause crime to shift or displace geographically, creating new hotspots over time, a reality that police need to take into account. That means considering the potential and underlying causes of crime in any given locality. And it means being aware of social problems in that place. For example, in the United States street segments with serious mental health and substance abuse issues often coincide with ones with significant levels of crime, suggesting a need to deal with the full scope of social problems in a coordinated fashion.

Ultimately, as the theories of crime economics hold, we need to figure out how to make crime less attractive. That involves better deterrence and greater incentives for engaging in legal activity, whether that be through greater educational, employment or other opportunities.

The micro-level is always useful. Urban crime may be widespread, chronic, and devastating in both its personal and economic dimensions in Latin America and the Caribbean, but if we examine the problems behind it in the smallest geographic units, we may find new solutions.

Leave a Reply