From the first words that parents exchange with their children to the games they play, the intellectual and emotional stimulation parents provide is critical. Especially in the early years, sustained and effective parenting can lead to greater intelligence, sociability and mental health.

Thus the shock in the mid-1990s when researchers in the United States found that by age four, children of professionals had heard 30 million more words than low-income children. Moreover, the type of parent-child interaction differed dramatically. A child in a family of professionals would have heard 560,000 more encouraging words than discouraging ones. A poor child, by contrast, would have heard 125,000 more critical than affirmative words. The good fortune of being born into a well-off family, it seemed, provided a leap right out of the starting gate.

Social class creates inequality in skills development

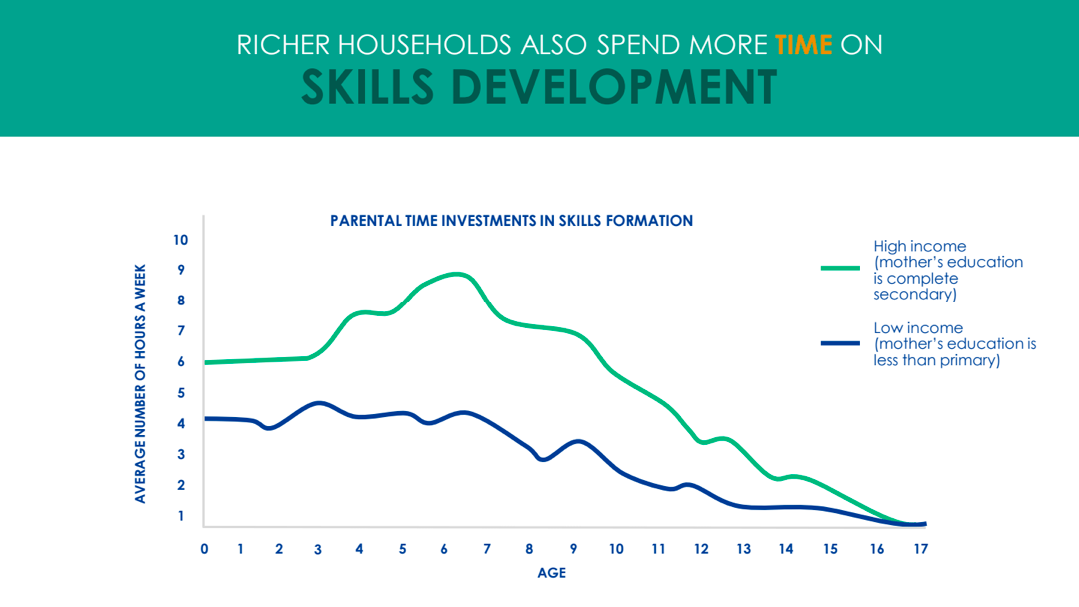

What is true in the United States is probably even more true in Latin America and the Caribbean. The gap between rich and poor in terms of the amount of time parents have to spend with their children—and in many cases the quality of that time—is enormous. This may be in time talking, reading, playing with their children, helping them with their homework or all of them together.

In terms of just sheer amount of time, it may be because the poor are working many jobs. It may also reflect their failure to understand the importance of early stimulation to boost cognitive and socio-emotional skills. But the total amount of parental time invested in activities that boost a child’s skills tends to be a function of social class.

The gap begins early, when children most benefit emotionally and intellectually from their parents’ attention. When a child is two, a family of high socioeconomic status spends about two hours more per week in helping that child develop skills than a family of low socioeconomic status. By the time the child reaches seven that gap has widened to five hours per week. In Honduras, to cite an extreme case, around 70% of parents in the bottom quartile of the income distribution help their third grade children with homework, compared to around 95% for the top quartile. In Panama, the figures are around 80% and 98% respectively.

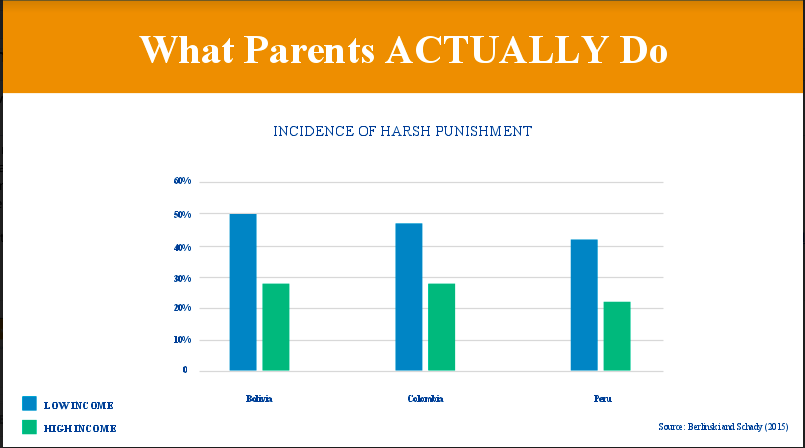

Of course, as previously mentioned, it is not only the amount of time that matters. It is also the quality of that time. One measure of home interactions can be found in the prevalence of harsh punishment or child abuse. In Bolivia the incidence (measured as once in a lifetime) of harsh corporal punishment is around 50% in low income families and close to 30% in high incomes ones, while in Peru, the figures are roughly 40% and 20% respectively.

.

Whatever the metric, the results are dramatic. As we show in our recent flagship report Learning Better: Public Policy for Skills Development the difference in parental attention and treatment contribute to a chasm in ability such that by the third grade, a child from a low socioeconomic background in Latin America and the Caribbean lags 1.5 years behind a child from a high socioeconomic one, a devastating handicap at such a young age.

An inequality in skills that is far higher than in the OECD

All these failures build on themselves, snowballing, so that not only do the countries of the region perform way below those of the OECD on the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) exam, but that the inequalities in scores are far higher than in OECD countries. Ultimately, it also means that the region lags far behind its aspirations in productivity. Children are the adults of the future. Spending lots of time with them and spending it well is one of the best investments that a family and a society can make.

Leave a Reply