Latin America and the Caribbean suffers from low productivity. The slow growth in productivity per worker in the region has weakened its economies and made countries unable to satisfy the burgeoning needs and demands of their citizens. The Covid-19 pandemic has only highlighted this chronic problem, revealing a significant technological gap between the region and the advanced economies.

One of the most urgent challenges for the region is thus to strengthen and energize innovation research, development, transfer, and implementation ecosystems to accelerate productivity. The region must provide adequate government support. It must create an environment in which innovation can flourish and high quality start-ups can attract investors and help boost growth — an issue discussed at a recent IDB conference which brought together academics, researchers, regulators and practitioners.

The Old and New Ecosystem in Innovation

Understanding the modern innovation ecosystem is key to fostering productivity in Latin America and the Caribbean. Traditionally, innovation was “closed”. Big corporations were the main actors, generating ideas, developing and executing them and monetizing them in their own markets. This was expensive and exclusive, and few firms could afford to innovate. Indeed, because many firms could not profit from their innovations, new ideas often languished.

The Open Innovation (OI) paradigm is the new way of technological progress. In this world, ideas flow across firms’ boundaries. Innovation is no longer closed, centralized, and internal to each company. Valuable ideas come from outside the company as well as from within, mixing with its know-how to create new products or services, and potentially catering to markets different from the ones traditionally served by the firm.

As OI arose as the main driving force of innovation, start-ups stole the show, but they required an ecosystem to thrive: Venture Capital funds (VC) and business accelerators became key enablers. Indeed, as pointed out by Josh Lerner of Harvard, the top 10 of global companies by market capitalization in May 2020 were VC backed (Alibaba, Alphabet, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft, and Tencent), and none of them existed in 1950.

Business accelerators are programs that provide a cohort of young start-ups with non-monetary resources and sometimes cash during a fixed term. They can be thought as schools for entrepreneurs, providing education, business training, customized guidance, exposure, and opportunities for networking, among others. Though evidence on their efficacy in the world is still thin, they appear to have sizable added value for participants, according to Juanita González-Uribe of the London School of Economics.

Corporations’ role eventually evolved from ultimate buyers of innovation to include start-up funding and mentoring. They have started their own venture funds, known as Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) and corporate business accelerators. Both types of initiative leverage the corporation’s knowledge and alleviate constraints to start-ups growth: Lack of information about client needs and demand for services, lack of know-how, exposure, and restricted access to complementary intellectual property.

The Region’s Ecosystem Development

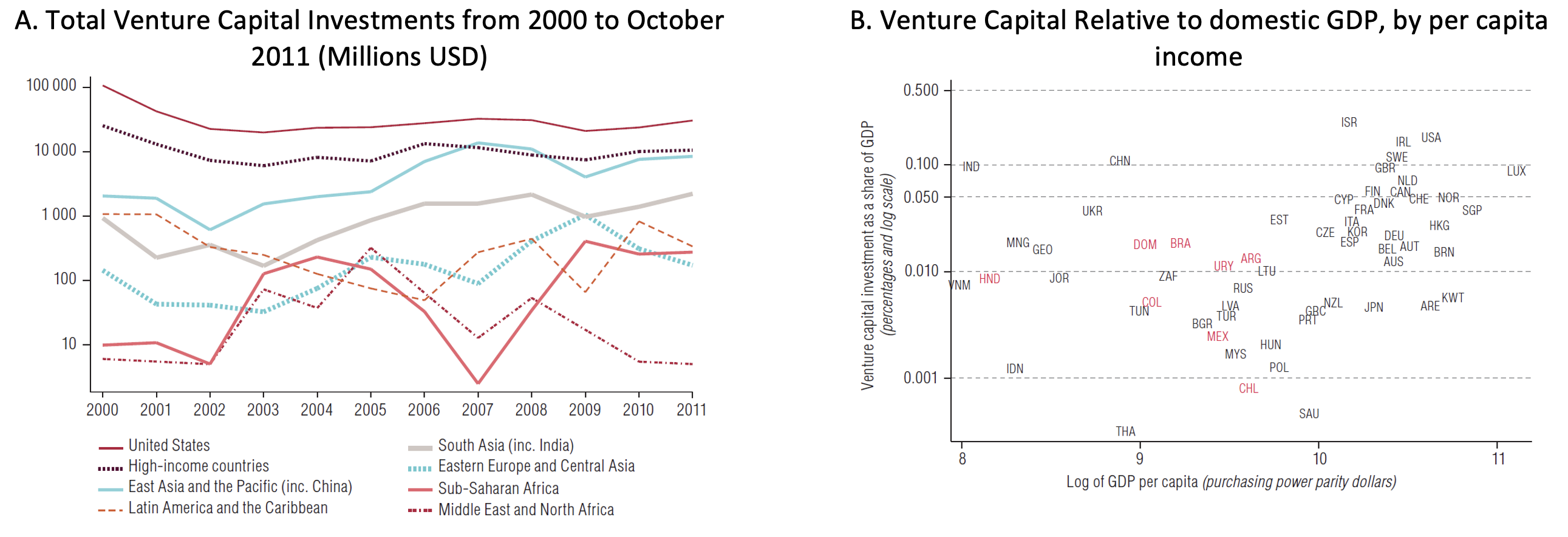

Venture Capital funds are an important entrepreneurial financing source in developed economies, not only producing more but higher quality innovations. While there is some VC involvement in Latin America and the Caribbean, their market share is small when compared to other regions (see Figure 1). Successful financing rounds by unicorns in the region, like Rappi in Colombia, Nubank in Brazil, and dLocal in Uruguay, signal that investors have funds ready to take advantage of opportunities. But it is nonetheless a challenge to find start-ups worthy of investment that will generate aggregate value to an economy, according to funds’ managers and government officials participating in the conference.

Figure 1. Venture Capital in Latin America

The lack of suitable start-ups in the region makes the case for business accelerators. A study of Start-Up Chile, a government-sponsored accelerator, by González-Uribe found that it effectively increased the performance of start-ups with high potential, their likelihood of raising capital, the amount raised, and the number of jobs created. Valle-E, a business accelerator program in Colombia that provides training to entrepreneurs, has resulted in 166% more sales growth on average for ventures that participated in the program than for similar ones that didn’t. However, many ventures did not show improvement after participating, and most of the benefits were concentrated in the ones that looked more promising before the program. Hence carefully selecting participants is critical to capturing the full benefits of accelerators.

Corporations have also played an important role in the ecosystem. As corporate venture capital has gained more popularity in recent years, companies within the region have started to foster and mentor new start-ups, while creating departments and funds to support and invest in start-ups and manage corporate venture capital. A few examples are: Alianza Team, Krealo, Wayra, and YPF Ventures. Companies have also started to engage more in accelerator programs. While corporate venture funds from the region connect to global innovation ecosystems and bring home new ideas, however, the region is not encouraging innovation within, according to fund managers at the conference. This is contributing to the region’s failure to close the gap with developed economies.

The Government’s Role

Governments have long been interested in fostering innovation, but old policies may not have enough bite. Tax subsidies for research and development, for example, may not be effective enough, as most innovative start-ups do not generate profits until many years after the innovations occur. Instead, the relief ends up in hands of corporations with marginal incremental innovations and clever accountants, instead of in the hands of disruptive inventors that generate huge technological gains.

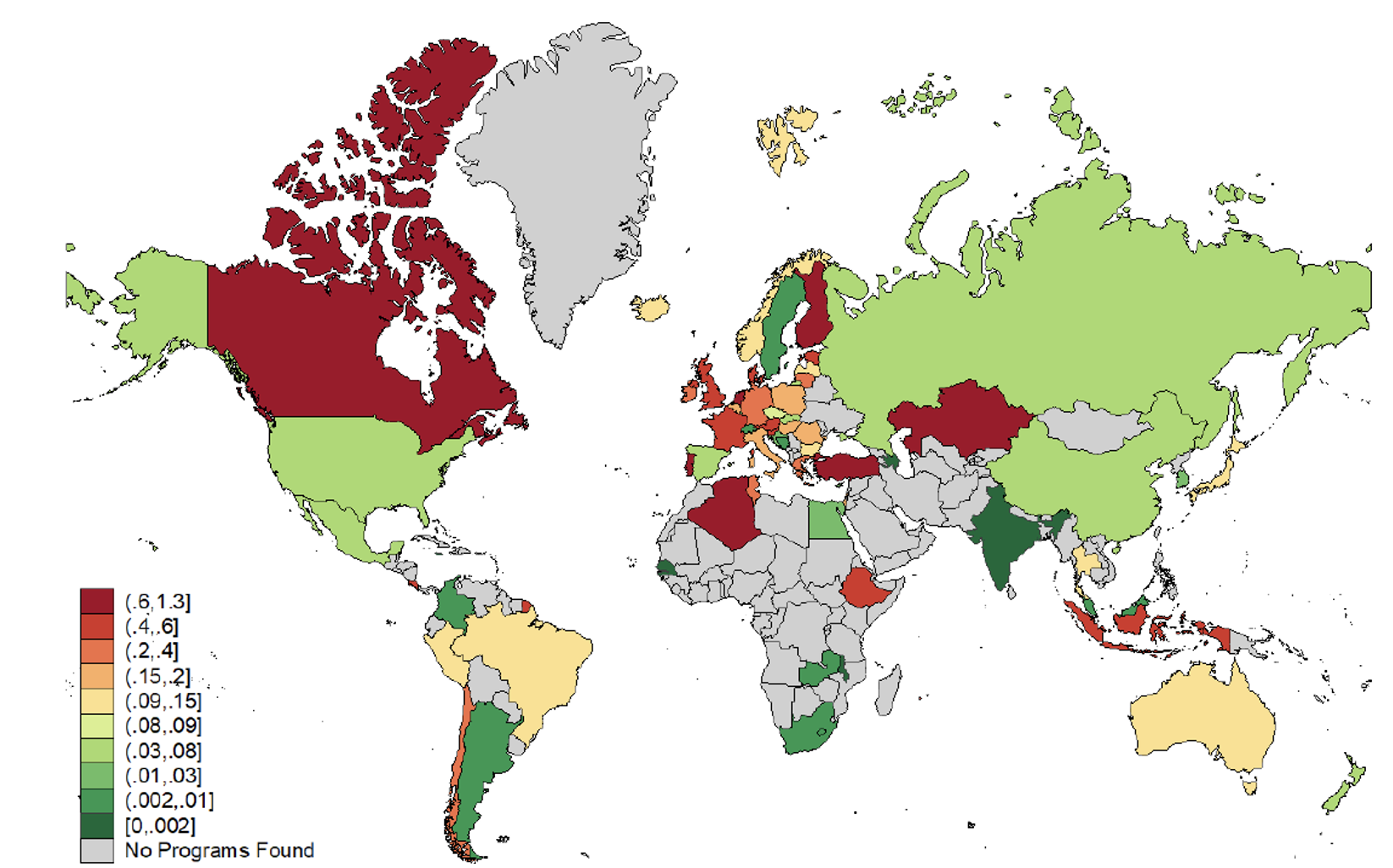

Governments have increased their spending on VC funding programs over the last decade, according to Harvard’s Lerner. Figure 2 exhibits the average annual budget relative to GDP of entrepreneurial finance policies between 1995 and 2019 for several countries. The average government entrepreneurial budget share of GDP in the region is smaller than those of other regions, consistent with the region’s slow productivity growth. Several countries with large budgets, meanwhile, are seeing meager returns on their investment, suggesting that increasing spending is not enough. When the government increases its involvement, bad governance and poor surveillance can also be a problem. While this is the case for most government programs, it is particularly acute in innovation policy because most start-ups fail, making it harder to guarantee government accountability and opening the door to favoritism and resource misallocation.

Independent institutions and programs, and collaboration with private parties can help alleviate some of these issues. Both lead to better governance, the former by shielding venture funds and managers of accelerators from favoritism or political influence, the latter by bringing expertise and skin-in-the game from private actors. The success of the “Start-Up Chile” accelerator shows how an independent public institution can overcome such issues.

Figure 2. Average of annual budget/GDP (%) of government’s entrepreneurial finance policies active between 1995 and 2019

Conclusion

VC and business accelerators are key players in the innovation ecosystem. While their presence in the region has grown significantly in recent years, the region’s share of global innovation ventures is still very low, weakening economic growth prospects. The region urgently needs to increase its supply of start-ups with high potential. Investors are ready to take on worthy opportunities, but governments must strengthen the environment, while taking steps to ward off unintended consequences. Private partners in the form of venture funds and corporate business accelerators are key to that mission, mitigating accountability and governance problems, while bringing key knowledge from corporations into the innovation ecosystem.

Leave a Reply