Three years after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) are still dealing with its economic consequences. Currently, one of the main points of concern is the excessive level of public indebtedness and the risk it represents to economic stability and economic growth.

This year the IDB published its flagship study Development in the Americas – Dealing with Debt: Less Risk for More Growth in Latin America and the Caribbean. It shows that the pandemic accelerated the pace of public indebtedness and slowed economic growth in the region, a trend that had already been emerging in previous years.

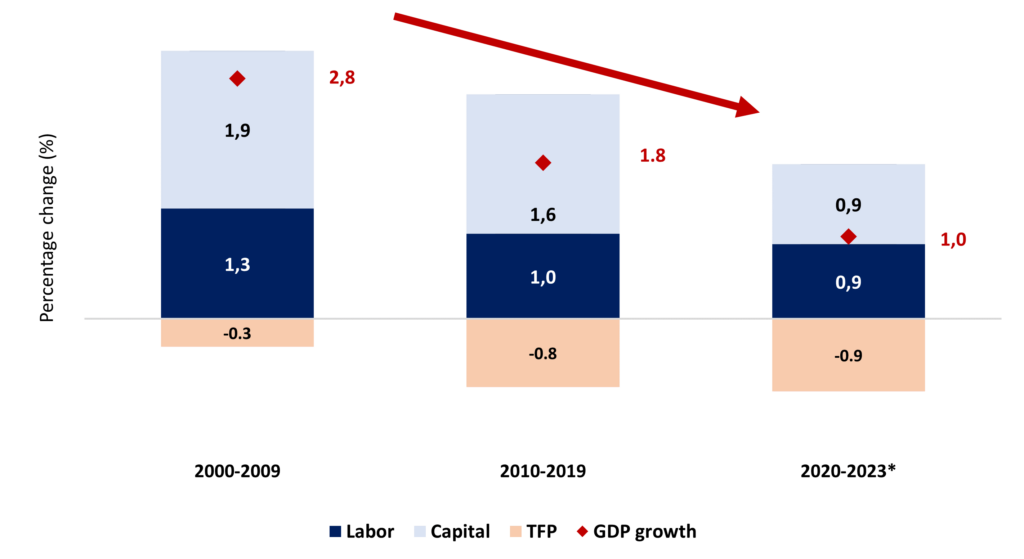

Since 2020 public debt levels rose by 15 percentage points (pp) of the region’s gross domestic product, to 71 percent. That adds up to the 18-percentage point increase between 2014 and 2019. Unfortunately, increased debt has not helped boost growth nor overall economic productivity. Figure 1 below shows that economic growth has been slowing down in the region because of a reduction in total factor productivity, especially of labor and capital. Economic growth in the region has gradually slipped to a mere average of 2 to 2.5% in the medium term.

Figure 1. Economic Growth Decomposing for LAC

Figure 1 shows the decomposition of GDP growth by factors in average through the last decades. IDB staff calculations based on The Conference Board’s Total Economy Database (TED). (*) Data for 2022 is estimated and for 2023 is projected.

Having a high level of debt is costing the region dearly. LAC countries are currently spending about 5 percent of their GDP to service this debt, similar to their investments in vital sectors like health and education, which are key to boost long-term productivity and growth. Adding to this challenge is the current international scenario, including the war in Ukraine, global supply chain disruptions and rising interest rates to combat inflation, which can affect investor appetite for investing in the region and financing its debt.

In this context of high levels of public indebtedness and uncertainty in international markets many are wondering what effects these high debt levels can have on future economic growth. Even though this is an old question among economists, answering it is difficult, as the relationship between debt and economic growth depends on many factors.

In the next paragraphs we discuss three factors our flagship study identified as crucial for policymakers to ensure debt does not become a drag on growth in the years to come.

The Debt-Growth Nexus

Debt can affect medium- and long-term growth both directly and indirectly. The direct impact is related to how governments use the proceeds from debt sales. In the short run, debt can finance higher government spending, which increases aggregate demand and the gross domestic product of a country. If this spending is devoted to investment projects, human capital accumulation or innovation, it can also stimulate medium- and long-term growth. This effect can be particularly important in countries with scarce physical and human capital.

But public debt can also have indirect effects on growth, which can be detrimental. For instance, excessive public debt can increase a country’s default risk, limiting access to financial markets. It can shift government spending from productive investments (i.e. infrastructure) towards less economically productive spending (i.e. interest payments). Moreover, it can lead to crowding out effects, as higher public debt can increase domestic interest rates, which reduces private sector investments.

Debt Levels Matter

Whether the direct or indirect effects are quantitatively high depends on many factors. One of them is the current debt level of a country. Our research finds that debt typically increases growth if initial debt is at relatively low levels. However, debt reduces growth if starting debt is already high. This means that there is a tipping point, or threshold, at which higher debt levels become detrimental to growth.

The debt threshold is not the same for all countries because it can be influenced by different factors such as the economic structure, for example. For LAC countries, this threshold is at approximately 53 percent of GDP. This level is similar to a group of emerging economies, for which these levels hover at around 48 percent. Still, this level is well below that of developed countries, where the debt threshold stands at around 95 percent of GDP.

Institutional Quality Matters

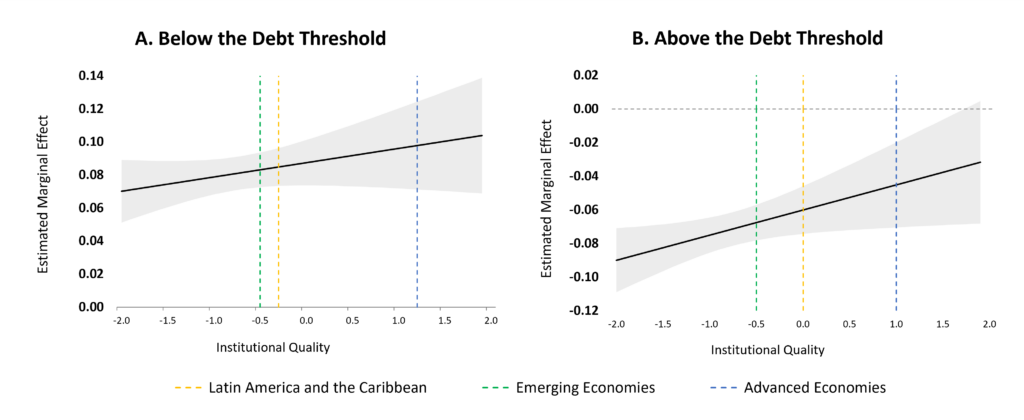

Another important finding of our research is that the effect of public debt on growth depends on institutional quality. In our research we calculated how the marginal impact of debt on growth changes when the quality of the institutions changes.

The results are presented in Figure 2 below. As mentioned before, debt increases growth when debt levels are low. Panel A shows that this positive effect becomes larger in contexts of higher institutional quality. Similarly, Panel B shows that the negative effect of debt on growth when debt levels are high becomes smaller as institutional quality increases.

Figure 2. The Marginal Effect of Public Debt on Growth

Figure 2 shows the estimated effect of public debt on growth above and below the threshold. IDB estimates based on WEO-IMF, World Bank, and Penn World Table. Estimates obtained using a panel model with threshold effects (Hansen 1999, Seo and Shin 2016). Instrument for public debt built in two stages: i) regress SFR on inflation, valuation effects, debt default, and debt forgiveness, and ii) predicted values are used to instrument public debt.

Countries Must Avoid Debt Spikes

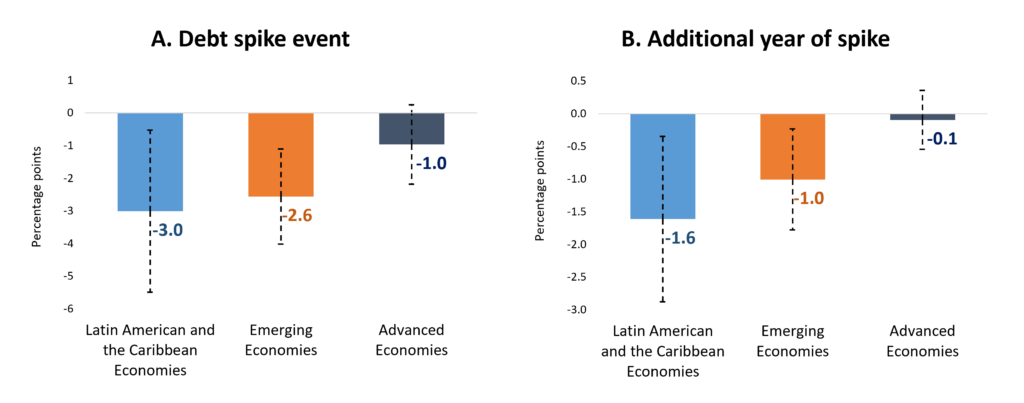

Another factor that has an important impact on the relationship between debt and growth is debt spikes, or rapid and substantial increases in debt1. Our study shows that such spikes are consistently associated with decreased economic growth across various country groups (Figure 3). In LAC, these spikes lead to a significant 3 pp GDP growth reduction. Additionally, the longer a debt spike, the more profound is its adverse impact on growth. Each additional year results a 1.6 pp of decline in growth.

Figure 3. The Effect of Debt Spikes on GDP per Capita Growth

Figure 3 depicts the expected impact of debt spikes on economic growth, both the event effect (A) and its duration (B). IDB estimates are based on WEO-IMF, World Bank data, and Penn World Table. Estimates obtained using Arellano-Bond regressions. Shown points estimates correspond to the estimated average effect.

The qualitative results are not surprising, as debt spikes generate high uncertainty and have broad effects on public and private investment as well as on sovereign risk. In LAC, government capital expenditure as a percentage of GDP falls by 2.9 pp during debt spikes, and private investment decreases by about 4.4 pp of GDP. Additionally, sovereign risk in the region increases during these events, with a substantial 700 basis points rise in the EMBI spread, often leading to at least one credit rating downgrade.

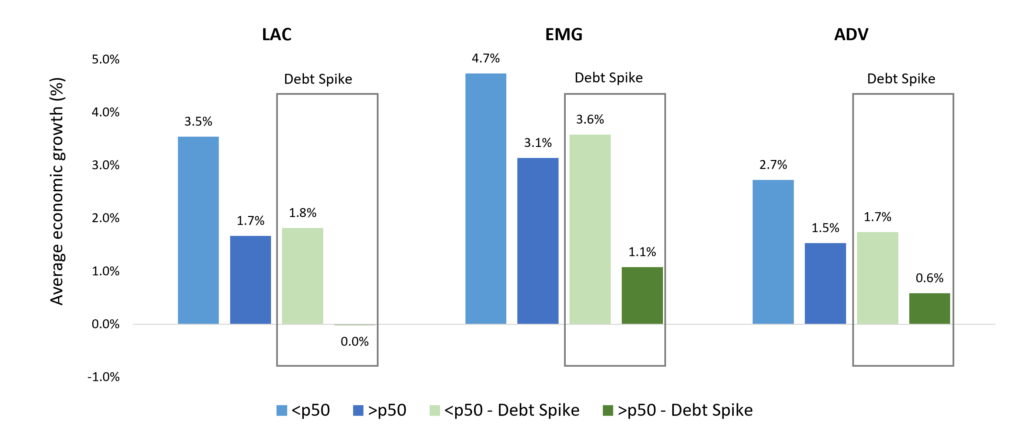

Another finding is that the costs of debt spikes depend on initial debt levels. Figure 4 shows the interaction between debt levels and debt spikes. In LAC, when debt levels are low, average GDP growth is 3.5 percent. Growth falls to an average of 1.8 percent in period with debt spikes. Similarly, when debt levels are high, the growth rate falls from 1.8 percent in periods without debts spikes to zero in periods with spikes.

Figure 4. Economic Growth vs Growth Debt (% GDP), 1980-2021

Figure 4 shows the change in average economic growth by debt levels and debt spike episodes. IDB estimates based on WEO-IMF. Median gross debt (p50) is 43.5 percent of GDP.

Conclusion: How to Prevent Debt from Huting Economic Growth

Public debt can be a double-edged sword, potentially driving growth or, when mismanaged, resulting in stagnation or decline. Our research shows that several factors influence the effects of public debt on growth. Our flagship study finds that debt levels matter, institutional quality is key, and that debt spikes are risky.

These findings suggest that countries in the region should make progress in different fronts to ensure that debt does not hurt growth. First, countries should continue their current fiscal consolidation efforts, to bring debt to more prudent levels. This is particularly important in the case of highly indebted countries.

Second, government should promote key reforms to strengthen fiscal institutions, to make sure that the financial resources obtained through debt are responsibly spent. Third, governments should adopt robust debt management strategies that mitigate the risk of sudden debt spikes. Achieving these goals will go a long way in promoting the use of debt as an instrument for sustainable development.

Download our publication: Dealing with Debt

Related Blogs

- How Do Inflation Shocks Affect Public Debt Dynamics?

- Are Latin American and Caribbean Countries Complying with Their Fiscal Rules?

- Latin American and Caribbean countries must adopt a pro-growth fiscal strategy to avoid falling into a debt trap

nice article.thanks