The COVID-19 pandemic had a very large impact on government finances. As governments saw their revenues reduced and their expenditures increased to cope with the health and social emergencies, the public debt rapidly mounted. By the end of 2020, the debt-to-GDP ratios had increased by 10 percentage points (pp) compared to pre pandemic levels in the average emerging economies.

The large surges in indebtedness increased pressures for governments to reduce their debt-to-GDP ratios to lower the risks of fiscal unsustainability. Governments have several policy options to achieve these goals. Some of these options include: (i) austere fiscal policy, which reduces the need for new borrowing, (ii) more rapid economic growth, which help reducing the relative burden of the debt, and (iii) defaulting, following a restructuring process.

Another policy option that can help countries reducing their debt-to-GDP ratio is inflation, as it increases nominal GDP. This option is currently of particular importance, as inflation has been high, surpassing 15% in most emerging markets and reaching the highest average levels in the last 25 years in advanced economies. However, it is not always the case that higher inflation dilutes debt. In this blog, we discuss how debt dynamics vary when inflation shocks are either demand or supply driven. This discussion is based on a recent paper of ours, where we analyze how inflation shocks and public debt dynamics.

The Impact of Inflation on Debt Levels Depends on the Type of Shocks

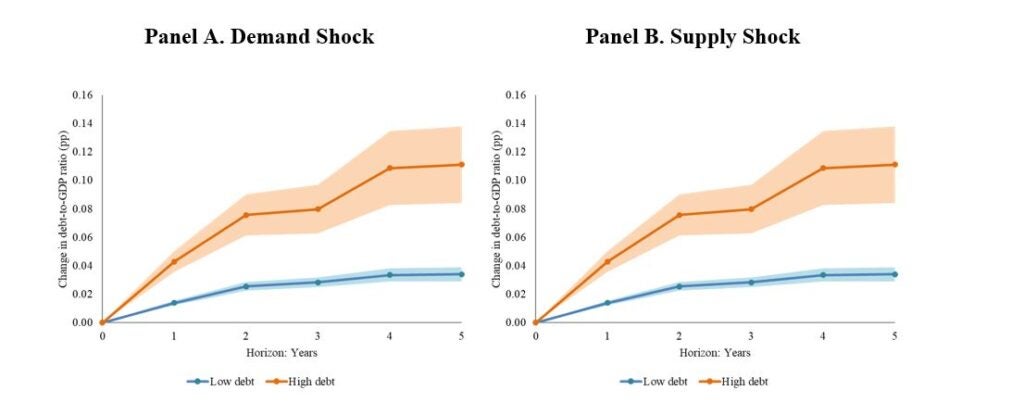

Inflation shocks have very different effects on debt dynamics depending on whether they are supply or demand driven. In our research we found that supply-driven inflation shocks tend to lead to increases in government debt while demand-driven inflation shocks tend to lead to decreases in government debt. We also found two other important features, which are reflected in Figure 1. The first feature is that the magnitudes of the effects of inflation on debt depend on existing debt levels. Higher debt levels amplify the reduction of debt levels in the case of demand driven inflation shocks. They also amplify the increase of debt levels in the case of supply-driven inflation shocks.

The second feature that we find is that the effect of inflation shocks is highly persistent. Even five years after the initial increase in inflation, the effects on debt-to-GDP ratios remain statistically significant. These findings manifest the important long-term consequences of inflation shocks on a country’s fiscal position.

Figure 1. Inflation shock and Change in the GDP Ratio

Note: Figures 1 shows the impact on public debt of a 1 pp inflation deviation from its long run. High debt corresponds to debt above 75th percentile of the sample (70% of GDP). Low debt corresponds to debt below 25th percentile of the sample (30% of GDP). Shaded areas indicate 90% confidence intervals. Source: Valencia, Gamboa-Arbeláez y Sánchez (2023).

The Transmission Mechanisms

The different debt dynamics reflected in Figure 1 are the result of the different transmission mechanisms through which inflation shocks affect key macroeconomic variables. Three important variables worth highlighting are borrowing costs, primary balances, and exchange rates.

The Effects of Inflation on Borrowing Costs

Demand and supply-driven inflation shocks have different effects on government borrowing costs. Supply-driven inflation shocks tend to be associated with a tightening of financing conditions. This is in tern reflected in increases in borrowing costs. In contrast, demand-driven inflation shocks tend to be associated with improved financing conditions, resulting in easier access to credit and lower credit costs.

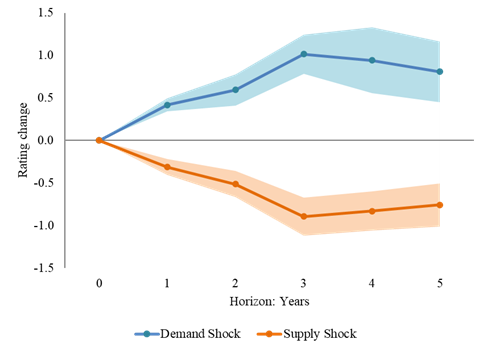

We also analyze the effect on the credit ratings for countries. The results, shown in Figure 2, indicate that a supply shock decreases credit ratings. In contrast, demand shocks seem to improve credit ratings.

Figure 2 Inflation Shocks and Change in Credit Rating

Note: Figure 2 shows the impact on credit rating of a 1 pp inflation deviation from its long run. Shaded areas indicate 90% confidence intervals. Source: Valencia, Gamboa-Arbeláez y Sánchez (2023).

The Effects of Inflation on Primary Balance

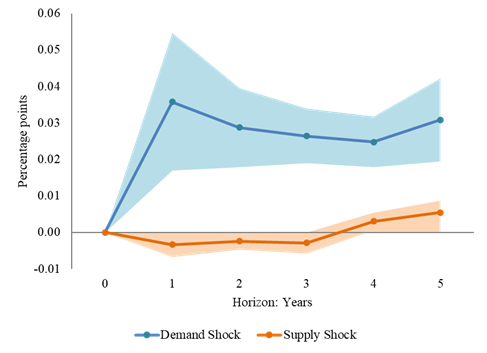

The impact on the primary balance, which reflects the government’s ability to generate surpluses or reduce deficits, also differs between demand and supply shocks. Our analysis reveals that demand shocks have a significant and positive influence on the primary balance. Following a demand shock, there is a substantial improvement in the primary balance, persisting for at least five years (see Figure 3). This indicates that demand shocks play a pivotal role in shaping the government’s budgetary position, allowing for surplus generation and deficit reduction.

In contrast, there is no significant impact of inflation on the primary balance when the inflation shock is supply driven.

Figure 3 Inflation Shocks and Primary Balances

Note: Figure 3 shows the impact on primary balances of a 1 pp inflation deviation from its long run. Shaded areas indicate 90% confidence intervals. Source: Valencia, Gamboa-Arbeláez y Sánchez (2023).

The Effects of Inflation on Exchange Rates

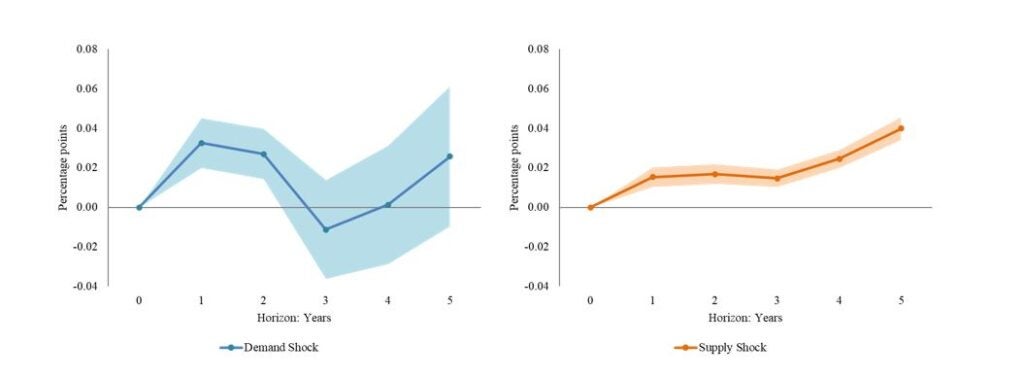

Demand and supply shocks have a significant and positive impact on exchange rates. However, the duration of these effects varies between the two types of shocks (see Figure 4). Demand shocks exhibit a diminishing influence on the exchange rate within a two-year timeframe. In contrast, supply shocks have a more persistent effect on the exchange rate. This implies that supply shocks can lead to a more prolonged increase in the debt burden compared to demand shocks.

Figure 4. Inflation Shocks and Exchange Rates

Note: Figure 4 shows the impact on exchange rate of a 1 pp inflation deviation from its long run. Shaded areas indicate 90% confidence intervals. Source: Valencia, Gamboa-Arbeláez y Sánchez (2023).

Policy Implications and Recommendations

The insights presented above indicate that understanding the root cause of inflation is crucial for formulating appropriate fiscal measures and debt management strategies that ensure sustainable debt levels and promote overall economic stability. It is key for policymakers to differentiate their response to inflation based on the underlying shock. If inflation is primarily driven by supply shocks, a cautious approach is warranted, as these shocks have a more persistent impact on debt. On the other hand, demand shocks present an opportunity for debt reduction through the dilution of debt’s real value. Policymakers should consider this distinction when formulating inflation targeting policies and debt management strategies.

Close coordination between monetary and fiscal authorities is also critical for enhancing the effectiveness of policy measures. Aligning monetary policy actions with fiscal measures can help mitigate the negative consequences of supply shocks on debt dynamics. This coordination may involve adjustments to interest rates or the adoption of joint fiscal-monetary strategies that consider the implications of supply shocks on borrowing costs and debt sustainability.

Learn more about how the IDB works with its member countries on macro fiscal management.

Related articles

Are Latin American and Caribbean Countries Complying with Their Fiscal Rules?

The Fiscal Puzzle of the Ukraine War for Latin America and the Caribbean

Related Studies

Debt Erosion: Asymmetric Response to Demand and Supply Shocks

Dealing with Debt: Less Risk for More Growth in Latin America and the Caribbean

Superb article! There is a typo in “lead to increases in government” the word debt is missing. Thank you very much

Thank you so much for catching it! The missing word had been added. Cheers,