Over the past two decades, a growing number of Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries began adopting fiscal rules to limit overspending influenced by election cycles, public pressure, and other political economy factors, helping the region strengthen its fiscal solvency and sustainability.

However, in recent years the region has suffered several external shocks that have put such rules to the test. The most recent episode related to the COVID-19 pandemic has forced countries to invoke escape clauses to such rules to deal with the health emergency and that has led to large budget deficits and a significant increase in debt levels. As their economies reopened, several countries now are seeking to adjust their fiscal commitments to control spending, ensure sustainable growth and regain investor confidence they will be able to pay off their debts.

To achieve the best outcome in adjusting their fiscal commitments, governments in the region must first consider to what extent the initially established framework has contributed to this purpose, what has worked, and what has not.

In this blog, we summarize the findings of our latest Working Paper Numerical Compliance with Fiscal Rules in Latin America and the Caribbean, which discusses how such rules have performed in the region through the development of a numerical compliance index that we will explain in the following paragraphs.

What Are Fiscal Rules and How Can We Measure Compliance?

Fiscal rules allow governments to anchor their fiscal policies on certain numerical indicators related to budget or macroeconomic aggregates, which end up working as a constraint on spending that would be otherwise influenced by distorted incentives, including common-pool and primary agent problems.

In practical terms, such rules help governments avoid overspending in good times, so they have enough cushion to deal with bad times, reducing the risk their finances fall into disarray and debt levels become unsustainable. When designing these rules, governments also include escape clauses and clear procedures to invoke them to gain fiscal space to deal with unexpected economic shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, for example.

Understanding the performance of fiscal rules in LAC countries has been complicated given the high heterogeneity across countries. In turn, fiscal rules are often immersed in bigger institutional frameworks that consider the sustainability of public debt and other operational procedures for the conduction of fiscal policy.

One way to have comparable data across countries is to monitor numerical compliance with the rules. In turn, we can calculate compliance rates across countries and rules to understand how fiscal rules in the region have worked over the years.

Defining Compliance to Fiscal Rules

To characterize the performance of fiscal rules in the region, we created a dataset with information on whether and how countries have complied or deviated from the implemented rules. Numerical compliance is obtained by contrasting the objectives or targets set by the rules and their executed or observed values. The approach is to compute compliance rates using as much information as possible from official sources of each country, such as the Ministry of the Economy, Central Banks, etc.

However, to understand what is behind the definition of a target and its (non)compliance, we also gathered information about the institutional frameworks of each rule. Since most rules were introduced on a statutory basis with Fiscal Responsibility Laws, the design of the rule described in each law provides information about the macroeconomic aggregate it seeks to constrain, the numerical target or the procedure to set it, as well as escape clauses (if any) and the level of government it covers. Unlike a supranational rule, LAC countries can reform the law that introduces the rule. We also delve into the changes introduced in the laws over the years to identify modifications in the targets or a definitive rule suspension.

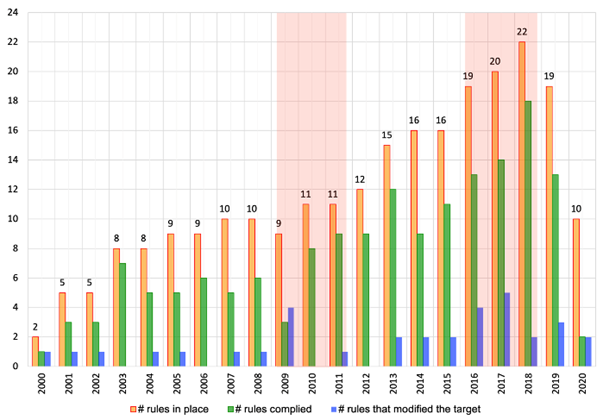

The Figure 1 below shows the evolution of the implementation of fiscal rules, the number of compliant rules in each period, and the number of rules whose target was modified during the year between 2000 and 2020.

In 2000, only two countries had implemented fiscal rules. However, this number increased significantly after the global financial crisis as several countries in the region started to adopt fiscal rules as part of their fiscal policy tools. In 2020, we observed a drop in the number of rules under compliance as several countries decided to suspend their fiscal rules or invoke escape clauses. These procedures allowed them to modify the numerical objectives set in these rules, causing a severe drop in the number of complied rules.

Figure 1: Evolution of Compliance Rate for Latin American and Caribbean Countries

Figure 1 also shows that countries intensified modifications in the rules during other periods of crisis to ensure “compliance”. For example, during the global financial crisis (the period between 2009 and 2011 that is highlighted in red in the graph), the compliance rate dropped significantly in 2009, the same year there was a spike in modifications of the rules to allow compliance rates to rise in subsequent years. Modifications to the rules also accelerated during the end of the commodity cycle between 2016 and 2018 (also highlighted in red), allowing countries to remain “compliant”.

Average Compliance Rates

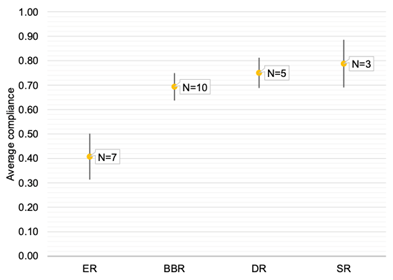

Figure 2 shows average compliance levels of LAC countries for the different rules implemented. On one hand, the structural balance rule (SR) is the highest and stands at 79%. In contrast, the expenditure rule (ER) has the lowest compliance rate, standing at 41%, which is counterintuitive because this rule is usually easy to implement and monitor, which would make easier for governments to comply. This result may reflect some problems in its design, such as the inflexibility of spending in various countries of the region or the variables used as ceilings such as inflation or GDP. The fiscal balance (BBR) and debt rules (DR) also present high compliance rates, 69%, and 75%, respectively.

Figure 2. Compliance Rate by Type of Rule for LAC Countries (Average 2000-2020)

Note: the lines indicate a 95% confidence interval for sample average, and black dots are sample average. ER stands for expenditure rule, BBR for fiscal balance rule, DR for debt rule, and SR for structural balance rule.

An Adjusted Index of Compliance

The data collection process revealed that LAC countries still have room for discretion even when they subject their fiscal policy to rules, which may lead to a shortfall or overestimation of the compliance rates. This happens mainly because:

- Some rules allow governments to exclude certain metrics from the target. Moreover, these exclusions are not always clearly specified or reported, paving the way for misleading results.

- Many rules are not binding in practice. Usually most of these rules must be included in the national budget or in the medium-term fiscal frameworks that are presented to the legislative bodies in each country but, in some cases, countries admit changes or adjustments in the objective established each year, adding to the discretionary power that the rules seek to constrain.

- The rules lack specific sanctions for non-compliance (i.e., deviation from the target). The rules often indicate governments must only present a report explaining the reasons why they failed to comply with a rule or meet a certain target. These rules do not mandate governments to include a detailed plan to correct the course of action to meet the targets. Often, scenarios of non-compliance are mentioned in the law when the rule design includes an escape clause.

To address the problems coming from these situations and avoid the overestimation of the compliance rates, we built a compliance index that considers different elements that add degrees of discretion to implementing the rule.

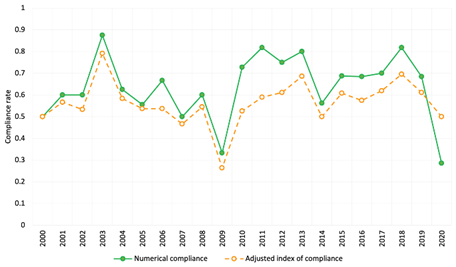

We find that the numerical compliance rates of each country are likely to be overestimated once we account for discretionary actions. Figure 3. shows the evolution of the numerical compliance rate and the adjusted compliance index between 2000 and 2020. When comparing the average rates for the period, we find that the average rate of adjusted compliance drops almost 10pp and stands at 57%. We also observe that the compliance rate is lower each year when we account for discretionary actions in implementing the fiscal rules.

Figure 3. Adjusted Compliance Rate with Fiscal Rules in LAC countries (2000-2020)

Regarding the average adjusted compliance rate of LAC countries with each type of rule separately, we find the same outcome: in each case: the adjusted compliance rate is lower than the one without the adjustment. Notably, we observe a severe drop in the expenditure rule, which stands at 31% against 41% in the non-adjusted numerical compliance rate.

This result reflects that, although expenditure rules are easy to communicate and monitor, they are also the rules where there is a high level of discretion. Similarly, in the face of an unexpected shock, such as the one generated by the COVID-19 pandemic, increases in public spending are easy to communicate and justify. Consequently, it is the rule whose objectives are modified and that is suspended most frequently.

Conclusion: There is Still Too Much Room for Discretion in Fiscal Rules

Our study shows that Latin America and the Caribbean are still not reaping the full benefits of fiscal rules to strengthen discipline, transparency, and macroeconomic stability. There is still too much room for discretion that allows governments to ultimately go around the rules and deviate from the objectives more than they should.

In terms of design, it is essential for governments to balance measures to make fiscal rules flexible without falling into the trap of making them toothless. A certain level of flexibility is important to deal with unexpected shocks. Still, the sum of small actions can quickly turn flexibility into discretionary space. For this reason, the institutional aspect of the rules is fundamental to overall compliance. With increased transparency, the line between flexibility and discretion becomes more explicit, and the message of implementing and complying with the rule becomes more piercing.

In terms of implementation, operational decentralization of rules should be considered. It is not wise to have the same government that designs the target implementing it and monitoring it. Greater oversight is needed. At this stage, the role of fiscal councils are essential. Given their technical nature, they are in the best position to evaluate the methodologies, assumptions, and indicators used in the design of objectives established in the rules.

Download our Working Paper: Numerical Compliance with Fiscal Rules in Latin America and the Caribbean

Learn more about the IDB’s work on macro fiscal management.

Related Blogs

The Fiscal Puzzle of the Ukraine War for Latin America and the Caribbean

How Fiscal Rules Can Reduce Sovereign Debt Default Risk

Leave a Reply