Este artículo está también disponible en / This post is also available in: Spanish

Migrating to cities does not always bring greater opportunities, at least not for indigenous women. Their transfer from rural to urban areas marks in them a triple condition of vulnerability: being women, being indigenous and being migrants. Racial discrimination, unequal access to decent work or basic public services, as well as residence in informal settlements vulnerable to natural disasters, characterize the lives of urban indigenous women in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC).

For this reason, in commemoration of the “International Day of Indigenous Women”, that is celebrated every September 5, we will share some basic data and good practices related to equal access and the empowerment of indigenous women in LAC cities.

What are the problems that indigenous women face in cities?

The presence of indigenous women in urban areas is a generalized fact in the region. In countries such as Mexico, Peru and Uruguay, there is a high percentage of indigenous women who reside in urban areas (54.1%, 56.1% and 97.4% respectively). In contrast, according to ECLAC data in countries such as Colombia (77.8%), Ecuador (79%), and Panama (76.4%), indigenous women are more concentrated in rural areas.

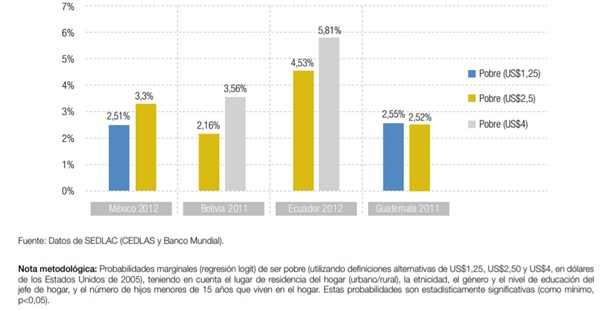

It is estimated that around 23 million indigenous women in Latin America face situations of inequality, persistent gender gaps and discrimination. According to the 2020 Report of Convention No. 169 on indigenous and tribal peoples of the International Labor Organization (ILO), signed by 15 LAC countries, more than 85% of indigenous women depend on the informal economy (mostly domestic workers without social protection) and 7% of them live on less than $ 2 a day. For example, households headed by an indigenous woman are 6% more likely to be poor in Ecuador and 4% more likely in Bolivia (see graph below).

Increased probability that the indigenous household is poor if headed by a woman

Similarly, indigenous women living in urban areas have less access to housing titles, live in overcrowded conditions and are more likely to lack basic services. For example, in services such as sanitation and electricity, their access is 15% and 18% lower, respectively, than that of others in the region.

Likewise, according to the data from UN Habitat, indigenous families that migrate to cities tend to renounce their traditional and culturally adapted homes. In this sense, it is interesting to mention that much of the indigenous ancestral knowledge in terms of housing, materials or construction technologies could contribute to the adaptation or mitigation of the effects of climate change in many of our cities. The power to rescue it and apply it is still a pending issue.

They are not just “vulnerable people” but valuable agents of action

The first step to overcome racial discrimination and gender inequality suffered by indigenous women is the duty of States and citizens to recognize them as full citizens, that are subject to rights and key economic actors in the economic recovery of our cities.

It is also essential to change the perception of them as simply “vulnerable women” and to move to a vision of “women holders of rights”, recognizing their rights and capacities to actively participate in the design of public policies.

Building fairer cities for indigenous women: Good practices from the region

To develop cities that promote equal access for indigenous women, it is advisable to carry out strategies that adapt, prioritize, train, or empower this population. To achieve this goal, let’s explore some of the good practices in the region:

- Adaptation of urban services to the needs of the indigenous population.

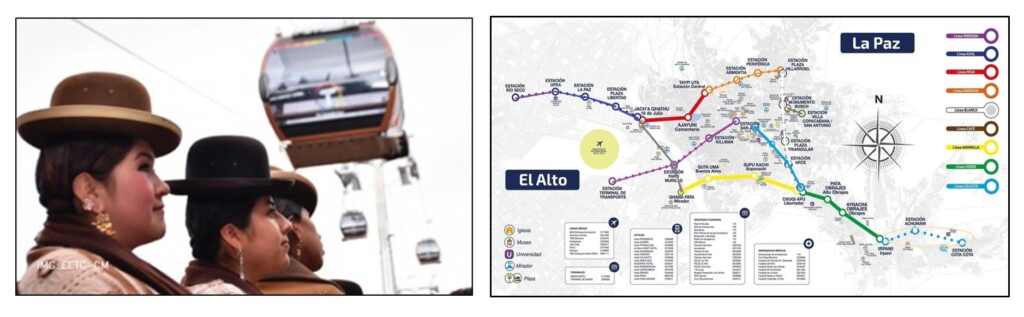

Bolivia’s 30-kilometer-long Mi Teleferico (My Cable Car) connects with the city-run bus service, Pumakatari, in response to the mobility needs of the indigenous population and people with disabilities. “Mi Teleférico” connects the city of El Alto of 922 thousand inhabitants, which is located in the Bolivian highlands, with La Paz, a city of 767 thousand inhabitants. Most of the residents of El Alto belong to the Aymara indigenous ethnic group, so the names of the stations have been adapted to their language. The use of this service saves about 22% of travel time and an average net benefit for the passenger of 0.58 USD, with respect to the situation prior to the existence of these means of transport.

- Empower financially through training.

The program “Acceleration in electronic commerce for women artisans” designed in conjunction with the Ministry of Culture of Panama, supported the contracting of consultancies for training in electronic commerce for 60 indigenous women artisans. The program ended in November 2020, which included 4 training workshops and mentoring on the topics of “Architecture of Collections for Digital Markets”, “Good Practices for Digital Publications” and “Identity Story”.

- Adequate housing subsidy prioritization.

The “Program for the Integration of Vulnerable Neighborhoods” (2021) designed in conjunction with the Program of Camps of Chile, aims to improve urban integration and habitability of national homes and migrant resident camps. It will prioritize housing subsidies for indigenous people, many of them female heads of households, who live in these informal settlements. According to the 2017 census, in the urban areas of Metropolitana (30.1%), Araucanía (19.6%) and Los Lagos (13.1%) they are comprised of the highest concentration of indigenous population residing in Chilean camps.

The Social Interest Housing Program (2006) developed in the municipality of Lepaterique, in the peri-urban area of Tegucigalpa, Honduras, was a subsidy program to finance self-built housing, in which a group of women learned techniques of construction. Later, they moved to different municipalities to teach other women how to build their homes. Around 10,500 houses have been built, all made by women, many of them of indigenous origin. Here is a video of the program:

Towards an inclusive, sustainable, and fair future

A city moves in the right direction when it removes barriers for the most vulnerable people and creates opportunities and environments that are culturally adapted to the needs of its inhabitants. While this effort to remove barriers should be seen as a right, it can also be applied to benefit our cities. Having sustainable cities, with identity and based on gender equality will benefit us all.

What else can be done to achieve quality sustainable cities? Let us know your comments!

Leave a Reply