Este artículo está también disponible en / This post is also available in: Spanish

Most cities need financing to carry out their urban development projects and programs. Having adequate financial resources is not always easy. For this reason, from the Housing and Urban Development Division of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) we thrive to facilitate the access to, and knowledge of, the most innovative financing strategies and instruments to cities of Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC).

As part of our efforts to achieve this goal, the IDB Cities Network organized its annual Mayors Forum in the city of Denver on April 26th. Under the motto “Financing for the sustainable development of cities“, the IDB brought together nearly forty mayors from LAC to strengthen the leadership of cities in the region in access to financing through the exchange of knowledge and experiences.

As we mentioned in the first blog post of this series, public-private partnerships (PPPs) can be a very beneficial way to access financing from the private sector. Although this type of association continues to be a marginal source of financing in the cities of the region, countries like the United States offer examples of success stories that are worth sharing. Don’t miss this blog post, and find out how the city of Washington, D.C. managed to build a metro station through public-private partnerships, generating a large amount of wealth by the recovery of land value gains.

An APP with a common goal: the revitalization of NoMa, a neighborhood in decline

Although located close to the city’s downtown, NoMa (‘North of Massachusetts Avenue’) was in the 90s a neighborhood composed of empty railway cargo yards, abandoned buildings, warehouses, and vacant lots. According to a WMATA study conducted in 1999, 5,600 people were living on that area an average income of $23,396. Also, 24% of residents lived in poverty and 50% didn’t own a car, meaning there was an increased need for public transit alternatives.

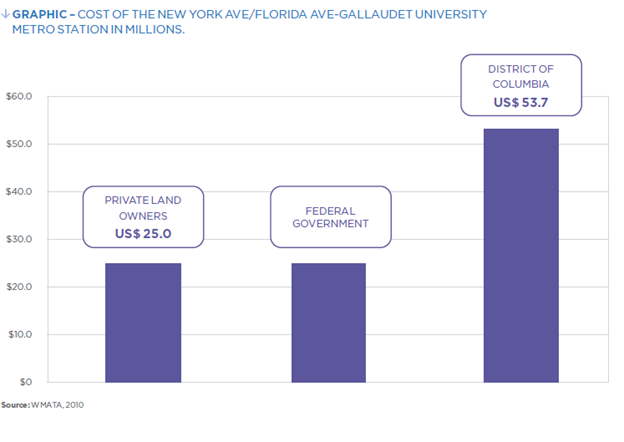

To reactivate this neighborhood, and as part of a general economic revitalization plan of the Washington DC mayor’s office, it was decided to build a subway station that would serve as the first step in turning NoMa into one of the most prosperous areas of the city. However, Washington, D.C.’s municipal finances in the late 1990s were not at their best moment. Therefore, it was decided to seek external financial assistance, specifically from the private sector. The project was subsequently built via a single public-private partnership, combining funds from private landowners (see graph and box below), the District of Columbia, and the federal government. Each party initially agreed to pay $25 million (or a third of the total costs), with the District of Columbia responsible for any surplus costs.

What makes the construction of this metro station special?

The NoMa station is the first Metrorail station to be built with a combination of public and private funds. The expected project cost for its construction was over $75 million (ultimately exceeding $100 million).

The Task Force (TF) received $350,000 from the city to produce a feasibility study that examined the economic opportunities and benefits potentially arising from a new metro station at the intersection of New York and Florida Avenues, thus connecting the NoMa neighborhood with the Metrorail network and the region more generally. The study predicted that investing in the station could create 5,000 new jobs and attract $1 billion in investments and development.

Work on the station began in late 2000 and was concluded by November 2004. Developers started showing interest in lots in the NoMa area even before the District’s approval of the final plan, launching a virtuous economic cycle that has lasted nearly two decades.

Results of the public-private partnership in the NoMa neighborhood

This PPP more than met to regenerate the NoMa neighborhood and make it one of the most prosperous in the city:

- Economic Output – $4.7 billion in total economic output was generated from both buildings and jobs across all sectors starting in 2004 ($2.2 billion in cumulative construction output and $2.5 billion in permanent output in 2014).

- Construction Spending – $1.7 billion in direct construction spending, not including improvements to parking lots and infrastructure.

- Labor Earnings – Since 2004, the total labor earnings generated by construction activity have been over $1.1 billion. In 2014, permanent labor earnings amounted to almost $1.9 billion.

- Employment – Approximately 14,338 direct, indirect, and induced jobs were created between 2004 and 2014 as catalyzed by NoMa construction spending. An additional 15,168 permanent jobs were created, resulting in a total impact of 29,506 jobs.

According to the most recent data, “from 2015 to 2019, projected annual municipal revenues (not including one-time revenues such as construction and other permits or certain recurring revenues like parking fees) were estimated to increase from $68 million to $152 annually46. Overall, during the period from to 2006 through 2019, the NoMa Station Impact Study Area was expected to yield nearly $1 billion in total cumulative revenue to the District.”

Three key takeaways from NoMA´s successful experience

- Clear communication of intentions and goals: The long-term plans adopted as part of the project notably allowed for effective coordination of land use and mobility priorities. Yet it is important to note that all levels of government showed a commitment to the region beyond implementing strategic plans themselves; the federal government, for example, agreed to build the headquarters for the Bureau of Alcohol and Firearms in the area, and the District of Columbia took the risk of potential cost overruns upon itself. This offered an additional level of stability to attract private investment more effectively.

- Stakeholder partnerships: The project incorporated a wide array of stakeholders throughout its full lifecycle. This included direct outreach to local community members and close coordination with the private sector. As part of this engagement, local government officials notably communicated the potential value of the project, including the likely land value increases resulting from transit investments. It was further clear, in turn, that transit improvements were only possible through private participation. The result was a greater willingness by the private sector to contribute financially and otherwise to ensure the project’s success.

- Innovative instruments: The special assessment districts that were approved as part of the project offered both an innovative method through which the private sector could contribute financially to the project, while maintaining an interest in its continued success over time, as well as a mechanism for immediate execution of the project through bonds backed by anticipated future revenue from property taxes. This method of land value capture joins an array of institutional innovations (including such organizations as Action29 and the NoMa BID) to make NoMa a model for many subsequent efforts.

We truly hope you have found this article enriching and useful. Next week we will share a new success story in terms of subnational financing. Do not miss it!

Related Content

Leave a Reply