Este artículo está también disponible en / This post is also available in: Spanish

More than a billion people live in informal neighborhoods around the world, also known as slums, barriadas or villas, or favelas in Brazil. These neighborhoods usually lack access to clean water and sanitation systems, and residents live in inadequate and overcrowded housing. In 1995, Favela Bairro (FB) program in Rio de Janeiro Brazil, aimed to connect these informal neighborhoods to the city, by providing and improving services and upgrading infrastructure. FB’s novel approach received wide international acclaim. In 2000 it won Harvard’s Veronica Rudge Green Prize in Urban Design recognizing it as a “project that contributes significantly to the quality of urban life.”[1]

What are the results of the program ten years later?

Did the infrastructure improve the lives of the Favela residents in the long term? A newly released report: Bairro: 10 years later examined the state of the infrastructure of 88 favelas of the Favela-Bairro phase II (FB2) program between 2000 and 2008, and studied the sustainability feasibility of these interventions.

The report is timely due to the renewed concern of sanitary conditions during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemics in informal neighborhoods. A recent study from India found that households living in informal neighborhoods would suffer 44 percent higher chance of transmission of infectious diseases such as the flu ,oppose to those living in other areas. Overcrowding conditions increase infection rates, while malnutrition and the lack of sanitary conditions make it more likely to spread infectious disease. The current state of the program is especially important amid the COVID-19 pandemic and could provide guideline for future interventions.

The research presented in the report used two complementary methodologies carried out in parallel:

- A qualitative study based on focus groups to capture the perception of direct beneficiaries on the upgrades. The main conclusion was that although immediately after the interventions took place, there was a general improvement in resident’s lives (Atuesta and Soares, 2016), over time the infrastructure degraded considerably and public services suffered from, most reverting to the original conditions —similar to those favelas that were not upgraded (control group). Some interviewees complained about sewage overflows, garbage accumulation, electricity fails, and broken public lamps on the streets, among other issues. Half of the residents interviewed expressed positive opinions regarding public transportation infrastructure, however credited this particular result to their own actions —residents repaired some of the potholes by filling them with sand to allow smooth circulation of cars and motorcycles, and reported that the electrical wiring was fixed by them whenever possible.

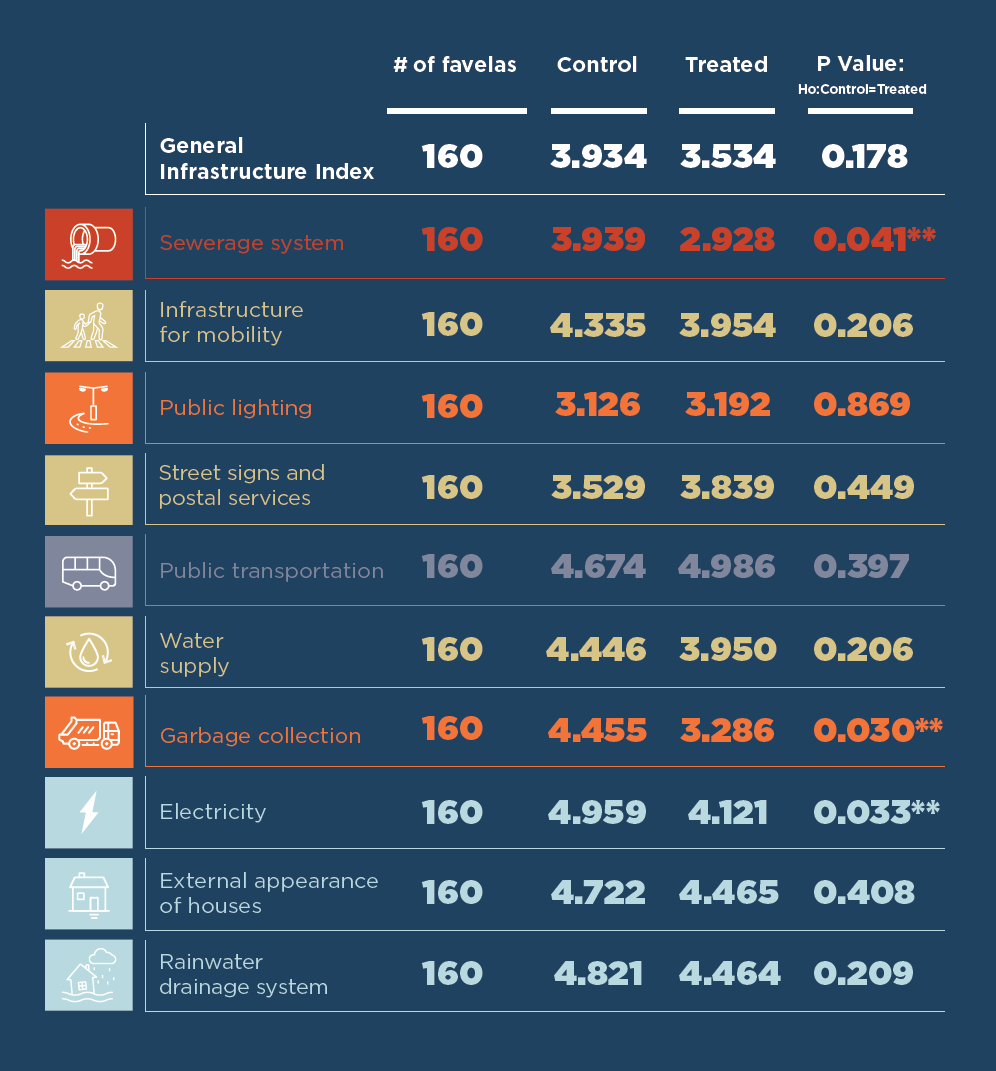

- A standardized analysis of the state of maintenance of the infrastructure in the 88 favelas upgraded by FB II. This formal inspection consisted of a technical examination of the state of the infrastructure. A team of technical experts was sent to visually check and grade the state of maintenance. The results showed that ten years after project completion the group of favelas intervened in the FB program scored the same as the control group. In fact, the treated group had significantly lower scores in three types of infrastructure: the sewerage system, the garbage collection and electricity, vesus the control one. (see Table below)Table Index by Type of Indicator and Treatment Status

Table Index by Type of Indicator and Treatment Status. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Notes: Score: 0 = non-operational; 6 = excellent condition. Level of statistical significance: ***p-value = 0.01, **p‑value = 0.05, *p-value = 0.10. Although we refer to 88 favelas upgraded in FB II, some of these 88 are in complexes or groups linked like a network, meaning that some favelas are a complex of several favelas. Counting each favela individually, there are a total of 160 favelas reported in this table.It was determined that multiple factors could account for the infrastructure deterioration, not necessarily tied to the FB II program; rapid population growth for example: Between 2000 and 2010 the population in Rio’s favelas grew nearly 27 percent, while in the rest of the city it has grown just 3.4 percent.[2]

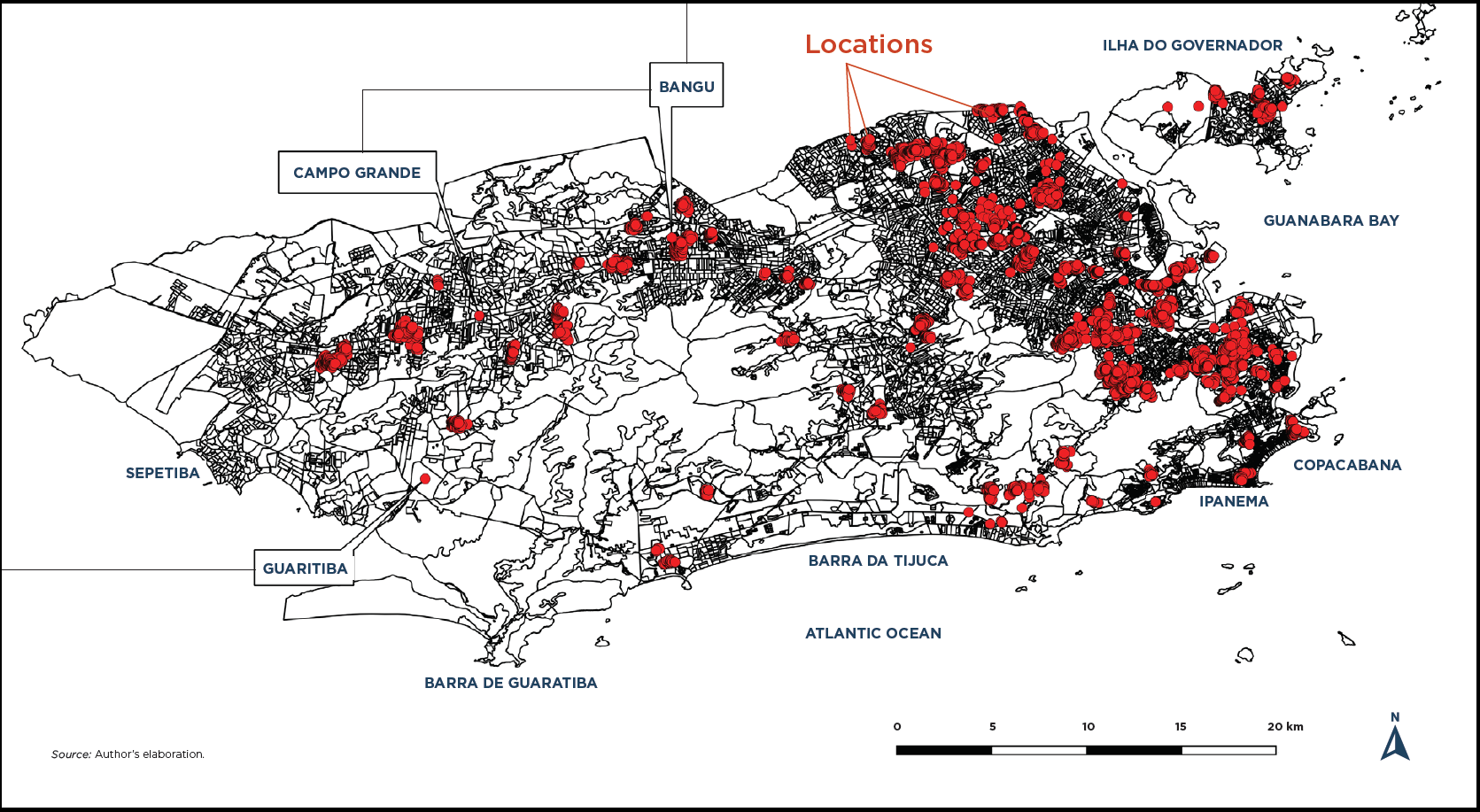

Favela Bairro II. (2000–2008) Locations. Source: Authors’ elaboration. Although insufficient maintenance and follow up could be the cause of the negative results, vandalism and steep topography should also be considered: Engineers who work in these locations observed gangs frequently braking public lighting -making it easier for them to hide authorities. It was noted that drug related gangs made potholes (see Images) or build barriers in the streets or barricades that hinder the entrance of police cars and rival gangs. Also, these groups destroy internal mobility structures, such as public stairs and ramps, for more effective hideouts.

Image. Intentional Roadblocks in Favela Morro da Quitanda in Rio de Janeiro, 2018. Source: Overview Pesquisa.

Lessons to be learned

Design for endurance can be accomplished with the choice of better materials and layouts that require minimum maintenance and recurrent expenditure should be budgeted for repairs on a regular basis; extra resources should be allocated to hilly and densely populated areas. For better outcomes, it is key to involve and educate residents on the preservation of the interventions, and recognizing that these type of projects are likely to attract more people, increasing demand on the built infrastructure. It is important to understand that built interventions might not be sustainable in neighborhoods that face chronic local violence or where there is a notable absence of authorities and government, making long term durability possible, only by constant action from all stakeholders.

Read the blog in portuguese.

Guest Author: Janice Perlman Dr. Perlman is a research scholar, author, public speaker and urban policy consultant. Her most recent book, Favela: Four Decades of Living on the Edge in Rio de Janeiro (OUP, 2010), traces the life histories of hundreds of urban migrants over four generations. It is a follow-up to her seminal book, The Myth of Marginality (UC Press, 1976). She is currently finishing research on Mega- Events, Public Policies and the Future of Favelas Cariocas. The book titled “The Importance of Being Gente” will complete the Favela Trilogy. Her Awards include Guggenheim Award; C. Wright Mills Award; Chester Rapkin Award; two Fulbrights and the Publishers PROSE Award for “Outstanding Contribution to the field of Social Science. She is President of The Mega-Cities Project, a global non-profit designed to “shorten the lag time between ideas and implementation in urban problem solving”. Now in its 30th year, it is supporting/awarding young urban leaders as in its new initiative, MC2. She was a tenured Professor of City and Regional Planning at UC Berkeley and has taught at Columbia, NYU, Trinity College and UFRJ. She directed Strategic Planning at The NYC Partnership; Science, Technology and Public Policy at the NY Academy of Sciences; and the Neighborhoods Task Force of the National Urban Policy.

[1] For more information about this prize, see https://urbandesignprize.gsd.harvard.edu/.

[2] Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics IBGE.

Leave a Reply