Many countries have used natural resources extraction to realize energy independence, as well as strong economic and social outcomes. However, for every success story there are sobering lessons for new producers, such as Guyana. Lessons premised on the principles of proactive and coherent petroleum sector governance, inclusive policy formulation, and social accountability.

In 2015, a consortium of three major oil companies made an offshore oil discovery (Liza-1) that is set to irrevocably change the development trajectory of Guyana. For a small economy, with a per capita GDP of $5,000, the hopes are high that this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity could transform one of the poorest countries in Latin America into one of the richest.

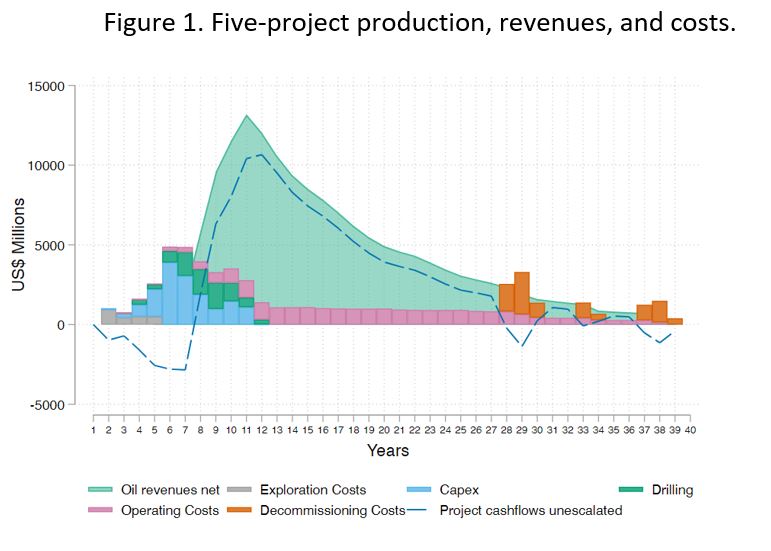

Liza 1 and other projects would raise the country’s oil output to 750,000 barrels per day (bpd) by 2025. Considering the sequencing of the targeted five projects by 2025, the expected windfall for the government progressively increases. Our most recent study: Traversing a Slippery Slope: Guyana’s Oil Opportunity estimates that in 2025, Guyana would earn a projected US $ 2.8 billion in oil revenues as part of its government revenues, which would ultimately accumulate to US$49 billion by 2054. Guyana’s offshore fields are estimated to hold more than 8 billion barrels of oil equivalent after 20 discoveries and are expected to place Guyana among the largest oil producers in the region.

With new-found wealth, the challenge is staving off the natural resource curse (NRC) – accelerated loss of competitiveness of non-oil sectors and an inability to translate natural resource rents into improved social and economic realities. The reality is that most countries that experience a natural resource windfall seem unable to harness this for long-term, sustainable economic development and reduced inequality.

Guyana is an ideal case when assessing the relationship of institutions given its nascency to hydrocarbon development, and the enviable opportunity to avoid the catastrophic pitfalls of other resource-rich, yet underdeveloped countries.

Many scholars have recently revisited the role of institutions and NRC. They have examined how weak institutional frameworks and underlying legislations, when coupled with commodity price volatility have been linked to adverse outcomes. These include poor economic performance, slower (or no) progress towards economic and energy diversification, reduced transparency, increased rent-seeking behavior and patronage politics. In other more extreme cases, it may lead to violent conflict over equitable distribution of resources, or a deterioration of democratic norms.

The challenges of building government institutions are well known. A central theme in much of the literature on development is the importance of capacity building, particularly to equip countries new to oil, gas, or mining development for the specialized tasks of oversight.

For Guyana, provisioning the scale of financial and technical resources required to develop institutional capacities and the legal framework to optimally administer the petroleum sector is a dynamic challenge given the changing domestic needs. The multifaceted approach required for marshalling the cadre of interrelated institutions is extensive since strengthening efforts should not only focus on subject ministries or agencies but sister agencies that operate along the value chain or can influence decisions though overlapping legislations.

Institutions with regulatory roles — such as the Environmental Protection Agency and Guyana Geology and Mines Commission, and those with policymaking responsibilities, such as the Department of Energy — may consider a combination of interventions to bridge technical gaps.

Following the experience of other jurisdictions, oil discovery was immediately followed by targeted actions by governments to first embed experienced industry experts – geophysicists, petroleum engineers – within key agencies to overcome the knowledge asymmetry enjoyed by IOCs. Secondly, these countries invested heavily in the education of their citizens along every aspect of the petroleum sector overseas, where upon return, the newly qualified citizens can effectively shadow those embedded industry experts. This allowed for rapid knowledge transfer through learning-by-doing, while the risks of errors and less optimal decisions were negated or reduced.

In essence, decisions have significant impact on the long-term development of the sector and the prosperity of the country, and an outsourcing approach that focuses on on-job knowledge transfer can significantly reduce the learning curve for new producers. Such a model may work in Guyana, but the upfront costs of procuring experienced industry talent and funding the education of Guyanese in targeted professions may prove significant in the short term. However, when viewed as an investment to ensure the expected revenues materialize and reduce value leakages, it may prove a worthwhile investment in the long run. To learn more about this issue, download our publication here.

Leave a Reply