Your government wants to increase gasoline prices. Are you in? If you are like most people, the answer is no. You commute using public transport, or maybe you use your own car. Either way, a gasoline price hike may hurt your budget.

Research conducted at the Inter-American Development Bank shows there could be an affordable way for governments to make you love gasoline price hikes.

While increasing the price of gasoline and other energy sources is an unpopular policy, it may be a necessary one:

- Higher gasoline prices reward the adoption of electric cars, which we will need to drive emissions down to zero and stabilize climate change.

- Higher electricity prices can also help incentivize the adoption of more energy efficient appliances and buildings by private business and households.

- More generally, carbon taxes can help fill the government’s coffers while sending the signal to private markets that they will be rewarded financially to reduce their carbon footprint.

Are you in yet? If not, let me continue explaining. Lessons learned from past successes and failures in increasing energy prices suggest that a few elements are important. One is that governments should acknowledge that there are downsides to energy price hikes and propose policies to compensate those who will be negatively affected. The real question here is: How can governments reconcile public acceptability and efficient price signals?

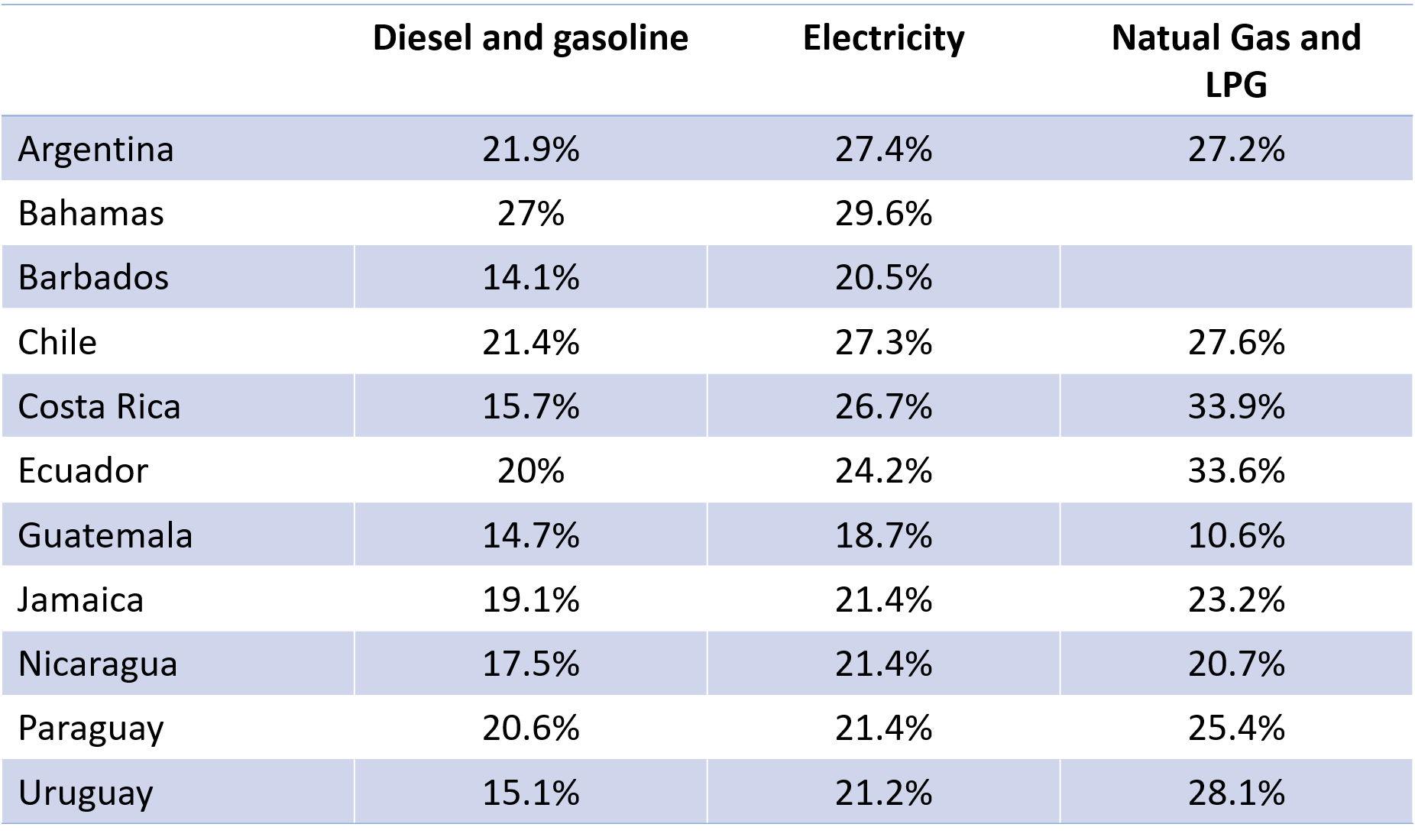

The recently-published study can help governments from Latin America and the Caribbean take steps so that energy price hikes don’t necessarily have negative social consequences. The study shows that one-quarter of the money governments make by raising energy prices is typically enough to compensate poor and vulnerable households for the impact of the reform on their budget. This average masks different national contexts and different usage patterns for different energy types, as shown in the table below.

A small fraction of energy revenues is enough to compensate a sizeable share of the population

The fraction of government proceeds from subsidy removal or energy taxation needed to compensate households in the bottom 40% of the income distribution, for 11 Latin American and Caribbean countries and 3 energy types. Source: Feng at al, (2018), Managing the distributional effects of energy taxes and subsidy removal in Latin America and the Caribbean.

These numbers consider both the direct impact of energy price hikes (how much the utilities and gasoline prices would go up) and the indirect impact (how much the price of other goods and other services would be affected by the prices hikes). We teamed with researchers from the University of Maryland to track, for instance, how much gasoline and diesel is used to transport consumption goods. We then assessed how increasing the price of gasoline would impact the price of those items – it turns out food and public transport are the most important ones for poor households. Similarly, electricity is used in most business, and gas is sometimes used to make electricity. We tracked that too.

The point is that governments can give back part of the proceeds from energy taxes or energy subsidy removal to vulnerable households. The final impact of a tax reform always depends on how the revenue is redistributed. Many options can be used, such as improving access to free healthcare or maintaining the cost of public transport low. One policy that has been used successfully in the Middle East and North Africa is the use of direct cash transfers to poor households. Similar solutions have been used in the region, including in Brazil and Dominican Republic. Expanding the coverage or the amounts delivered by the national cash transfer programs is a promising solution: most countries in LAC have one (from Bolsa Famila in Brazil to Prospera in Mexico), they are generally associated with good development outcomes (from reduced malnourishment to better participation in job markets), and can also help households cope with the consequences of climate change. A win-win.

Read our new publication Managing the distributional effects of energy taxes and subsidy removal in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Leave a Reply