This is the second post on how Scotland used the public health model to curb violence. The first post was published on Nov. 7

By John Carnochan

In six years ending 2013, we cut the homicide rate in Scotland by half, and we used the public health model to do it. In the first post I laid out some of the general principles underpinning this model as it relates to crime fighting. Here I note how we proceeded to implement the model.

The diagnosis

The important thing is to make a clear “diagnosis” of the problem. We used crime data, incident data, ambulance data and intelligence to identify where and when fights were occurring and profiling the violence.

A key part of the diagnosis was identifying the gangs and the gang members, their territories and where they fought and whether they used weapons. We used police crime data including criminal intelligence, reported crime, incident logs, in addition we liaised with local community police, local community groups and youth workers and to build as accurate a picture as possible. We also spoke to the gang members themselves.

We found that many young men were in youth gangs and engaged in recreational fighting. They were very territorial and knives were used in a significant number of assaults, providing a lethal means, so what might otherwise have been a minor assault had the potential to be far more serious or even fatal.

We also identified what diversion facilities were operating in the area sports clubs like football and boxing; we spoke to youth outreach workers and local community leaders. We thought that some of those involved in fighting often did so because they had nothing else to do and they did not attend some of the organised sporting clubs because they feared passing through other gang’s territories.

The focused operation

We ran targeted policing operations focusing officers in particular areas. We increased the level of stop searches targeting the areas where the knife assaults occurred and the specific age groups of those we know from our examination of the data were most likely to carry a knife.

We also briefed all the police officers involved to ensure the stop searches were carried out effectively and not in a way that would alienate the youth. During the searches the police officers spoke to the youth about what they were doing, emphasizing that fighting was unacceptable, it was rejected by the community and there were other things to do. The police were required to record the details of everyone they stopped and searched.

We used hand held metal detectors where appropriate and mobile scanners similar to the scanners used at airports. We used these at train stations and bus stations, anywhere that large numbers of people were passing and where we knew violent offenders frequented. They were used on the routes into the city centre and had a very good deterrent effect.

Coordinating with other key actors

Stop search is a very effective policing tactic. It deters weapon carrying and provides an opportunity to speak to the at risk youth and convey to them an accurate and clear message. The tactic must be carried out as part of a broader more comprehensive violence reduction strategy including the social and community elements I have mentioned. Otherwise it will just alienate the youth and make the job of policing more difficult, creating a “them and us” conflict situation.

We liaised with the local housing authorities and worked with them to reach the parents of the gang members persuading them to encourage their sons to come to football or other clubs and not to fight.

We also worked with prosecutors and courts, informing them of our strategy and why we were doing it. We asked them to prioritise those cases that involved violence and the use of weapons.

Tracking, evaluating and following through

We tracked all the cases that were reported and were able to build an accurate picture of when someone was caught, when the case was submitted, when the prosecutor processed it, when it went to court and what the sentence was. This allowed us to identify any blockages in the processes and ensured that the cases were continually given priority.

We had the facts and figures, which gave us the arguments to change the legislation as well as our own policing policy so that anyone caught carrying a knife was arrested and kept in custody until they appeared at court. They were fingerprinted, photographed and their DNA was taken. When they appeared at court, prosecutors opposed bail and if Bail was granted they asked for conditions to be imposed, these included a curfew or exclusion from a particular area.

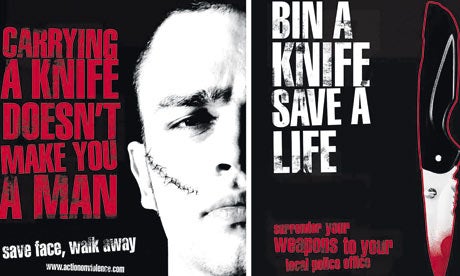

We ran a high profile media campaign about knife crimes, strap lines included “Real Men Don’t Carry Knives” & “Save a life bin the knife”. The media message was that the communities were tired of young men fighting and carrying knives.

We went into schools in the identified areas and spoke of the dangers of knife crime, and we engaged with medical professionals to do this. Community police also reinforced the message.

We made sure the football and other diversionary activities were made available on the days and at the times when our diagnosis identified the gang fights were occurring. We supported activities in the identified areas like football, clubs and basketball. The youth workers who run these activities are trained to engage with the young men and help identify opportunities, such as educational needs, drug or alcohol counseling.

These tactics will reduce violence, particularly as it relates to weapon use, including guns and other lethal devices common in Latin America. It will not on its own stop all violence. It is essential that the policing element is a part of a comprehensive collaboration of services and these must be carefully and effectively coordinated.

John Carnochan is the former Detective Chief Superintendent at the Scottish Violence Reduction Unit. He is currently part of the Public Health Medicine team at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland and continues to work with the VRU.

Leave a Reply