Creating an electronic health record system might at times seem like an impossible undertaking, and it is true that building a successful system is no simple task. Such a system gives physicians access to complete information on patients, including all previous interactions with the health sector, the medications they take, and even socioeconomic factors that may be related to health. It makes patients’ information readily available to them and allows them to decide whether or not to share it with a service provider, as well as to schedule appointments and view test results from their cell phone. Such a system can also warn of possible drug interactions or allergic reactions, help make sure quality protocols are followed, and enable research while keeping information confidential and ensuring consent in its use.

While some countries—including Canada, Estonia, Israel and several others—have had success in implementing electronic health records, our region also offers significant examples of progress that we can learn from. These examples include the city of Bogotá and Uruguay, along with the story of Costa Rica’s EDUS.

What is Costa Rica’s electronic health record system?

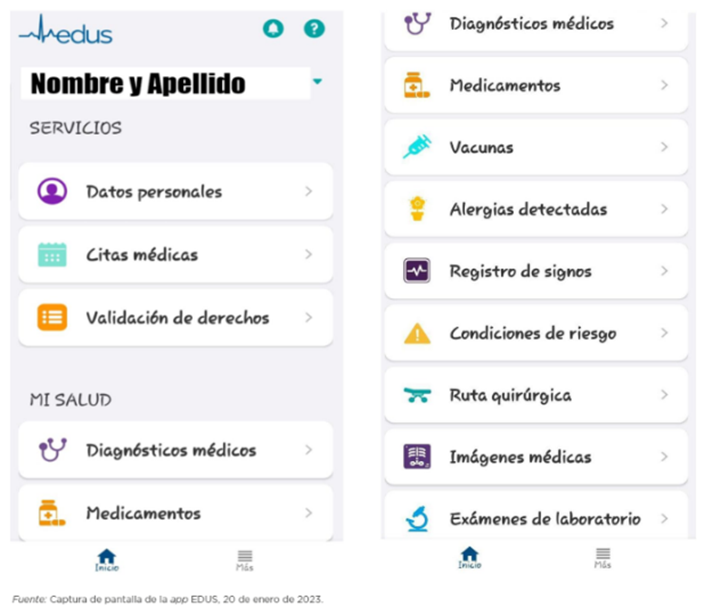

The EDUS system serves approximately 92% of the Costa Rica’s population and features an app that patients can use to schedule services or view test results, among other options.

The EDUS has supported over 63 million healthcare actions. The app has been downloaded over 5 million times and continues to be the top health app in the iOS and Android stores in Costa Rica.

How was Costa Rica able to develop this system?

At the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), we documented the experience of creating the EDUS as part of our digital health case study series. The lessons from this experience align closely with the recommendations in our publication The Golden Opportunity of Digital Health for Latin America and the Caribbean. This post highlights two of the most important lesson from Costa Rica.

Create a nationwide project

The EDUS has been more than 10 years in the making and continues to coalesce. While adjustments were made along the way, the project’s overall direction was set by a law (9162), and the country was able to stay the course for a decade. This is no small feat, as many efforts in the region are undermined by constant changes in management that wear staff down. Structural decisions made at early stages of the EDUS included:

- Developing the system in-house instead of hiring an external firm or purchasing an existing solution;

- Using a centralized data architecture;

- Starting with primary care when rolling out the solution.

For other countries, the best way to handle each of these factors depends on their specific context. For some, the ideal solution might be using a decentralized architecture (as Uruguay has) or licensing an existing solution (as Bogotá chose to do). In fact, for most countries a unified information system is not an option, and they must rely on making different systems interoperable in order to share information. The takeaway from the Costa Rican case is that leaders based their decisions on the country’s unique context and then put those decisions into practice with the backing of legal reforms and with few deviations over the course of a decade.

Treat the creating system as more than just a technology project

To develop a project with other dimensions besides technology, the Infrastructure Management Unit was put in charge of the EDUS. The team responsible for the EDUS is multidisciplinary and includes medical, engineering, nursing, laboratory, and project management professionals. The team also strove to consult all personnel that would eventually use the solution and created a change management plan that involved staff at the different health facilities. These staff members took a leadership role in implementing the EDUS at each establishment, and they were trained in soft skills and leadership and resources for this process.

The EDUS did have its challenges along the way, including little clarity about funding at the outset and, more recently, a cyberattack that did not directly compromise the system’s information but did lead to significant outages and forced a completely unexpected—albeit temporary—return to using paper.

The fact that the EDUS has made it through these and other challenges as it grew is a testament to its solid foundation. This foundation essentially consists of strong legal footing, commitment to a nationwide project, a dedicated multidisciplinary team for the project with a clear mandate, and engagement of the system’s eventual end users.

To learn more about this electronic health record system, see our case study: Costa Rica’s Unified Digital Health Record (EDUS) System: Best practices, history, and implementation

Leave a Reply