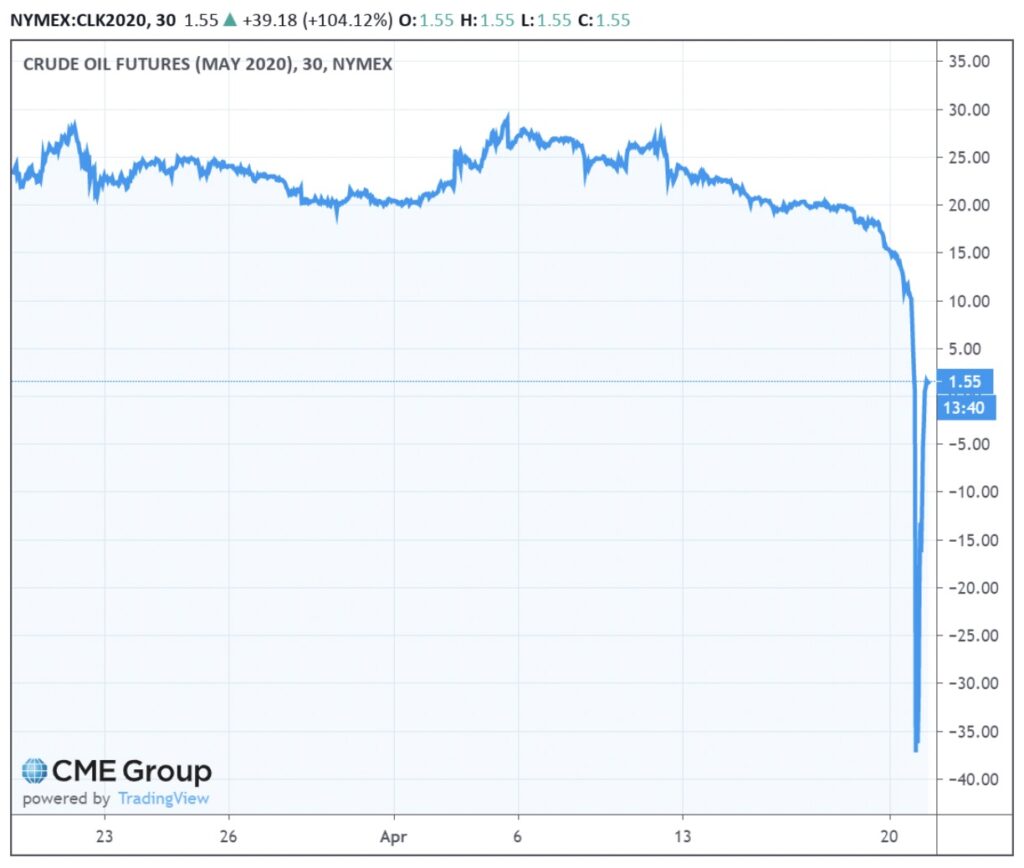

“Oil is at a negative price, -US$37 a barrel.” Those were the headlines on April 20. A negative price for oil? That makes no sense many friends told me.

To understand this, let’s take a few steps back. There are two standard prices for the global oil market. In the United States, a futures market on a blend known as WTI (or West Texas Intermediate) is an important reference price. The other is Brent (named after an oil field in the North Sea) which originated in London and which has now gained more acceptance as a global price for oil. WTI is actually a somewhat sweeter and lighter blend than Brent and many think it should trade at a premium, but that is rarely the case these days.

A curious feature of the WTI futures market is that if you buy oil for delivery in the future (a long position) then you take delivery of that crude in Cushing, Oklahoma. Why Cushing? The small town of 8,000 people is where several major pipelines converge and is home to a set of large storage facilities.

But most people who use this market do not actually take delivery. It is estimated that only 5% of contracts, at most, are left to expire. Even so, billions of barrels of oil are traded each year using WTI futures contracts, which is extremely useful for those who want to take a position on the oil price (either that it will go up or down) or those that need to hedge oil price risks.

But in extreme times, the delivery conditions can be very important. While there is a lot of storage available in Cushing, in the end it is finite. As demand has dropped so much and oil continued to flow down the pipelines to Cushing, that storage filled up.

West Texas Intermediate May 2020 Futures

The May contract actually settled on April 21. So anyone who did not want to actually trade in physical oil had to close out the contract by the end of that day. The standard advice for anyone in that situation is to close out their positions around two weeks before their contracts expire. So why did the May contract end up with a negative price on April 20? The most likely explanation is that traders with no intention of taking physical oil had not closed out their positions or some who had long positions and were planning to take physical delivery realized they could not, as there was nowhere to store the crude oil. The volume traded on April 20 was about 150 million barrels—not an insignificant amount. Those who had to sell, did so at any price. For some, near the end of the day, when liquidity likely dropped, it was less costly to sell at a negative price than to pay to somehow store the oil somewhere else.

West Texas Intermediate June 2020 Futures

The important point here, however, is that a negative price for the WTI May oil futures contract is not a negative price for oil. The June futures contract closed on April 20 at a positive US$20 per barrel and had a volume of about 1 billion barrels of oil that day, much more than that of the May contract. So, for WTI, that was a more representative price. Moreover, Brent closed that day at around US$26 per barrel. The delivery conditions for Brent are very different and much less subject to these very local circumstances. The price of oil is low by any historic standard, but it is not negative. The difference between these reference prices (US$20 for WTI for June and US$26 for Brent), that reflected more closely global market conditions, and the -US$37 for the May WTI futures, was all about the delivery conditions in Oklahoma and the positions that some needed to close.

But there may be further repercussions. As the June WTI contract becomes the nearby (the first futures contract that will expire), its likely liquidity will shift earlier to the July futures as traders try to avoid getting caught with open positions. The nearby WTI contract may stop being a useful reference price at all. And only time will tell whether the fact that the Cushing storage facilities are full is new information to the oil market in general pushing down Brent and other prices.

There is another lesson to be learnt from this experience, namely about the design of futures markets. It seems likely that the delivery conditions for WTI futures will come under scrutiny, and perhaps they can be made more flexible. A more extreme solution is to introduce “cash settlement,” but that is a discussion for another day.

Leave a Reply