Financial markets are in turmoil with the spread of COVID-19 and its consequences for the global economy. Emerging markets suffer particularly acutely in times of financial uncertainty, as global investment portfolios shift to safer asset classes. This means that the COVID-19 shock is creating a “sudden stop” in capital flows for emerging markets. The costs of sudden stops for Latin American and the Caribbean have been significant in previous episodes, and this time we need to understand potential consequences and act with coordinated policy interventions. With these considerations in mind, this post discusses what to expect when you are expecting a sudden stop and how this economic crisis differs from other sudden stops of the past.

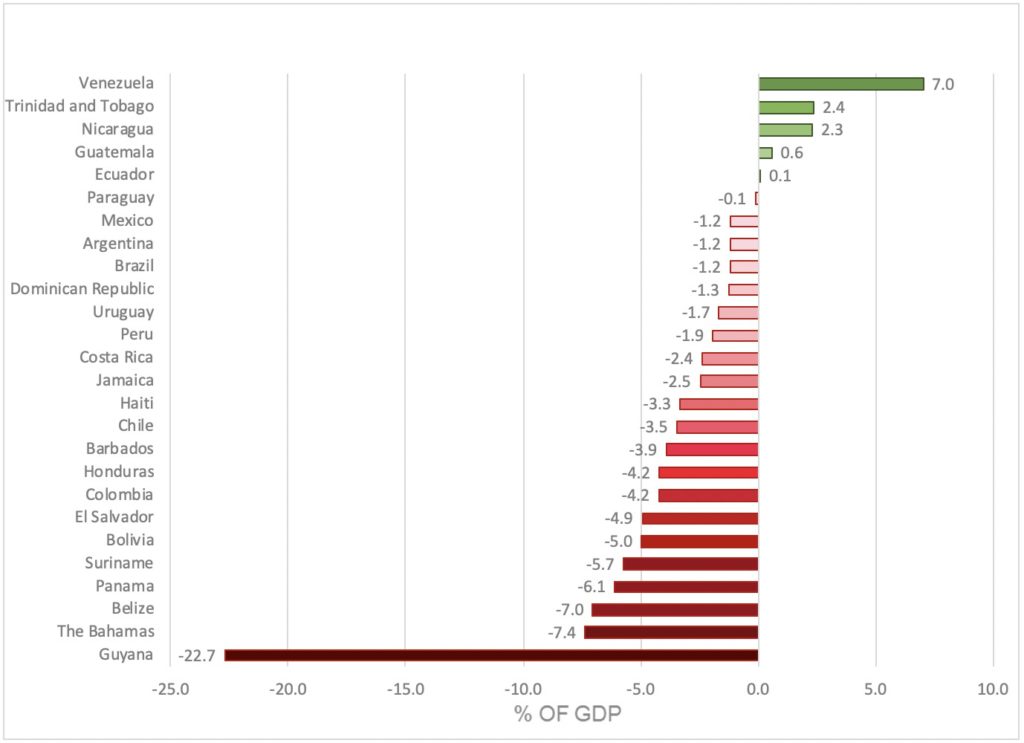

But a definition is first in order. A sudden stop occurs when foreign financing available to borrower countries unexpectedly dries up, forcing an abrupt current account reversal from deficit to surplus, or at least to balance. By year-end 2019, 21 out of the 26 IDB borrower member countries were running current account deficits, some of them substantial. A sudden stop in the financing of those deficits will render them unsustainable.

Current Account Balance (% of GDP, year-end 2019)

But how do countries address an abrupt reversal in outstanding current account deficits? In the standard textbook case, countries may “export their way out” of a sudden stop. In other words, the (real) exchange rate depreciates. Thus, exports become more competitive (and increase), while imports become more expensive (and decrease). The current account then adjusts as needed, and the problem is solved. Or is it?

A Sudden Stop Unlike Others

There are at least two assumptions of the textbook case that fail in the current situation. First, this crisis—unlike past sudden stops—affects global supply and demand. All countries are hit at practically the same time. Who, then, will buy our region’s exports? Real exchange rates will need to depreciate greatly, and even such depreciation may fail to stimulate demand among potential importers with plenty of problems of their own.

Second, real exchange rate depreciations are highly disruptive in the short run for many reasons. The most important involves what are often referred to as “balance sheet effects.” In emerging markets, and certainly in Latin America and the Caribbean, a large portion of countries’ debts are denominated in foreign currency, often US dollars. This means that the balance sheets of indebted agents in those economies are hit in proportion to the real depreciation, increasing their debt burden which is going up exactly when their ability to pay is declining. The result is a vicious cycle that leads to ever increasing borrowing costs (also known as country risk, as reflected in Emerging Market Bond Index—EMBI—spreads). Moreover, experience with previous episodes (all too abundant in Latin America) shows that large real exchange rate depreciations can lead to major losses in output.

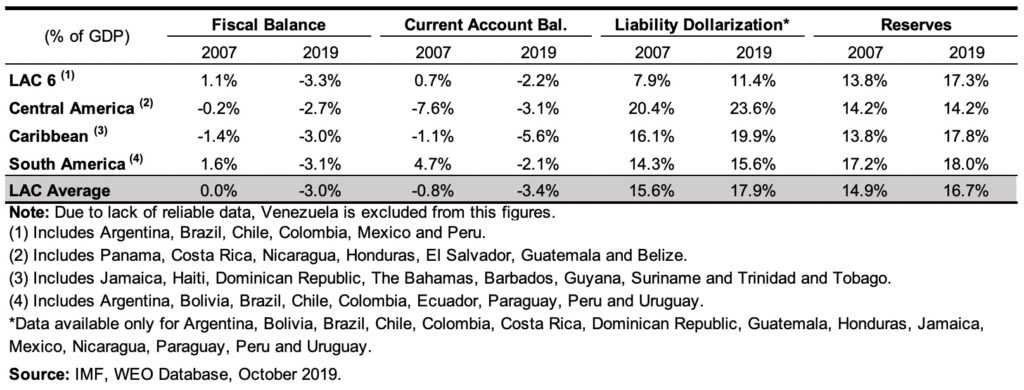

Sudden stops are external in origin: the spark that ignites the fire comes from outside the affected country. Yet a spark cannot become a fire unless there is fuel. The fuel in this instance consists of “initial conditions”: fiscal and external balances, the extent of liability dollarization, and the availability (or unavailability) of reserves in the affected economies that make some countries more or less vulnerable than others.

Weak Macroeconomic Conditions in Latin America and the Caribbean

Latin America and the Caribbean currently displays weak—and combustible—initial conditions. These conditions are notably weaker than in 2008 at the outset of the Global Financial Crisis because fiscal and external deficits, as well as levels of liability dollarization, are on average higher than in 2008. International reserves are also higher—a positive development—but IDB calculations suggest that they are not enough to offset the increased risk from deterioration in other fundamentals.

Factors Affecting Vulnerability to External Shocks

But initial conditions are not destiny. The region’s unfortunately extensive experience has provided important lessons on policy responses to sudden stops in capital flows. In past episodes, countries that were willing and able to loosen monetary and fiscal policy during sudden stops fared better than those that were not. This does not, however, mean that countries that followed tighter policies would have done better had they followed a looser path. It means that having the flexibility to loosen macroeconomic policies during an external financial crisis may be beneficial.

But flexibility in fiscal, monetary or exchange rate policy must not be exercised for just any reason, and stringent preconditions need to be met before flexibility represents a viable option. For fiscal policy, this means sound inter-temporal fiscal behavior and low debt levels. For monetary policy, high levels of credibility are needed to keep inflation expectations low in the face of an expansionary move. In regard to exchange rate policy, flexibility depends on low levels of liability dollarization that reduce the fear of floating. If those preconditions are not met, then policy options in the face of a sudden stop are limited. Countries in that situation would be better advised to seek support from IMF or other official lenders.

This time, unlike any preceding sudden stop episodes, we are all in the same global boat. There is not going to be an easy way to “export our way out” of this crisis because we cannot collectively trade with Mars. We need coordinated policy action, and coordination is now more important than ever. One individual country may not have the fiscal or monetary space to boost the domestic economy and to compensate for the fall in external demand, but if policy interventions are coordinated, the collective boost can support economies’ recovery from this massive sudden stop. This is not a time for economic isolationism. We instead need more integration, not less, to repair the economic damage that will be inflicted by the spread of COVID-19.

Leave a Reply