Emma Näslund-Hadley, IDB Lead Education Specialist

Juan Manuel Hernandez-Agramonte, Deputy Regional Director of Innovations for Poverty Action for Latin America and the Caribbean

Kelly Montaño, Research Associate of Innovations for Poverty Action for Latin America and the Caribbean

“You need imagination in order to imagine a future that doesn’t exist,” advices us Azar Nafisi, author and English literature professor. The quote is more than pretty words. Although Nafisi refers to the role of literature in our lives, she also summarizes in one compelling sentence an entire line of research about our mindsets.

A person’s mindset is defined by individual beliefs about qualities such as intelligence, personality, creativity, and talents, how these qualities contribute to a person’s perspective on the world and how he or she acts in different situations. A person’s mindset influences his or her motivation to do things, and how he or she faces setbacks and failures. While people with a growth mindset can imagine themselves succeeding. They tend to attribute their mistakes to a lack of effort, and seek to learn from these situations, people with fixed mindsets cannot even imagine themselves succeeding with certain endeavors and tend to attribute their failures to a lack of skills (Schoder et al., 2017).

Examples of positive qualities linked to growth mindset include conflict resolution and propensity for problem solving when faced with a challenge; and greater self-regulation and social adaptability. Life outcomes linked to growth mindset compared with fixed mindset include higher levels of resilience (Kammrath & Dweck, 2012), higher academic performance (Blackwell, Trzesniewski & Dweck, 2007; Hanson, Bangert & Ruff, 2016), greater self-esteem and mental health, and lower levels of risky behaviors and criminality.

Growth mindset research is largely confined to industrialized countries. Yet, given the importance of mindset beliefs for life outcomes, it makes intuitive sense to tap into the power of mindsets to seek to influence them in developing country contexts as well. This is what inspired a partnership – of the Ministry of Education of El Salvador, Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) and the Interamerican Development Bank (IDB) – around a study on mindsets of young children and their caregivers. The experimental evaluation seeks to address a gap in the literature as research has yet to investigate if it is possible to promote the development of growth mindsets in children by influencing parental mindset beliefs.

In this blog, we highlight a few insights from the baseline survey of close to 1,800 vulnerable households with young children.

- Caregivers to tend perceive children’s intelligence and personalities as being static

In response to questions about children’s intelligence and personalities, we find that caregivers in our sample tend to see these as static. Since parental mindsets have profound implications for child development (Rowe & Leech 2018; Andersen & Nielsen 2016), it is extremely concerning that these vulnerable children often grow up with caregivers who see these qualities as set in stone. It puts them at an enormous disadvantage compared with peers who are raised by parents who transmit a mindset that intelligence and personality are qualities that you cultivate.

2. Caregiver’s growth mindsets influence parenting behavior, which in turn, have important impacts on children development outcomes.

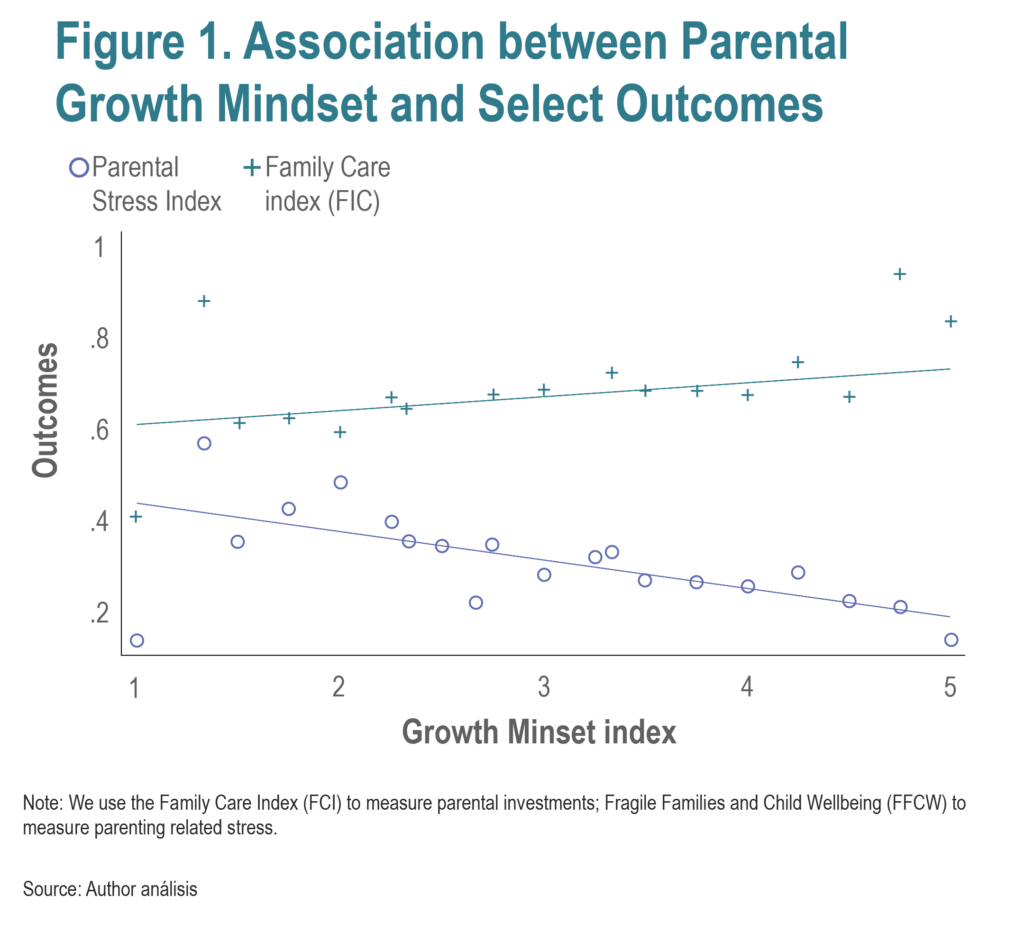

In our data, we find two channels through which caregiver´s growth mindsets promote child development (Figure 1). First, we find that the parental views about intelligence and personalities are compounded by a lower investment in their children. Controlling for socioeconomic status, caregivers’ mindsets are linked to the level of investment they make in their children, including time invested (e.g., playing, reading, and singing) and types and quantities of toys. Second, we also confirm findings from previous research in the United States, which showed the power of mindset over our stress levels (Seek, Ui & Lyoung, 2016). Specifically, we find that stressed parents have a more fixed mindset than other parents, controlling for other factors.

3. Investment in children and stress levels of parents affect children’s development outcomes.

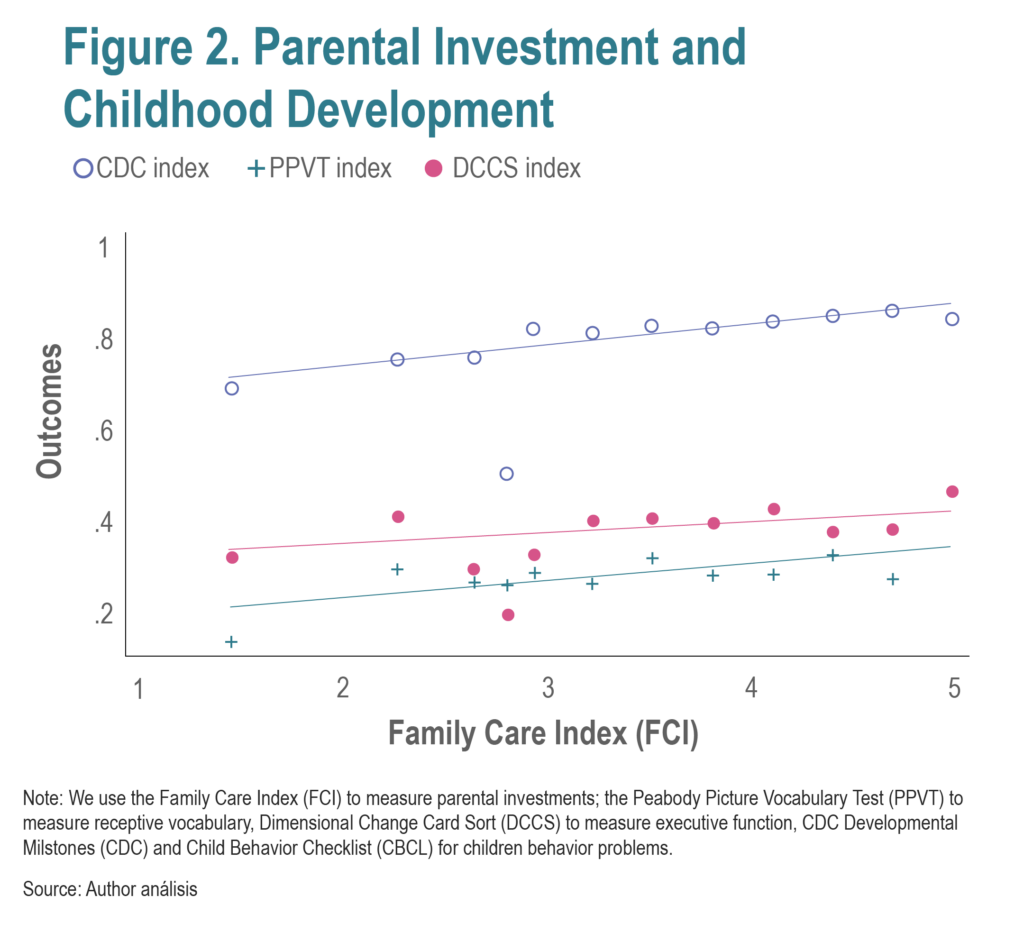

We find that both channels are strongly associated with several child development outcomes. In the case of parental investments, parental investment is associated with a greater vocabulary, executive function, child behavior problems and development milestones (Figure 2).

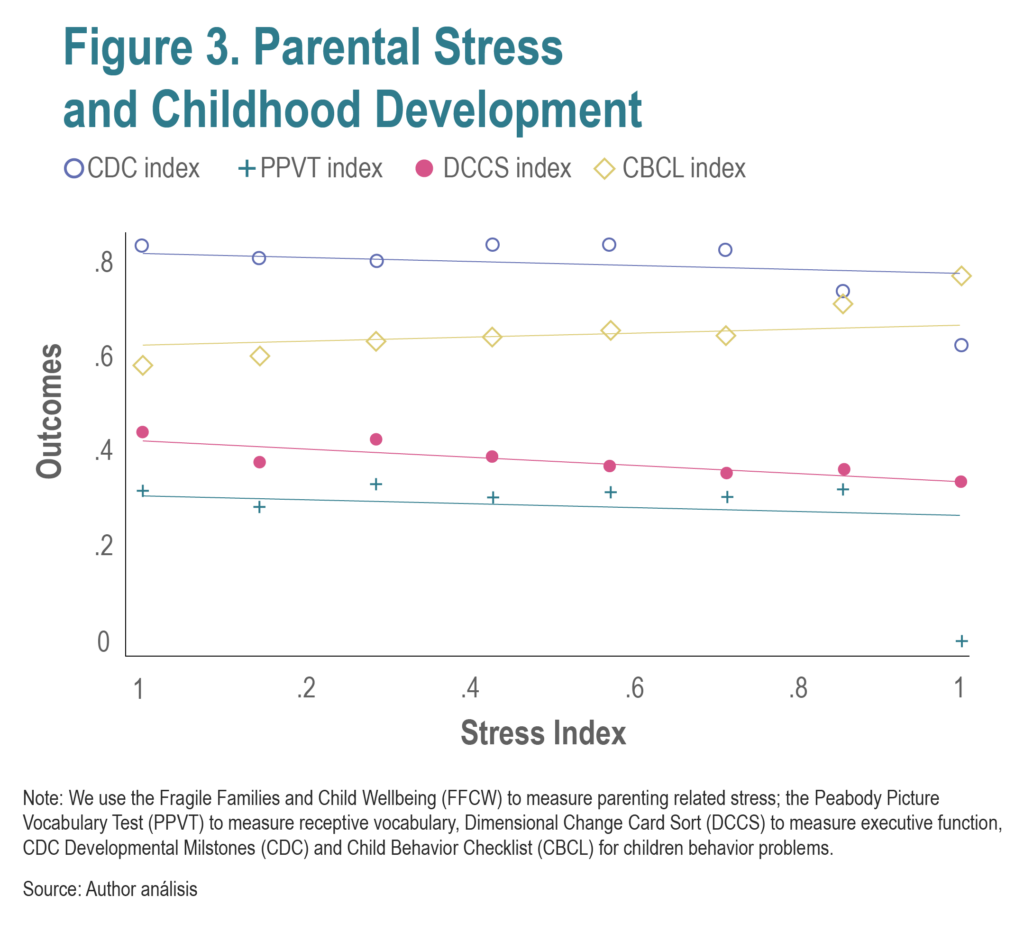

In the case of parental stress, it is associated with higher executive function skills and lower behavior problems of children (Figure 3).

Stay tuned to find out if it is possible to improve child outcomes and behaviors and foster a growth mindset among young children by informing their parents that intelligence, creativity and personality are not static, but malleable. Share your comments with us in the section below, or comment on Twitter @BIDEducacion #EnfoqueEducacion #Hubdedesarrolloinfantil @Poverty_Action

Leave a Reply