In this 21st century, when social change is occurring at a dizzying pace, societies are demanding that people develop an increasing number of the skills needed to navigate complex life challenges. These skills include resilience, critical thinking, and empathy, among others. What are the life skills that matter and how can education systems contribute to people’s prosperity?

Since their inception, educational systems in the Western Hemisphere have been dedicated to promoting both the academic and personal development of students. The first universities were founded in Mexico and the Dominican Republic within a generation of Columbus’ first voyage. These were religious institutions interested in both moral and intellectual growth. Perhaps the first legislation in the Americas to establish a public school system was the marvelously nicknamed Old Deluder Satan Law. Based on the belief that reading the Bible was the best inoculation against the influence of that old deluder, Satan, the Puritans of Massachusetts voted to build public schools to spread literacy. Almost from the beginning of the public education movement in the 19th century, educators were discussing the importance of developing students not only as thinkers, but also as individuals and as citizens.

The development of students as people is if anything more important now than ever. The pace of social change is increasing rapidly, and with it comes increased demands for life skills such as resilience, critical thinking, and empathy. This is education that, if provided effectively, can contribute to success as an individual and as a member of society for an entire lifetime.

Schools and other learning and training settings that cater to youth can play an essential role in offering education in life skills and character. However, for these education programs, a broad array of potential target skills exists (perhaps too many), suggesting the need for guidance on which skills are most likely to make an impact with demonstrable and valuable results.

What are the most useful life skills that education systems can nurture and develop? We attempted to identify life skills that are measurable, malleable, and meaningful, by integrating a broad literature addressing the universe of targets for skills development programs for youth.

Life Skills that Matter

A skill can be defined as anything a person does well. Skills have to do with the degree to which a person effectively engages in behaviors and practices associated with achieving a certain set of goals. Life skills, sometimes referred to as soft skills or deeper learning, are skills that have broad implications for the individual, in that they contribute to the individual’s overall social, emotional, productive, and/or intellectual functioning.

These skills contribute to the success of individuals as members of a social community, by contributing to well-being, the effective use of information, and goal pursuit. They represent general approaches for dealing with conflict, stress, and/or life obstacles. They also tend to contribute to the common good, by enhancing social cohesion, group productivity, and/or effective information processing. Accordingly, social groups tend to value and admire evidence of these skills in members of the community.

A Strategy for Identifying Life Skills that Matter

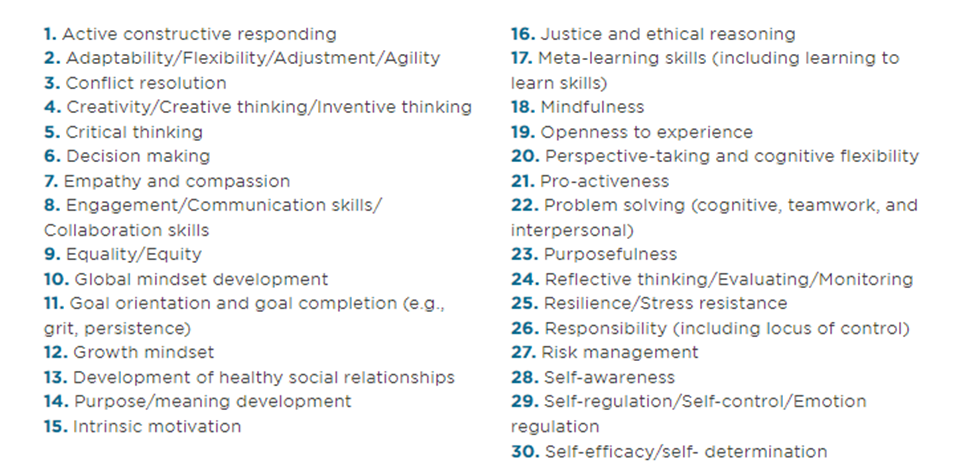

Our report, “Skills for Life: A review of life skills and their measurability, malleability, and meaningfulness,” is meant to aid in the creation of effective programs for skills development. We began by collecting lists of possible targets for non-academic skills development in students and winnowed it down to a list of 30 candidates we thought deserved further inspection.

The “3Ms” in Evaluating Skills

Any of these 30 skills would be a reasonable focus for an educational program, but it is still a bewildering set of options. To narrow the focus further, we reviewed the research evidence for each of these 30 candidates on three dimensions:

- Measurability: Were there validated measures for the skill available now? We were particularly interested in measures that had already been found appropriate for youth, and across speakers of multiple languages of the Western Hemisphere (e.g., Spanish and English).

- Malleability: Was there evidence for how the skill can be shaped? We were particularly interested in skills where a body of research evidence already existed showing that the skill was responsive to formal interventions such as school-based programs.

- Meaningfulness: Was there evidence that those demonstrating more of the skill had better outcomes in life? We were particularly interested in evidence that participation in formal interventions had resulted not only in growth of the skill but also better outcomes of consequence in life such as well-being or effective navigation of social situations.

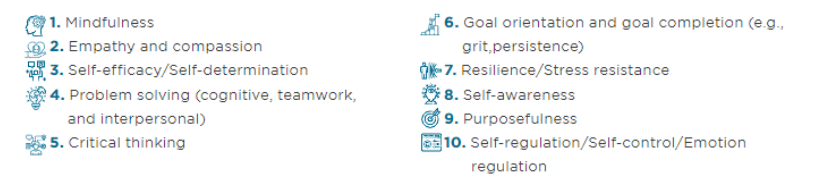

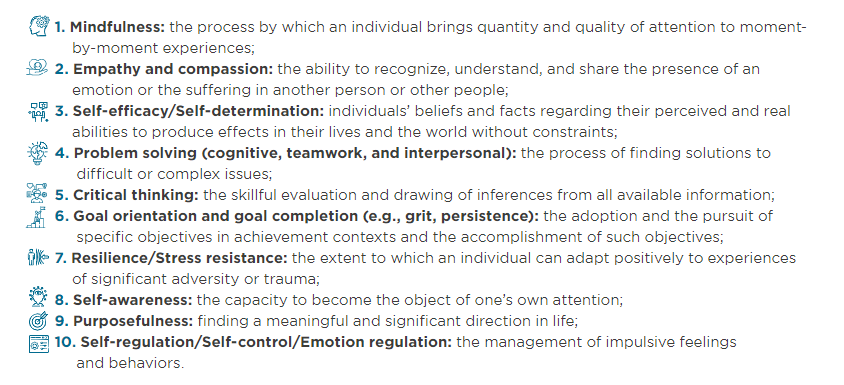

We developed a rating system for each of the three dimensions, allowing us to generate an overall score for each skill. Our conclusions could only be as good as the existing evidence base, but with this caveat in mind we identified 10 skills that stood out from the rest in terms of the combination of measurability, malleability, and meaningfulness. These are the skills for which we found the best evidence that a change in the skill is measurable, possible, and important. In order of overall score, these were:

The report finishes with a set of best practices we gathered in program design, implementation, evaluation, and sustainability. These are intended to help program developers avoid some of the common errors made in program design. We hope the tools we have provided spur new enthusiasm and efforts for building educational skills development programs that will help prepare all our students for life in the 21st century.

The evidence we have presented so far has focused on the best targets for skills development in youth, at least as suggested by the presently available research, based on three criteria of adequate measurement tools (measurability), the potential for effective intervention (malleability), and reason to suspect the training will have consequential desirable life outcomes (meaningfulness).

From our initial list of 30 skills, we identified 10 key skills with the highest levels of measurability, malleability, and meaningfulness (listed below in order from the highest to lowest empirical evidence for measurability, malleability, and meaningfulness):

Finally, we note that the development of life skills can have intrinsic value to youth. Skills such as resilience, problem solving, or the capacity to build positive relationships have tremendous potential for enhancing self-image and quality of life in general, in addition to the more specific consequential outcomes noted already.

To help people better navigate their lives, we need to realize the full potential of education for building life skills that matter as well as academic effectiveness. We believe education systems that build both life skills that matter and academic skills hand-in-hand are feasible and desirable. This combination can sow the seeds for sustainably enhancing the human condition.

For more information, check the IDB latest publication “A review of life skills and their measurability, malleability, and meaningfulness” and stay tuned and follow our blog series on education, economic opportunities, and #skills21.

Hello, I wish a perfect and pleasant day to everyone,

I like life skills articles.

I want to share life skills other than those mentioned in this thread, however, they are beneficial and I recommend reading and investing your time in them.

In summary, these skills are in the form of articles, the first one is:

Focus – It’s meaning and importance, causes of distraction and their treatment, and exercises to increase focus.

The second one is:

Self-Motivation – Definition and Practical Application.

The links for these articles are below:

https://awesomelifetopics.blogspot.com/2023/09/focus%20.html

and

https://awesomelifetopics.blogspot.com/2023/09/self-motivation.html

Hand in hand for a successful pretty life.

Best wishes and regards.