Este artículo está también disponible en / This post is also available in: Spanish

One in five urban households in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) lives in an informal settlement, and two-thirds of people migrating to LAC urban areas settle in these neighborhoods (Inter-American Development Bank, 2021). These residents often have low and unstable incomes, with households led by women, Indigenous people, Afro-descendants, and people with disabilities being overrepresented (Inter-American Development Bank, 2021).

The inadequate infrastructure of informal neighborhoods amplifies the negative impacts of natural disasters and environmental pollution. Overcrowded, unstable dwellings and limited access to basic services such as water, sewage, and electricity increase residents’ exposure to the direct and indirect impacts of natural hazards, including waterborne diseases (Kim et al., 2022). Additionally, the excessive heat associated with climate change can exacerbate the harmful effects of pollution on residents (Satterthwaite et al., 2022).

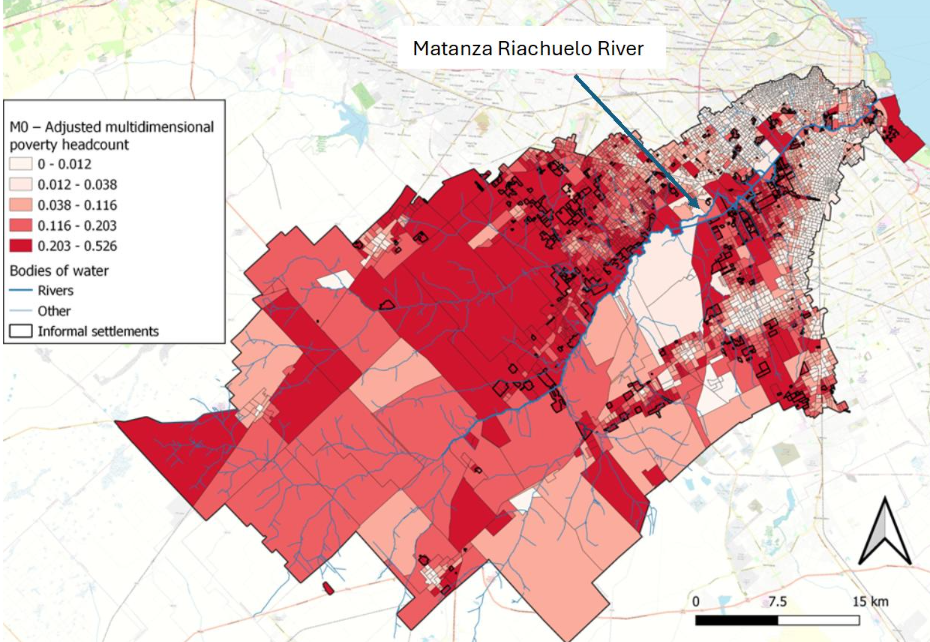

Living in informal neighborhoods makes residents highly vulnerable to the impacts of both natural disasters and environmental pollution. For example, heavy summer rains often lead to sewage overflows and water running into homes (Libertun et al., 2021). These neighborhoods are typically built in at-risk areas prone to landslides, including large-slope terrains, hilltops, or river floodplains. Between 2004 and 2013, 611 landslides were recorded, causing 11,631 deaths in 25 LAC countries. Fatalities were significantly higher in informal neighborhoods, with 81 percent of the fatalities occurring in these areas despite only 41 percent of the fatal landslide events happening there (Sepúlveda and Petley, 2015). In São Paulo, Brazil, a 2016 study found that 48 percent of landslides occurred within 100 meters of informal settlements, and 82 percent within 300 meters (Perez and Martins, 2016).Figure: Spatial distribution of multidimensional poverty in the Matanza-Riachuelo River basin, Argentina.

The vulnerabilities of informal settlements to natural disasters are further exacerbated by their exposure to environmental pollution. An article in Oxford Development Studies by Ann Mitchell and Mariano Rabassa of the Universidad Católica Argentina, titled “Inequality in environmental risk exposure and procedural justice in the Matanza-Riachuelo River Basin,” examines this issue by analyzing one of the most industrialized and contaminated river basins in Argentina and one of the most polluted worldwide (Blacksmith Institute & Green Cross Switzerland, 2013). The Matanza-Riachuelo River Basin (MRB), home to 4.7 million people (10 percent of Argentina’s population), has been the focus of an environmental remediation plan introduced in 2010 (ACUMAR, 2010).

Environmental justice literature suggests that the goals of social equity and environmental care are interconnected. This connection depends on which socioeconomic sectors are initially more exposed to environmental burdens (Mohai et al., 2009) and on procedural justice, meaning the extent to which different groups can participate in decision-making processes that determine the distribution of these burdens (Banzhaf et al., 2019). These insights shaped the dual focus of the article.

The paper uses census tract-level data and a spatial regression model to analyze the correlation between multidimensional poverty and three types of environmental risk: environmental incidence of productive establishments, open-air waste dumps, and proximity to surface water contamination. The authors constructed the multidimensional poverty measure using the Alkire and Foster (2011) method and household-level census data (INDEC, 2010). Environmental risk from productive establishments is proxied by the Environmental Incidence Level, an indicator calculated by the regulatory authority based on the establishments’ legal declarations (ACUMAR, 2018). The study finds that lower multidimensional poverty areas face greater exposure to the incidence of productive establishments—contrary to the generalized perception in the MRB case and environmental justice research from high-income countries (Mohai et al., 2009).

However, this finding aligns with research from other Latin American countries (see Grineski & Collins, 2010; Lara-Valencia et al., 2009; and Habermann et al., 2014). This pattern seems to be because in Latin America, more affluent households and businesses tend to locate in city centers with better urban and transport infrastructure, while disadvantaged households occupy less developed peripheral areas. In contrast, the study finds a positive and statistically significant correlation between multidimensional poverty and exposure to open-air waste dumps, suggesting that waste dump clean-up produces positive synergies between social equity and environmental restoration. Furthermore, the success of environmental remediation plans depends on effectively integrating local residents into the process.

To sum up, we invite you to continue exploring how the IDB promotes improved and sustainable neighborhoods with these publications. In Bairro Ten Years Later, the evolution of community projects over a decade is analyzed, highlighting the changes and improvements achieved. The publication Impact of Self-Construction Housing Improvement Programs: Evidence for Neighborhoods presents concrete evidence on the benefits of self-construction in the quality of life of residents. Additionally, Do Slum Upgrading Programs Impact School Attendance? examines how neighborhood improvement programs can influence school attendance, emphasizing the importance of a safe and dignified environment for educational development. Explore these resources to better understand the IDB’s efforts in creating more sustainable and resilient communities.

Leave a Reply