Este artículo está también disponible en / This post is also available in: Spanish

For decades, the eradication of poverty has been the goal of Latin American and Caribbean countries. Even so, 32.1% of the population has an income below the poverty line and 13.1% below the indigence line. Measuring poverty is vital to eradicate it. Therefore, it is relevant to ask why the most widely disseminated data on poverty are based on income level despite the fact that poverty is recognized as a multidimensional concept. Poverty goes beyond the lack of income, as a person can suffer multiple disadvantages at the same time: poor health, malnutrition, lack of water and sanitation, electricity, precarious work, etc.

In this article we present the results of a recent study that proposes strategies to measure poverty in segregated cities in a multidimensional way. We will explain how the Housing and Urban Development Division of the IDB is working to reduce poverty and social exclusion in the cities of our region. Don’t miss it!

Let’s get to know the different types of poverty

Spatially segregated cities (those where vulnerable and affluent neighborhoods are physically separated) pose a challenge in terms of poverty measurement. Residents of informal settlements experience various deprivations directly associated with informality, among others:

- Low quality public services

- Inadequate policies (these are high crime areas),

- Lack of a legal address (necessary to access jobs or financial services),

- Threat of eviction

All of these aspects are not adequately captured by traditional income-based poverty measures. Also, since poverty is defined in relation to social standards, in cities with high levels of inequality it can be difficult to define deprivation thresholds to identify the poor.

People are multidimensionally poor when they accumulate deprivations.

A research recently published in Development and Society shows how Sen’s capabilities approach and Alkire and Foster’s multidimensional poverty measurement method deepen the understanding of the scale, characteristics and spatial distribution of poverty in segregated cities. The conclusion is that capabilities provide a more appropriate metric than income for computing poverty because the abilities to convert resources into welfare opportunities (capabilities) and achievements (functionings) vary according to individual, social, environmental and institutional factors (conversion factors).

For example, the resources needed to enable a child to attend school are greater if he or she has a motor disability. Likewise, school attendance may be influenced by proximity to schools or public transportation, as well as neighborhood insecurity. A direct approach to poverty measurement based on capabilities and functionings avoids the problem of inadequate measurement of deprivation when there are territorial price disparities, or when some needs are met through goods and services provided by the state or civil society, rather than through market transactions. Alkire and Foster’s method identifies people as multidimensionally poor when they experience an accumulation of deprivations (in selected dimensions and indicators) that exceeds a certain threshold.

A multidimensional poverty index

Using the city of Buenos Aires as an example, the study used data from the Annual Household Survey to construct a multidimensional poverty index in the dimensions of health, habitat, education and work. The results show that, as expected, informal neighborhoods have a higher incidence of multidimensional poverty and a greater intensity of deprivation among the poor. They also show how the gaps with respect to formal neighborhoods are more pronounced than when comparing deprivation indicators separately. These results show the relevance of using multidimensional poverty measures over other methods such as the indicator dashboard to achieve a better measure of how the simultaneous occurrence of deprivation (called “clustering of disadvantage”) is distributed within the city.

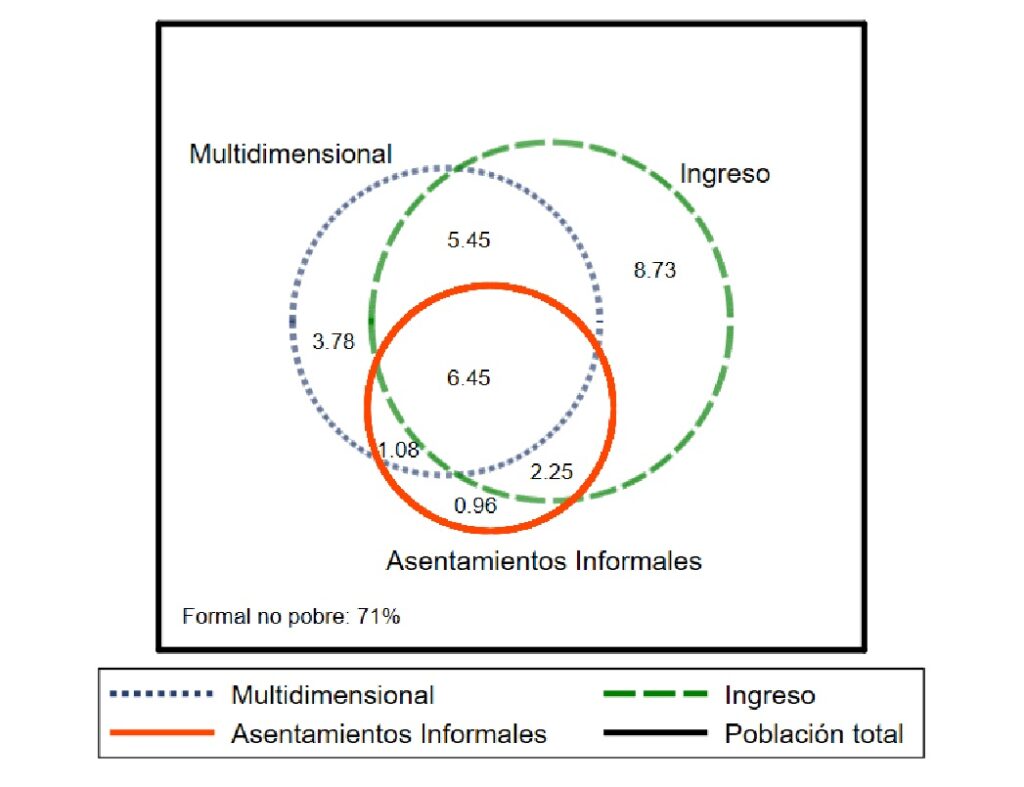

Comparison of income vs. multidimensional poverty:

The comparison between the results of the multidimensional poverty study with income poverty shows a positive association between the two measures. However, the correlation is weaker and there is less overlap in terms of who is identified as poor in informal settlements than in the rest of the city. The income poverty measure produces a greater underestimation of deprivation in informal settlements than in formal neighborhoods (10% of people are multidimensionally poor “invisibilized” by the method). After adjusting for the underrepresentation of the population in urban settlements in the official household survey, these territories account for only 10% of the city’s population, but close to 50% of the multidimensionally poor.

The Alkire-Foster measures can be disaggregated by dimensions and population subgroups, which facilitates the understanding of the heterogeneity of urban poverty. While work and health, both strongly associated with income poverty, are the most frequently deprived dimensions in the formal city, housing and health are more frequent among the slum poor.

Moving to Action: Implications for Public Policy

The choice of methodology for poverty measurement and the way in which the measure is constructed have important implications in terms of public policy. The use of a multidimensional poverty measure in an urban setting, together with the appropriate choice of its component dimensions and indicators, helps to identify certain types of deprivation with low prevalence for a city in general, but high prevalence in specific areas. In the aforementioned study, this methodology makes it possible to show that informal neighborhoods show high dropout and over-age schooling rates, unlike the rest of the city.

In general, the use of multidimensional poverty indices in segregated cities highlights the need to focus poverty reduction policies on informal settlements. It also shows that integrated, community-level anti-poverty programs that provide multidimensional social assistance to the most critically deprived households must be provided. For this reason, we in the Housing and Urban Development Division of the IDB work to overcome poverty and structural social exclusion in LAC cities through neighborhood upgrading policies and programs aimed at improving living conditions in informal neighborhoods. These programs focus on the provision of urban services in a comprehensive manner to increase the well-being of low-income communities. These programs generate benefits in the short and long term, especially when complemented with other programs that address issues such as public safety or environmental resilience.

If you want to learn more about the IDB’s work improving neighborhoods, we recommend you read the following articles:

Leave a Reply