by Guest blogger, Hilaire Notewo-Petsoh

When you have friends, and you travel all the time, the least you can do for them, beyond photographs and Facebook status updates, is bring back some tangible souvenirs from your trip. Lately, I have been traveling a lot to Haiti; and every time I land in that beautiful country, I always like to shop. The diversity and the beauty of the artistry displayed along the streets and other commercial avenues is compelling. Even though I don’t go to local markets, mostly because policies at work discourage it, I always try to find a way to interact with local business owners; I enjoy engaging with small business retailers, to learn more about how they do business, and sometimes to test their negotiations skills.

One thing I find fascinating in Haiti is the pride these business owners have when selling their products. My guess is that this pride is the result of the passion and effort they put into the service they render, and the hard work they put into crafting their wares. I usually buy original, creative, local handmade objects. Unlike in the countries the north where prices are usually posted and fixed, in Haiti, as in many southern countries, a commercial interaction is always an exercise in negotiation. There is always a preamble where the buyer asks the price of a particular item, and the seller replies. This is followed by the back and forth in which both parties make offers and counteroffers until they get to a mutually satisfying benchmark or seller and buyer come to realize they can’t agree on a price. More often than not, motivated buyers and sellers reach an agreement.

Though I’ve observed this process in a number of countries, I am struck by how, in Haiti, these negotiations have often left me feeling confused. The official currency used in that country is the Haitian Gourdes. However, vendors always price items in dollars. But although, often, items on shelves display price tags with the widely recognized dollar (“$”) sign, if you don’t pay close attention you might think the price displayed is in US dollars.

For example, when we went to visit the famous “Sans-soucis,” a very beautiful and touristic place in the northern part of Haiti, where King Christophe erected his palace, I couldn’t resist the urge to buy beautiful handmade post cards a young man was selling. When I asked him the price, he said they cost ten dollars each, but offered no additional information. I went to pay him in Uncle’s Sam currency, after negotiating the price down to seven dollars each, a process further complicated by the fact that I was calculating the price in terms of exchange rates for Central African CFA Francs, the currency used in Cameroon. Though we had reached a price, I found it odd that these post cards were so expensive and asked why they were so costly. The vendor explained that the “Haitian dollar” wasn’t that “strong.”

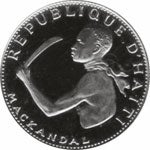

Imagine my surprise to learn that in addition to the Gourde, Haiti had its own dollar. In all the literature I reviewed when planning my trip there was no mention of a Haitian dollar; consistently, the materials indicated Haiti’s currency was the Haitian Gourde. At that point, I became more curious and made inquiries of the Haiti country office staff. I was hoping someone could should me a Haitian dollar coin or note. That’s when I learned that no such note exists – the staff residing in Haiti explained that there was no such thing as a Haitian dollar. They further explained that many Haitians use the expression dollar rather than to name prices in Haitian Gourdes. One member of the staff elaborated further, “one Haitian dollar is equal to five Haitian Gourdes.” He even showed me a coin which has “cinq gourdes” embossed on it. He said that the coin was the embodiment of the famous, mythical Haitian dollar.

After a little more research, I learned that the term “Haitian dollar” is a throw back to when the United States dollar was equivalent to 5 Gourdes, or a single “cinq gourdes” coin. It is a numeric device, not an actual currency. So the price of my 7 dollar post card was actually thirty five Gourdes. At today’s exchange rates, which fluctuates between forty-five and forty-six gourdes for each US dollar, the cost per postcard is closer to seventy-five cents in US currency.

Later that same day, when we returned to the hotel, one of my colleagues went to the bar and asked for a beer. The bartender told him that the local beer costs eight dollars. My colleague was stunned and surprised that the local beer was so expensive. When he asked another Haitian coworker why that beer was so expensive, the coworker explained that it considered expensive because eight Haitian dollars was the equivalent of ninety-seven cents, just a little less than a US dollar.

At the end of the day, I came to the conclusion that colloquial reference to the Haitian dollar that produces much confusion. Although the Haitian “cinq gourdes” coin is seldom seen, local vendors frequently quote prices to foreigners in Haitian dollars as if they expect to be paid in the elusive coins.

As a result, my advice to travelers visiting Haiti is to be aware that they are likely to hear prices quoted in dollars, and that it is important that they remain vigilant in clarifying prices with vendors, for in all probability the vendors are making use of this numeric device. Failing to understand this dynamic can be costly. The seller may take advantage of a purchaser when money changes hands if the purchaser seems willing to pay in US dollars. My practice, now, is to ask the Vendor to give me the price of an item either in Haitian gourdes or in US dollars.

Leave a Reply