Higher climate risks, higher financial costs

Climate risks pose physical and transition risks. Nonetheless, the creditworthiness assessment has yet to distinguish climate risk impacts explicitly. In fact, only after the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015 incipient studies towards assessing climate risks have been observed, allowing today’s broad acknowledgment of the significant exposure to such risks. For example, rating agencies such as Fitch and Moody’s are now assessing the implications of those risks within their credit analysis. Their recent reviews indicate that (rated) debt with high or very high environmental risk exceeds US$4 trillion worldwide and will represent average annual financial costs of 3.3% — and up to 28% — of the value of real assets without adaptation measures.

Climate change projections at scale are fundamental

Despite the growing significance of climate exposure in influencing financing conditions, there needs to be more focus on particularly vulnerable countries, such as the Caribbean region, which already faces high levels of debt and limited capacity, given the need for resilient investments. For example, projections from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (CMIP6) highlight the following trends for the Caribbean:

- Continued warming throughout the region, with increases in mean temperatures and the frequency of heat waves, will exacerbate existing challenges such as coral reef bleaching, sea level rise, and extreme weather events, including hurricanes and droughts.

- Shifts in precipitation patterns, with some areas experiencing increased rainfall intensity and others facing more prolonged dry spells, impacting agriculture, water resources, and ecosystems. Nevertheless, using this information at a local scale still requires adequate methodologies and training.

A forward-looking approach for the Caribbean

Therefore, while it is clear the need for climate change strategies tailored to the distinctive perspective of the Caribbean nations, particularly in light of its financial implications, knowledge and data are still scattered and rare for this region. Therefore, as a part of the continued work to fill this knowledge gap, the IDB partnered with Wealth Fair Economic and ClimateUEA to assess the impacts of climate change on the sovereign credit ratings, probability of default and cost of debt for a set of Caribbean countries. The study adopts a forward-looking approach based on climate change projections, finding that sovereign ratings of most countries may face notch-downs and that the probability of default would increase by 10%. Further, in the most stressed case, those downgrades would translate into higher interest payments of around US$1 billion per year for sovereign debt. While these figures directly refer to sovereign debt, it should be noted that the financial burden of greater climate vulnerability will also increase the cost, or even availability, of capital for the private sector.

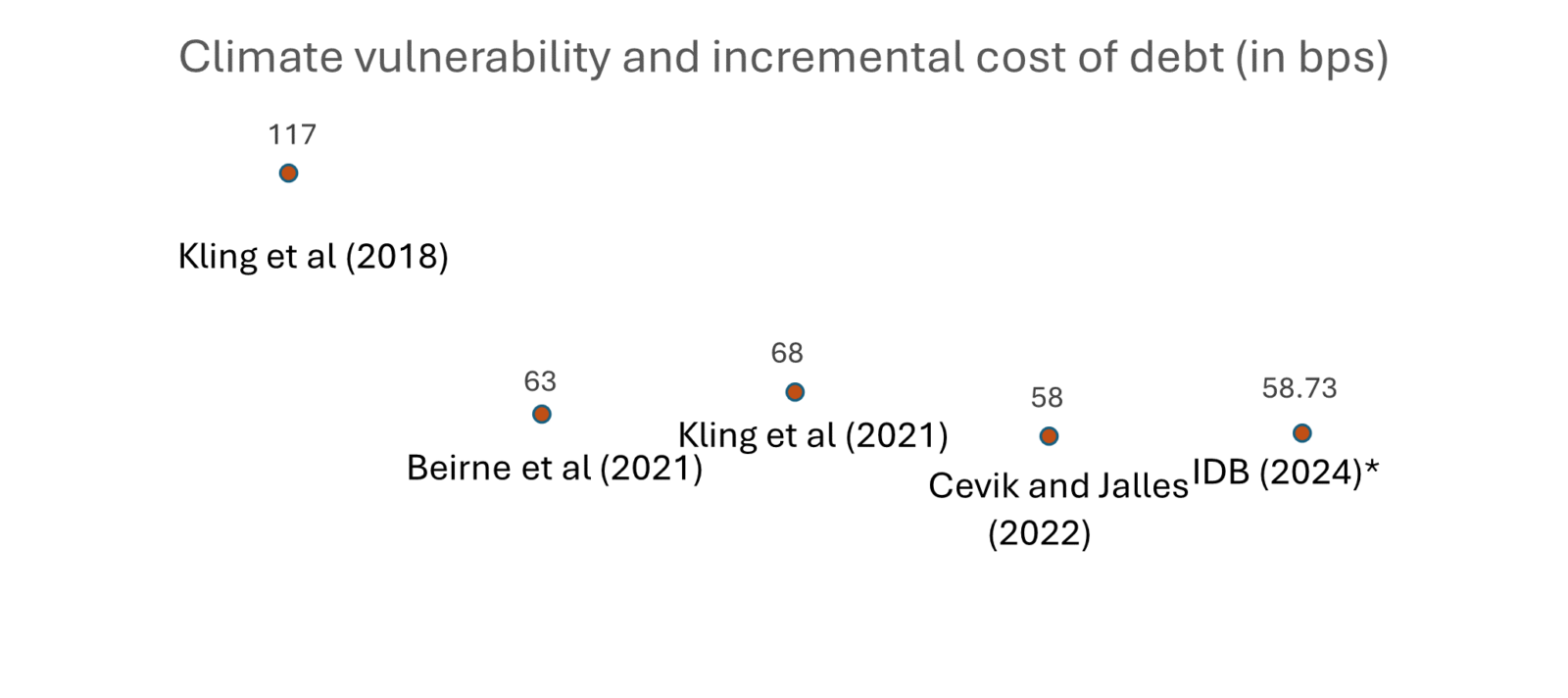

The findings of this recent analysis are consistent with existing literature based on historical data. Although the differences across studies should be carefully accounted for, the available estimates provide an indicative ballpark of the impacts of climate risks on the cost of debt. Figure 1 plots those estimates suggesting a higher cost of debt in the range of 58-117 bps due to increased climate vulnerability. In the case of IDB (2024), in the most stressed case, the median incremental interest rate is 58.7 bps (min=19, max=98). For example, the risk-free, 10-year US treasury yields would imply over 10% higher cost of debt.

Note: The figure presents the median incremental interest rate for IDB (2024). For other studies, it presents the available mean estimate. BPS: Basic points. Kling et al (2018), Beirne et al (2021), Kling et al (2021), Cevik and Jalles (2022), IDB (2024)

What policymakers can do: 4 key recommendations

Previous literature also suggests that investing in adaptation is cost-effective. Nonetheless, they require technical assistance, solid data, and enhanced capacities. In this sense, some policy implications are:

- Data remains a key input that Caribbean countries need to invest heavily in. Statistical infrastructure and data gathering are needed for better economic analysis, including the impacts and opportunities created by a transition to a low-carbon economy, such as enhancing transparency to issue thematic bonds and accessing new innovative financial instruments such as Sustainable Link Loans/Bonds.

- Owning updated climate scenarios downscaled to the region and, if possible, to a country level, while considering the uncertainties, will allow a better assessment of the reality of climate change in the region.

- Innovative finance mechanisms are a new option to enhance the countries’ resilience and mitigation opportunities. Nonetheless, they require long-term strengthening of the capacities in the Ministries of Finance and Environment, which, if not met, could erode incentive compatibility and deter credibility.

- Decarbonization will need to be assessed and evaluated to help create alternative sources of fiscal revenues, as fuel duties and carbon taxes are expected to fall and therefore deteriorate fiscal revenue. This will require the development of adequate just transition strategies.

In a nutshell, climate risks increase financial costs, and they can be very important. There is a strong argument for Caribbean countries to better assess economic costs of climate change, which can also strengthen their standpoint in the international climate stage and debt markets.

Leave a Reply