Increasing COVID-19 vaccine take-up is key to protecting people from death and disability. Research increasingly shows that COVID-19 not only increases the risk of premature death but also can have long-lasting consequences resulting in chronic conditions and incapacitating illnesses –also known as long COVID. However, despite the benefits of vaccines, governments are still struggling to vaccinate large proportions of their population. According to PAHO, 10 out of the 13 countries in the Americas that have not reached WHO’s 2021 goal of 40% vaccination coverage by February 2022 were in the Caribbean, and even fewer countries have achieved WHO’s 2022 goal of vaccinating 70% of the population by mid-2022. Although limited vaccine supply was the main reason for low vaccination rates at the beginning of the pandemic, this is no longer the case in most LAC countries during 2022.

Belize is one of the countries facing these challenges. The country has made significant progress, reaching 50% of the population fully vaccinated by December 2021. However, despite enough supply to cover 100% of the population, the vaccination rate started slowing significantly since generating concerns (Our World Data). The Belizean government has been doing formidable work to increase the impact of their vaccination campaigns. Still, after more than two years of the pandemic, challenges remain to ensure all people get vaccinated, especially those at risk.

The Belizean Ministry of Health and Wellness (MOHW) partnered with the IDB and other organizations to understand the reasons behind vaccine uptake and hesitancy and measure the effectiveness of different interventions to address them.

What are the views of unvaccinated persons about the COVID-19 vaccine?

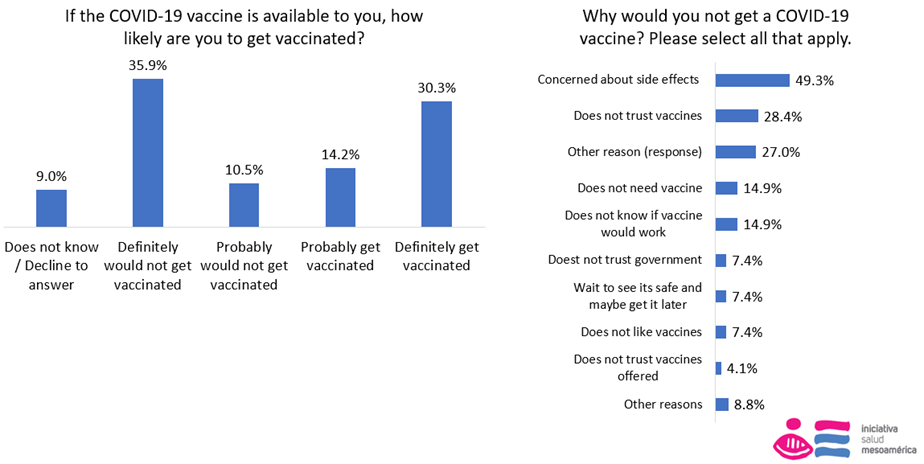

According to a nationally representative household survey conducted by the Salud Mesoamerica Initiative (SMI) in September-October 2021, the perceptions of easy access to vaccines, higher vaccine safety, and increased protection were among the main reasons explaining people getting vaccinated. Among the unvaccinated (20.7% of the sample), 65.4% showed some degree of hesitancy, and intentions to get a vaccine increased if they perceived it would protect their health, it would help them resume social activities, or follow government mandates. On the contrary, fear of side effects, lack of trust, and a perception of not needing a vaccine are among the reasons for not getting vaccinated. These findings are similar to those found in other studies in Caribbean countries.

Figure 1: Vaccination intentions and views among unvaccinated people

Can a positive message increase interest in COVID-19 vaccines?

In Belize, an IDB social protection and health behavioral economics team worked closely with the Ministry of Health and Wellness (MOHW) and a digital marketing firm (IdeaLab Studios Digital Marketing, financed by the IDB) to design and launch behaviorally informed Facebook campaigns. The campaigns were sequentially displayed to the entire population of Belizean Facebook users and informed by previous research, aimed to encourage vaccination take-up by highlighting its safety (“It’s Safe” campaign), effectiveness (“It’s effective”), probability of side effects (“When vaccinated…”), self-protection (“Are you protected?”), and children’s eligibility (“Children”).

Within one of the campaigns, we experimentally tested the effects of different messages on online engagement. Using data for around 260,000 Facebook users (about 65% of the population who were eligible at the time of the study) and making use of the Facebook AB Testing tool, three different messages were randomized among Facebook users in Belize by district: “When vaccinated… (i) only 3 out of 100 reported discomforts“; (ii) “ … few people have discomfort“; and (iii) the majority didn’t have discomfort.” All the messages included the sentence: “Click here (link) to find your nearest vaccination site” at the end, giving them access to a website containing scientific information related to the vaccine’s effectiveness and instructions to get their appointments. We track the number of “clicks” on the ad as a proxy for interest in getting information about COVID-19 vaccines.

We find that the “Majority” sub-campaign (compared to the “3 out of 100” message, which was the base category) was more effective at raising people’s interest, implying that a positive message (communicating no discomfort) seems to work better than a negative one (communicating discomfort).

Figure 1: Facebook AB Testing tool

What else has been done?

Protecting people against the COVID-19 virus has been a priority for the Belizean government. In addition to the digital campaign, the government has been sending vaccination teams to remote villages, hospitals, schools, and elderly centers, and increased their presence on local TV shows and radio advertising specific vaccination sites and events. The government also created a website including scientific information related to the vaccine effectiveness and the mortality and hospitalizations rate of the vaccinated compared to the unvaccinated by age group.

However, a lack of evidence on which communication strategies work and pandemic fatigue could challenge this work. In this study, we contribute to the discussion and hope it could serve as preliminary evidence for public health officials to consider if they wish to tackle vaccine hesitancy.

Leave a Reply