Despite its significant decline in recent decades, poverty remains a persistent and complex development challenge in Latin America and the Caribbean. Understanding how poverty varies in the region is relevant but not simple. In particular, inequalities between men and women can go unnoticed in poverty analysis, as all household members are often considered poor when the household is, ignoring any heterogeneity among its members. Measuring these inequalities presents challenges that must be addressed in the search for ways to design evidence-based public policies that are sensitive to these inequalities.

How do we measure poverty?

Poverty has traditionally been measured using monetary approaches: that is, the monetary poverty rate is the proportion of people whose household income per capita is below a predetermined poverty line, which generally considers what is needed to meet a set of basic needs. These measures are widely used and form the basis of official poverty statistics. A recent example is the report on poverty and equity in Suriname conducted in conjunction with the World Bank.

A complementary measure is multidimensional poverty, which assesses deprivations in various areas of well-being such as health, education, housing, and employment, among others. In this case, the poverty rate corresponds to the proportion of people considered multidimensionally poor. A person with income above the poverty line can be considered poor if they lack access to certain basic services and opportunities. Given the nature of this measurement, there is a range of indices with different weightings and areas of well-being.

In this regard, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) has recently developed a specific index for the region called IPM-AL, which offers a view of regional poverty and considers factors relevant to the region’s structural characteristics.

Challenges in measuring poverty between men and women

One of the main challenges in analyzing differentiated poverty between men and women is that the unit of analysis is households. Most poverty metrics are based on household-level data and are not disaggregated by the roles of each member, their responsibilities, or access to resources. In other words, it is assumed that resources within the household are distributed equitably among all members. This hides existing inequalities within the household and, in particular, can make the specific deprivations faced by women invisible.

Even when individual-level data exists, it often does not capture key dimensions of poverty that disproportionately affect women, for example:

Additionally, the set of female-headed households is often used as a substitute for measuring female poverty, but this approach omits many women living in poverty in male-headed households, which can lead to erroneous diagnoses and public policies.

What does income poverty tell us?

According to the Inter-American Development Bank, more than 200 million people in Latin America and the Caribbean live in poverty, and nearly 100 million in extreme poverty. Women are overrepresented among the extremely poor population, accounting for 53% of this group.

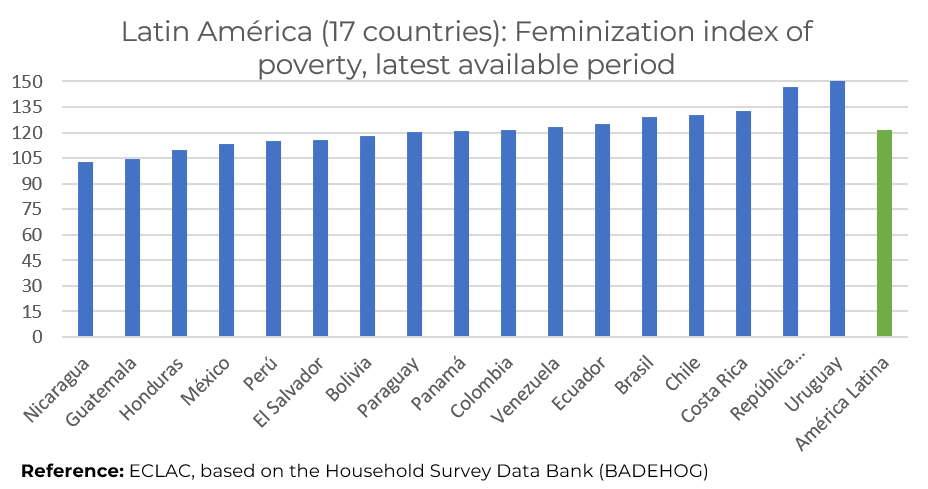

In line with this, ECLAC’s feminization index in poor households, which compares the number of men and women aged 20 to 59 in poverty, shows that in the region, the percentage of women in poverty tends to be higher than that of men of the same age. These gaps in poverty incidence are even greater if only women of childbearing age are considered. Additionally, female-headed households, especially single mothers, are more likely to be poor due to lower labor income, higher care burdens, and structural barriers to economic opportunities.

What does multidimensional poverty reveal?

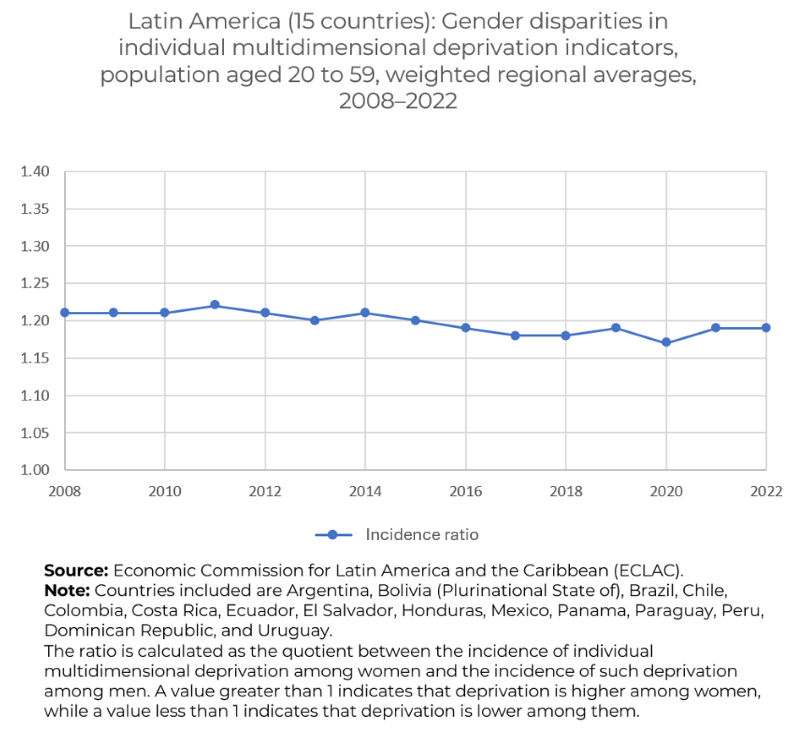

ECLAC’s recent report addresses the issue of using households as the unit of identification and presents multidimensional poverty estimates using a modified strategy. With this, ECLAC data reveals significant gaps in deprivations related to housing quality, educational level, and working conditions between men and women.

Women aged 20 to 59 in our region face higher individual-level multidimensional poverty rates than men in the same age range. This was evident in 2022, when it was 1.19 times higher. Disparities between men and women are particularly marked in non-participation in the labor force due to unpaid domestic care, an indicator in which there was almost no lack for men but ranged between 15% and 20% for women. Additionally, these inequalities intersect with factors such as ethnicity, age, and geographic location. For example, indigenous and Afro-descendant women often face accumulated disadvantages that intensify their poverty situation.

What can we do?

Addressing inequalities between men and women in poverty requires multidimensional and sensitive approaches:

- It is essential to have better data—particularly individual information disaggregated by sex and age.

- Social protection systems must recognize unpaid care work and promote women’s access to quality jobs and childcare services.

- It is crucial to expand access to education, health, and financial services, especially in rural and marginalized areas. Policies should promote formal employment and eliminate structural barriers to female labor participation.

Finally, integrating diagnostics that are sensitive to differences between men and women in national poverty reduction strategies is crucial for designing more effective and comprehensive public policies.

Leave a Reply