Chile and Colombia are two of the most solid economies in Latin America and the Caribbean. While in 2020 they contracted 5.8% and 6.8%, respectively, they were among the strongest performers in the region amid difficult circumstances. Both are open market economies, with flexible exchange rates and access to foreign markets. They also have faced social unrest and protest regarding inequality and other issues in the last couple of years.

Given their similarities, it was striking to discover that in 2020 Colombians increased their savings abroad by 2 percentage points of GDP while Chileans repatriated assets instead of engaging in their usual behavior of saving 2% of GDP abroad each year. Were Chileans more confident about their economy? Were Colombians scared about their country’s prospects?

Effective Management of a Difficult Situation

It turns out that both countries managed the situation well. Government policy in both allowed them to tap unconventional financing sources, which successfully helped to smooth financial net flows in a global environment in which external financing to Latin American and Caribbean countries was severely strained.

In our 2021 Macroeconomic Report (see Chapter 3) we looked at how external sector financial flows behaved in Latin America and the Caribbean in 2020. Particularly, we focused on both asset and liability flows in the financial account. Asset flows show residents’ behavior: Did they save abroad or repatriate their money? Liability flows, by contrast, reveal the behavior of nonresidents: Did they lend or invest more in the country, or did they take their money somewhere else? By adding both asset and liability flows, we obtain the net external financing flow to a country.

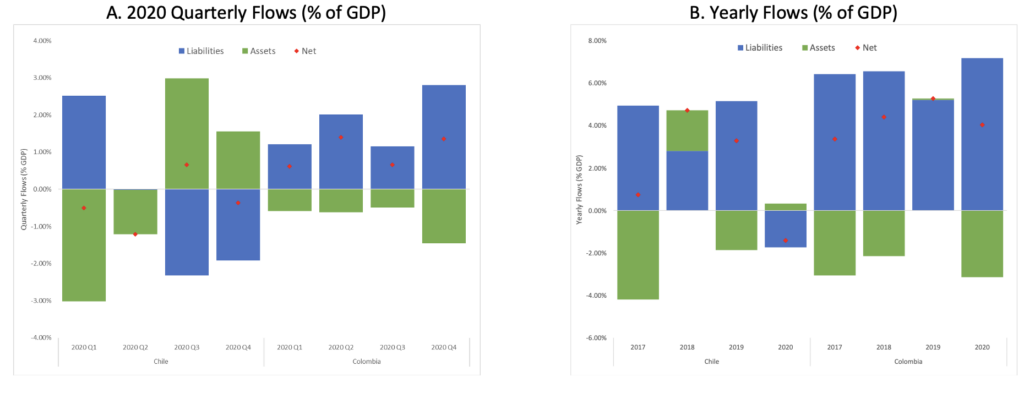

In the past century, foreign investors dominated the scene, particularly in emerging markets like Latin American and the Caribbean. That meant net financing was dominated by liability flows, while asset ones were negligible. But domestic investing has gained more relevance in net capital flows since the 2000s, and is no longer insignificant. Figure 1, Panel A shows Chile’s and Colombia’s quarterly flows in 2020. In these figures a positive value is an inflow of funds to the economy: an increase in external liabilities or a decrease in external assets.

Figure 1. Capital Flows in 2020 for Chile and Colombia

Note: We use the GDP in USD of 2019 for each country.

We can see how asset and liability flows offset each other in both countries during 2020, smoothing their net financial accounts. In both countries there was a contraction in net flows in 2020. However, in Chile liability flows decreased and asset flows increased in 2020 compared with their levels in 2019, while Colombian flows showed the opposite behavior.

In the case of Chile, nonresidents abruptly brought their money home in 2020. Liability flows were significantly below their level from the year before, representing what is known in the literature as a sudden stop in liability inflows.

Despite Chile’s sudden stop in liabilities, residents brought money from abroad in the last two quarters of 2020, as we can see in Figure 1, Panel A. Interestingly, this inflow from residents compensated the outflow from nonresidents, producing an “offsetting behavior” that prevented a more damaging sudden stop in net flows.

Chileans’ Retirement Accounts

Where did this money come from? It came from Chilean’s private pension funds, that is, from their own retirement accounts, which are partially held abroad. In July, and December of 2020, the Chilean Congress enacted laws allowing people to withdraw up to 10% of their retirement accounts each time, looking to give liquidity to families during the COVID pandemic. By the end of 2020, the withdrawals from retirement accounts reached a little more than US$31 billion (about 12% of GDP). (Another round of withdrawals was authorized in 2021 and more are still being discussed in Congress.) Thus, it was the exceptional access to foreign assets during a time of duress that prompted Chileans to bring money back from abroad.

In Colombia, net flows also decreased in 2020 but not as much as in Chile (see Figure 1, Panel B). However, residents sent much more money abroad in 2020, compared with 2019, creating what is known as a sudden stop in asset outflows. Mirroring Chile, Colombia showed the opposite offsetting behavior where the performance of liabilities prevented the sudden stop in assets from becoming a sudden stop in net flows. In fact, liability inflows to Colombia were bigger in 2020 than in 2019, and they were significant in the fourth quarter, when residents were saving the most abroad (Figure 1, Panel A).

The last quarter of the year was remarkable due to the IMF flexible credit line (FCL). FCL is a credit line for crisis prevention and crisis mitigation, available only to countries the IMF assesses as having a strong policy and economic framework. In December of 2020 the Colombian government drew $5.4 billion (about 2% of its GDP) under the FCL, helping its budgetary response to the pandemic. In addition, other nonresidents besides the IMF kept their lending to Colombia at roughly the same level as in 2019.

The Colombian Government’s Deposits Abroad

Did locals run for the hills while foreigners came to the rescue? Half of the increase in Colombian resident’s outflows in 2020 came from general government investments in the fourth quarter, according to balance of payments data. It turns out that the Colombian government deposited the FCL disbursement in a foreign account and took a little while to put those funds to use. Hence, locals didn’t rush to take their money abroad. Rather, the government (a resident) received a significant loan as a deposit abroad and took some time to spend it.

To sum up, the COVID pandemic strained external financing flows into Latin American and Caribbean economies, even those with strong fundamentals. While the outcomes in the case of Chile and Colombia seemed opposite, they both reflected government measures to exceptionally tap unconventional financing sources. This highlights the importance of understanding the macroeconomic context when viewing financial account flows, especially when considering 2020 data.

Leave a Reply