John Kay’s column in the Financial Times is always an interesting read. In one of his last columns (ungated here) he pungently questioned the pertinence and value of Cost Benefit Analysis.

His point: if the London sewerage system had been subject to present-day Cost Benefit rules it would never had been built. The Thames would still be a fetid cesspool and leisure walkers, distracted tourists and Treasury mandarins would not have been able to enjoy the wonderful Embankment views from the Queen’s walk in the South Bank.

According to Kay, the civil servants of the time (good to remind one-self that the Her Majesty´s civil service is also a Victorian creature) would have been required to analyze the impact of the stench on property values and health, in an era when medicine was still a scary combination of chance, quackery and torture, and when the urban terror that was the 1854 cholera epidemic had only very recently been attributed to polluted waters.

Even if they had read Jules Dupuit, the French engineer who is generally considered the father of Cost Benefit analysis,

Their estimates would have been completely wrong and irrelevant anyway. The salient fact is that London could never have become a great business and financial capital if its residents felt an urge to vomit every time they went outdoors.

Although (economists always have two hands)

It is perfectly proper to demand a detailed rationale, and quantification of that rationale when quantification is possible. Specific quantification is often bogus, however, and beside the point; there would have been no modern world without railways or with the great stink.

Is Kay right?

No.

With 20/20 hindsight it is not hard to come up with a long list of transformative projects and endeavors that might not have passed the Cost Benefit muster. The London sewers are not the only one. One could add to the list the discovery of the Americas, where the objective was to find a trading route and a brand new Continent was found.

No Cost Benefit assumption would have figured that one out. Or the Great Wall of China which receives over 2 million visitors a year, although its builders had the exact opposite objective in mind: to repel uncivilized foreign hordes.

But all this is hindsight 20/20.

Imagine that Mr. Kay had been born in Equatorial Guinea where President Teodoro Obiang’s vision of a new capital – Oyala – is estimated to cost US$1.3 Billion. Oyala will house 200,000 Guineans (out of a current population of 700,000), come fully equipped with a six lane highway (the Avenue of Justice) and a golf course carved out of the virgin jungle.

Who knows if the myopic Cost Benefit analysis vision might have missed the future African Dubai? Or maybe the African Dubai title will be contested by the publicly funded $3.5 billion Nova Cidade de Kilamba in Angola which anxiously awaits its first tenants.

But let us not be that ambitious. One can think of countless hospitals, roads, highways, airports, and yes sewer systems that stand idle and gather dust because nobody bothered to understand if anybody needed them or would use them. And that is the basis for Cost Benefit analysis.

Kay is answering the wrong question, which is rhetorical at best.

The question is not what one giant watershed transforming project can do for your country and answer it with the lens of history. The real question rather is how can you combine knowledge and hard data so that the thousands of future projects that represent no welfare gain and that will burden the public budgets for years, are simply not funded, without the benefits of hindsight.

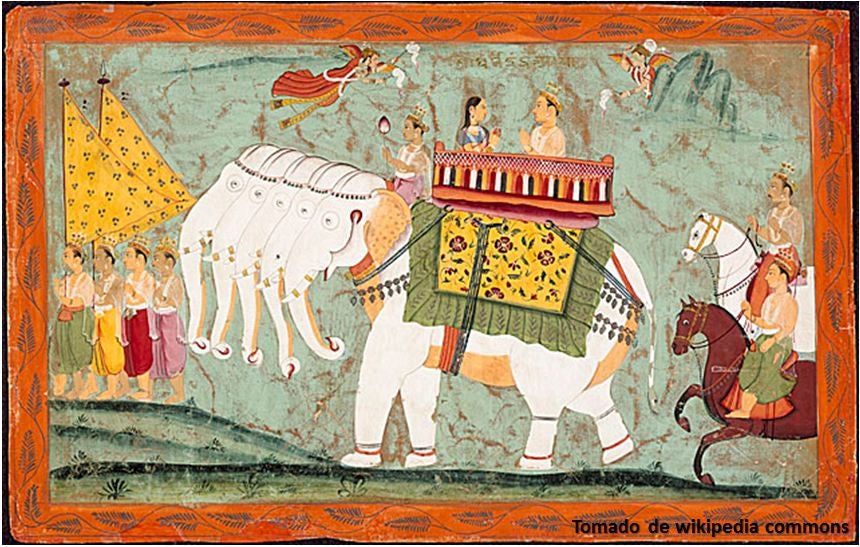

And we even have a name for them: white elephants, some bigger than others.

White elephants not only extract social surplus from where there is not much to start with, they also act as a perverse and inefficient redistribution mechanism, where it is precisely that inefficiency which makes them attractive to some politicians who are in a unique position to benefit politically from them.

After all, any politician can take credit for a reasonable project, but only transformative leaders that have a grand vision go into the history books.

Irony aside, there are, tragically, too many white elephants to count.

Leave a Reply