Inequality in Latin America has increased during the pandemic. That is our conclusion in a forthcoming study in which we noted that 2020 saw a reverse in the trend toward poverty reduction and greater equality that started 20 years ago.

The study is based on data generated through employment and household surveys conducted over the past three decades. For 2020, information comes from 10 countries – accounting for approximately 75 percent of the population of the region – that serves as the basis for determining the most recent trends.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to produce results based on primary data collected by national statistics institutes during the pandemic.

Historical Overview: 30 Years of Inequality

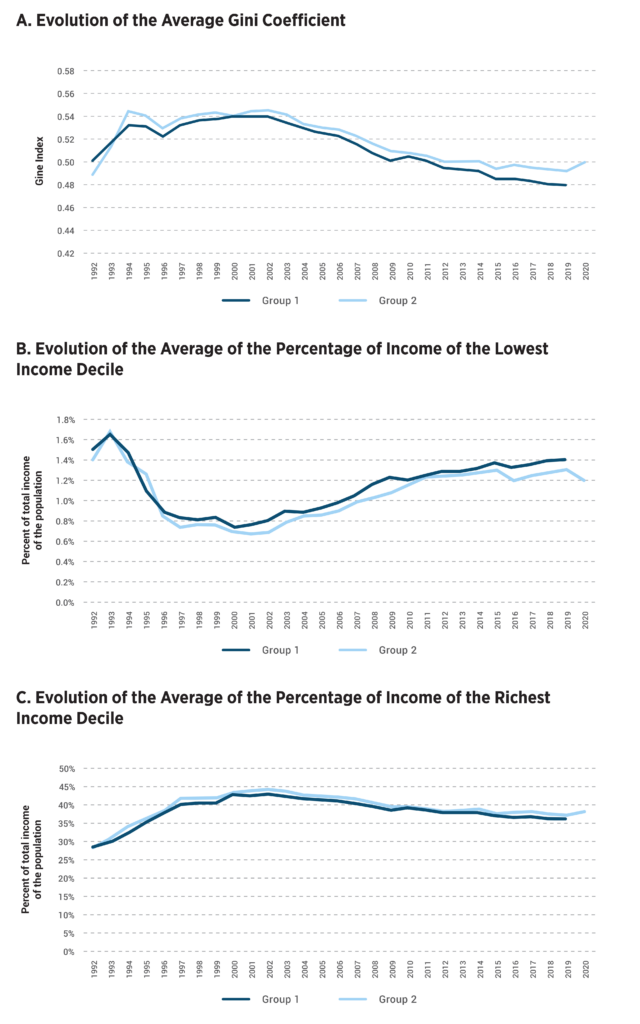

Panel A of Figure 1 presents the evolution of the average Gini index calculated for the 16 countries of Latin America for which a consistent series of household surveys is available for the period 1992–2019 (labeled as Group 1).

This series is probably the longest and most updated available in the region, covering almost 30 years.

Figure 1. Trends in Inequality in Latin America from 1992 to 2020

According to our calculations, between 1992 and 2002 the Gini index increased by almost 10 percent, reflecting an increase in inequality in the region. Starting in 2002 there was a tipping point after which inequality decreased for almost two decades.

In 2019, the region experienced the lowest level of inequality in the past 30 years.

Panel B shows the evolution of income for the poorest 10 percent of the population and Panel C shows the evolution for the richest 10 percent. The figures demonstrate that average inequality was reduced between 2002 and 2019 thanks to the increase in relative income of the population with the fewest resources and the lower share of total income of the richest decile.

The inequality reduction dynamic that started in 2002 was broken in 2020, which saw a 2 percent increase in the value of the Gini index.

Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, and Chile have the largest increases in inequality.

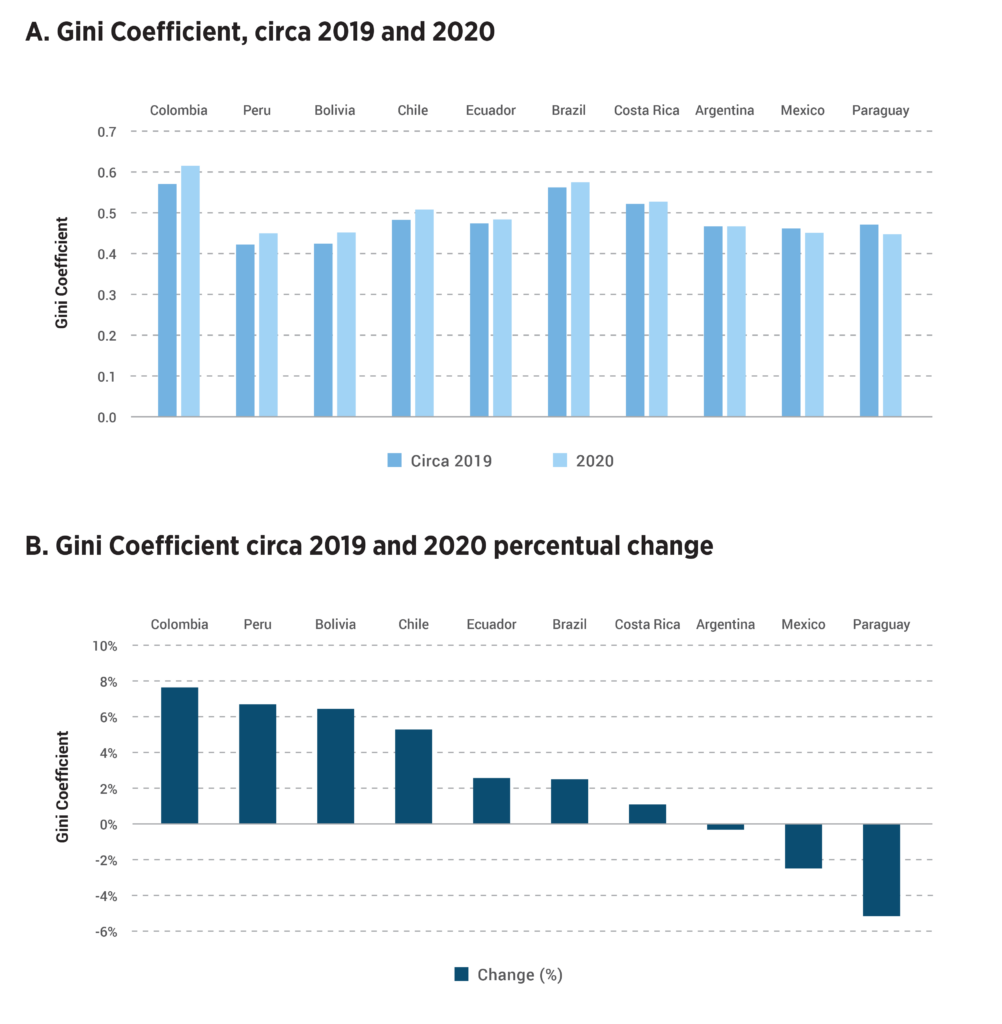

Figure 2 presents the changes for each of the 10 countries in Group 2 for which we have data.

In percentage terms, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, and Chile experienced the largest increases, with changes of between 5 and 8 percent on the Gini index between 2019 and 2020. They are followed by Ecuador, Brazil, and Costa Rica, with increases between 1 and 2.6 percent.

In Argentina, no change is observed, Mexico and Paraguay show an opposing trend, with Gini indices that fall by 2.5 percent and 5.2 percent, respectively.

Figure 2. Gini Coefficient in Latin American, 2019-2020 (selected countries)

Note: For Chile, the data are for 2017, and for Mexico, the data are for 2018. For the remaining countries the data prior to the pandemic for which there is information is for 2019.

What Is Behind Inequality?

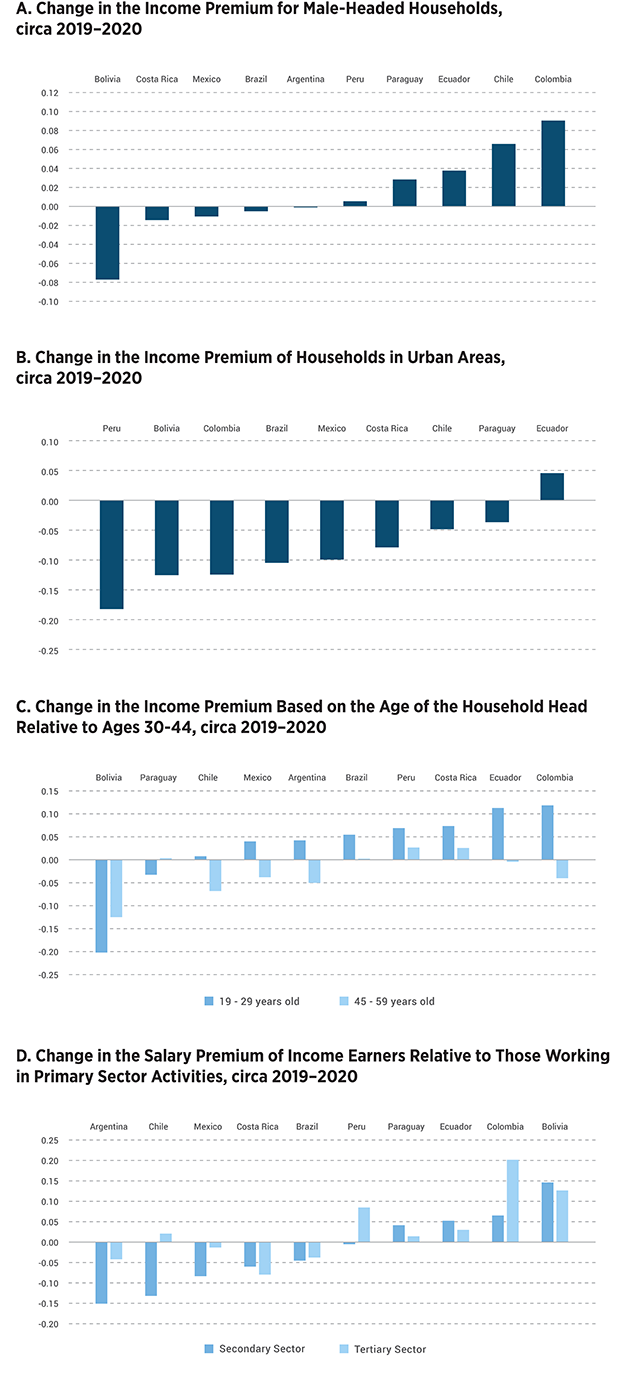

In exploring the increase in inequality by gender, age, occupational sector, or other characteristics, we see a mixed picture.

In Paraguay, Ecuador, Chile, and Colombia, male-headed households saw increases of between 2 and 10 points in their income premium relative to female-headed households. In Bolivia, the differential by gender widened considerably by nearly 8 percent (panel A of Figure 3). In Costa Rica, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Peru, the gaps remained almost constant. These results are net of the changes in the differentials by age, location of residence, and educational level.

Figure 3. Change in the Value of the Per Capita Income Premium by Characteristics of the Household Head between 2019 and 2020

With the exception of Ecuador, the income differential between urban and rural areas was reduced (panel B of Figure 3), and in half of the countries analyzed households with heads in the 45-59 year-old age group suffered more than households with heads of a younger age (panel C pf Figure 3).

Mixed results are seen in terms of occupational sector (panel D of Figure 3).

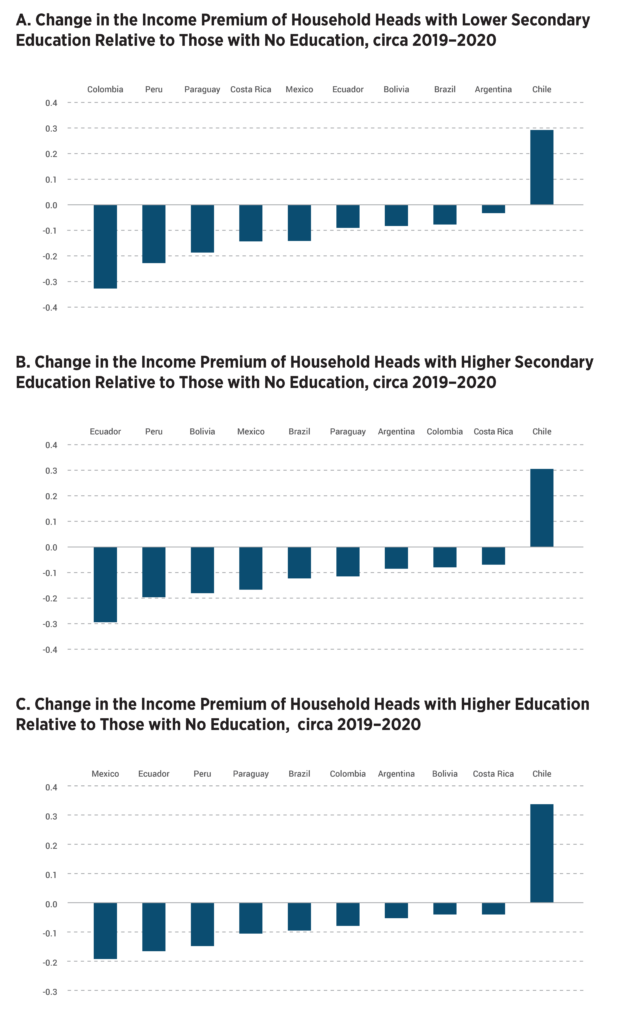

Income differentials by education level declined between circa 2019 and 2020 in all of the countries except Chile (Figure 4), but the more educated suffered to a lesser extent.

Figure 4. Change in the Value of the Per Capita Income Premium by Education Level of the Household Head, between 2019 and 2020

Note: In the case of Argentina, the coefficients are relative to those with primary education.

In conclusion, on average an increase in inequality is observed, although there are differences by country and mixed results by gender or age of the household head, urban or rural residence, and sector of economic activity. Income differentials by education level were reduced in most of the cases.

Although a deeper investigation could delve further into the role of public policies and/or remittances in mitigating the negative impact of the pandemic on those who are most vulnerable, the analysis of the household surveys confirms the estimates of several previous studies based on projections of the possible effects of confinement in income distribution.

Leave a Reply