Does it happen to you that you carry an umbrella almost always in case it rains, and never need to use it except -of course- when it’s raining, and it’s precisely then that you realize that you forgot it? Isn’t it the case on any given day walking outside, that we are willing to pay more for an umbrella when it is pouring than when it is sunny? The umbrella is a device that prevents us from getting wet on rainy days, just as car or medical insurance prevent us from going bankrupt if we have a big accident or get seriously ill.

Something similar happens in financial markets between governments and sovereign lenders. Governments borrow from private creditors to close their financing gaps. However, if they run into difficulties, private creditors tend to turn their backs on them and stop lending, making even worse an already difficult situation. But, when private investors stop lending, can Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) help fill the financing gap? If this is the case, will MDBs keep disbursements regardless of the source of the problem?

These questions are important to understand the role of the MDB system within the International Financial Architecture, as MDBs are a relevant source of public finance, especially in low and middle-income countries where their disbursements are larger and less volatile than flows supplied by private agents. This role as financing providers has made MDBs key for the execution of fiscal policy, especially in lower income countries.

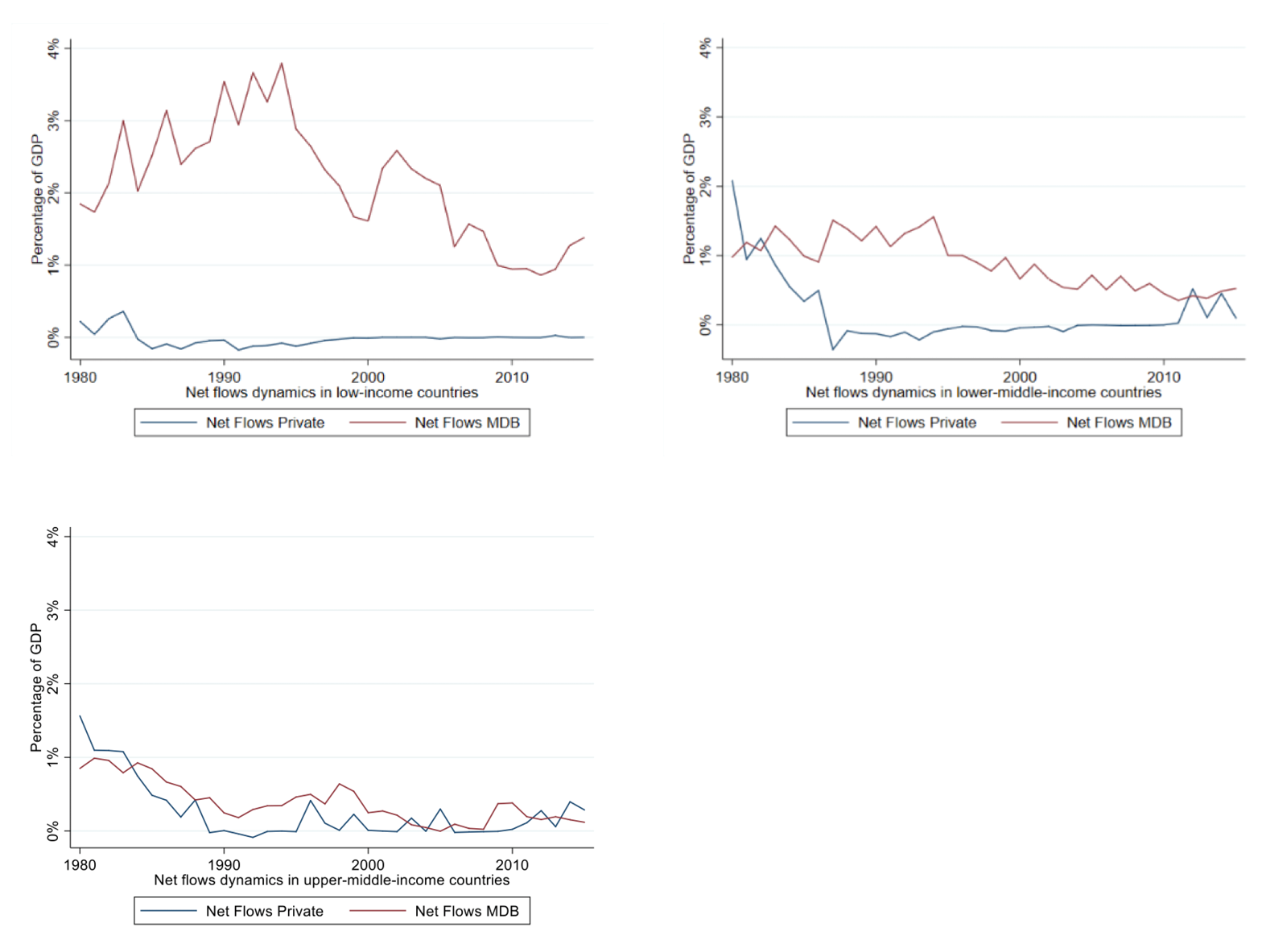

Figure 1. Dynamic of Net Flows by Income Groups

Notes: The figure shows the trends of median net flows scaled by GDP for upper-middle-income, lower-middle-income, and lower-income countries. Net flows are disbursements net of principal repayments. The sample period is from 1980 to 2015.

In a recent paper, we assess the behavior of MDB lending to the government when it rains, that is, during fiscal crises in a sample of 108 low and middle-income countries that we observe during 1980-2015.

During these events, governments experience a significant decrease of private sector financial flows, but no change in flows from MDBs. Furthermore, we find differences in the response of private creditors and MDBs if we distinguish between different types of fiscal crisis (as defined in Gerling et al. 2017).

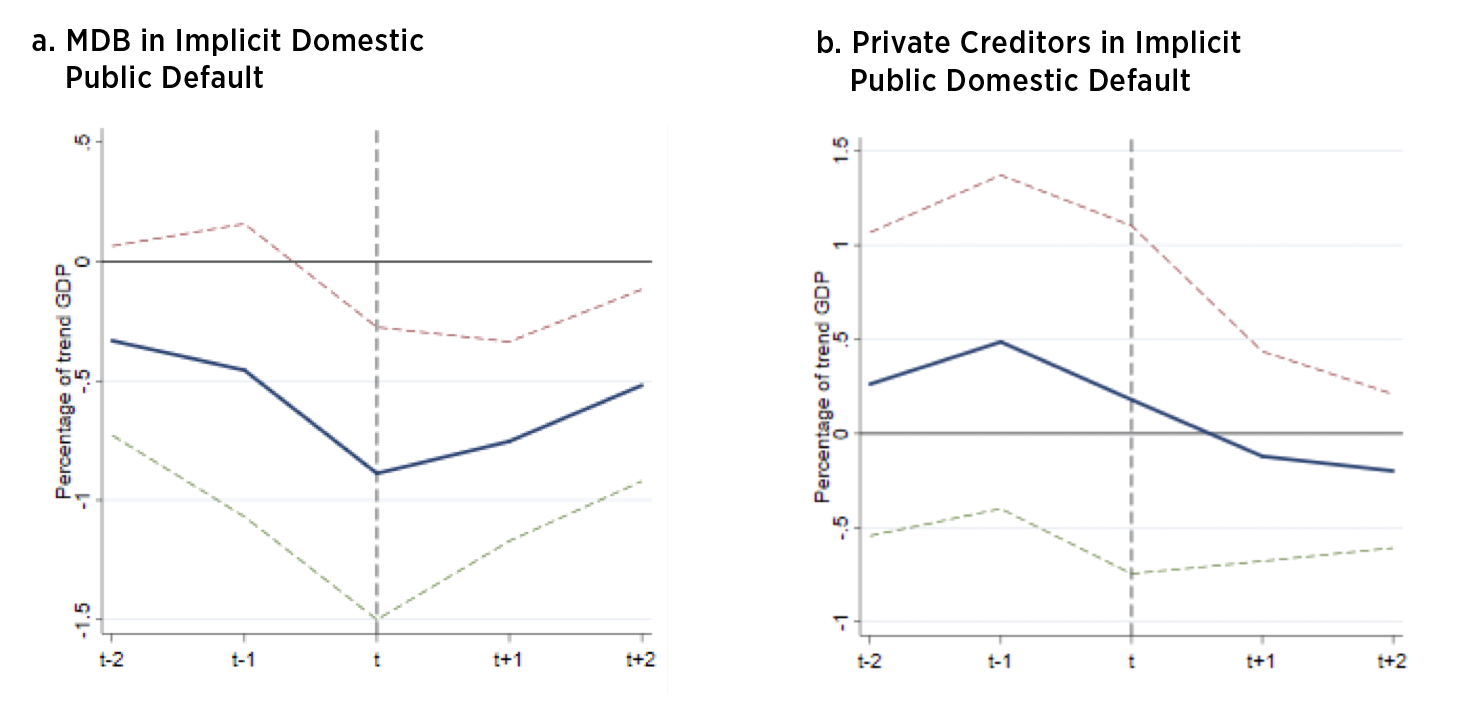

For example, all the MDBs significantly decrease their lending in implicit domestic public defaults, in other words, when countries are experiencing difficulties to honor their payment obligations and run domestic payment arrears or print money to finance their budget causing high inflation.

Figure 2. Net Flows in Selected Fiscal Crises by Type of Creditor

Notes: This figure shows the evolution of capital flows around implicit domestic public defaults by plotting the behavior of net flows by MDBs or private creditors in 5-year windows around crisis periods, with confidence intervals at 10% significance level. Net flows are disbursements net of principal repayments and are scaled by trend GDP. The sample period is from 1980 to 2015. MDB: multilateral development banks.

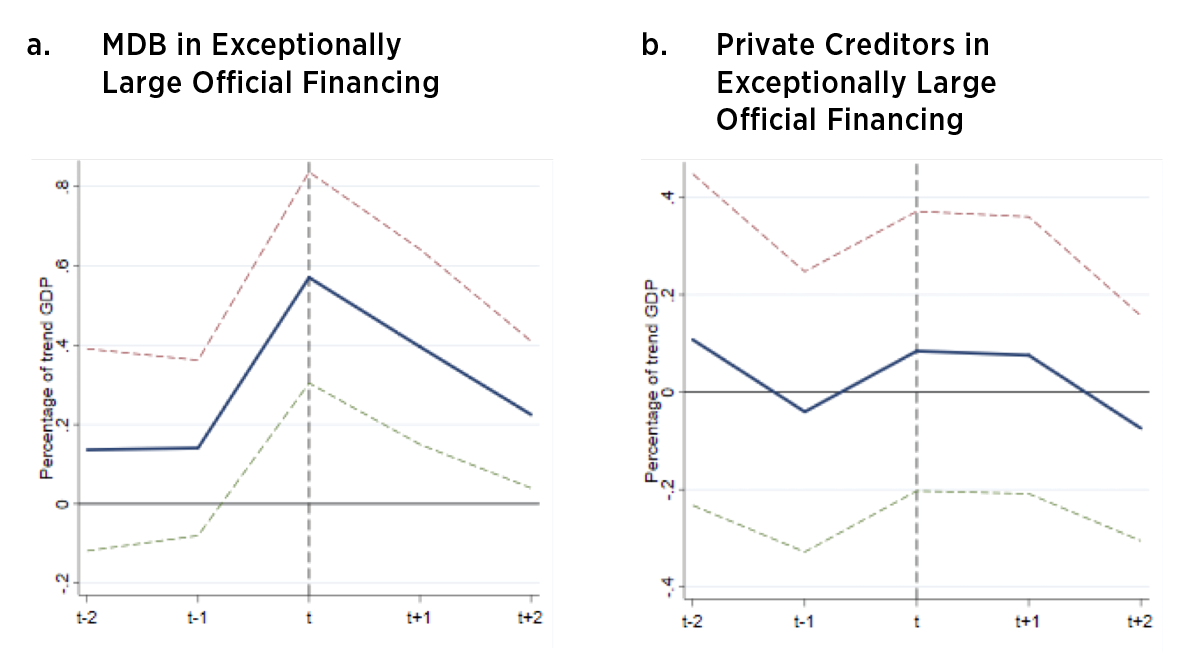

But in crises that are followed by exceptionally large official financing, in other words, when countries ask for support from the IMF with access above 100% of their quota and fiscal adjustment as a program objective, we find that all the MDBs join efforts to provide financing to governments. This shows synchronization among the international financing institutions.

Figure 3. Net Flows in Selected Fiscal Crises by Type of Creditor

Notes: This figure shows the evolution of capital flows around exceptionally large official financing crises by plotting the behavior of net flows by MDBs or private creditors in 5-year windows around crisis periods, with confidence intervals at 10% significance level. Net flows are disbursements net of principal repayments and are scaled by trend GDP. The sample period is from 1980 to 2015. MDB: multilateral development banks.

Finally, when a country experiences loss of market confidence or a credit crisis and private flows decrease, MDBs do not decrease their support to the country affected.

In sum, MDB lending works like the umbrella in rainy days as they provide funding to governments during fiscal crises. In cases in which it is not raining but pouring (severe crisis in which the IMF steps in), MDBs still work as a system and provide funding to struggling governments.

Leave a Reply