Before Peru was struck by COVID-19, Diana Quispe* was a part-time hairdresser based in the outskirts of Lima, who served customers in their homes in one of the city’s wealthier districts. She was an informal sector worker, like almost 80% of workers in Peru and over 50% across Latin America, with no health insurance or paid sick leave.

But when the government announced strict lockdown measures at the onset of the pandemic it was clear that her job —which required close contact with customers— was not going to be viable for some time. It was the case for many workers in personal services who make up a large part of the informal sector.

As an informal worker and the mother of three, Diana Quispe had to make a difficult decision: either look for another informal job and disregard the authorities looking to sanction those who evaded lockdown, or rely on her partner’s income as a primary-school teacher. As her 7-year old boy started online schooling and she became afraid of exposing her mother to the virus from looking after her two toddlers, like many women in her position, she made the tough decision to stay home and care for her children, instead of looking for another job.

In most economic crises in Latin America before the pandemic, the informal sector has traditionally functioned as a buffer, absorbing the workers leaving the formal sector and limiting increases in unemployment. People leaving the formal sector would reinvent themselves in the informal sector as a means of survival.

But this crisis has been unlike the previous ones.

At least for the first half of 2020, labor market dynamics observed in past crises, simply did not occur. Like Diana Quispe, a greater proportion of the economically active population left the labor market and became inactive, with most of the jobs lost corresponding to the informal sector.

What we found is that formal jobs didn’t decrease as much. Several reasons might explain this. Due to the uncertainty about the duration and depth of the health crisis, some employers might have preferred to reduce the hours of activity per job instead of reducing the production plan in order to avoid firing costs, and several governments provided support to keep firms afloat during the crisis.

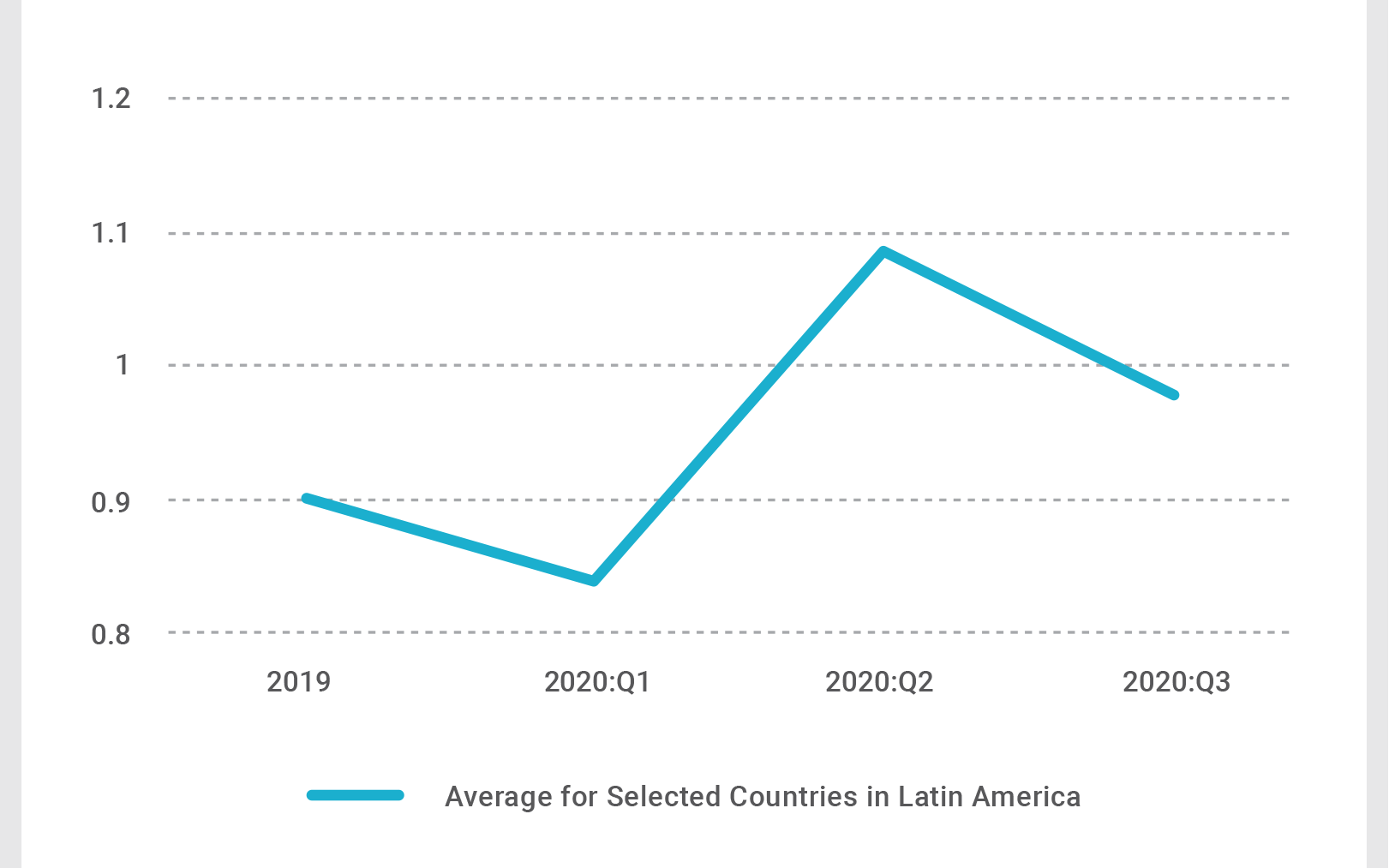

For the nine Latin American countries in our study, we found that formal employment grew relatively to informal employment (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Share of Formal Jobs Versus Informal Jobs

Estimates from household or employment surveys: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru. Formal is defined as having access to social security. The survey for Argentina has urban coverage only.

On average, between the first and second quarters of 2020, the ratio of formal to informal employment increased from 0.84 to 1.09, with the most pronounced changes in Argentina, Chile, and Brazil (Figure 2).

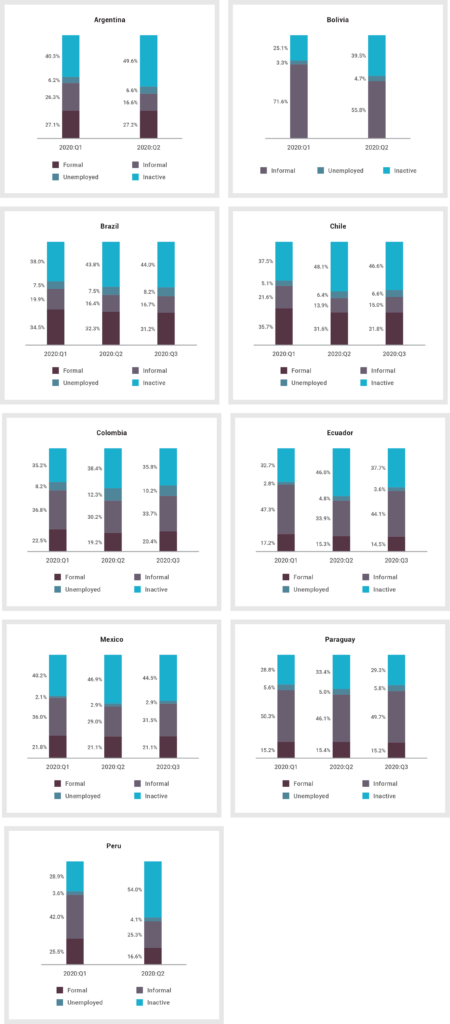

Figure 2. Distribution of the Working-age Population over 15 Years Old, Selected Latin American Countries, 2020 (percent)

Source: Acevedo et al. (2021).

A large share of people exited the labor force, leading to large increases in inactivity: from around 5 or 6 percentage points in Paraguay, Brazil and Colombia, to around 15 percentage points in Bolivia and 26 in Peru.

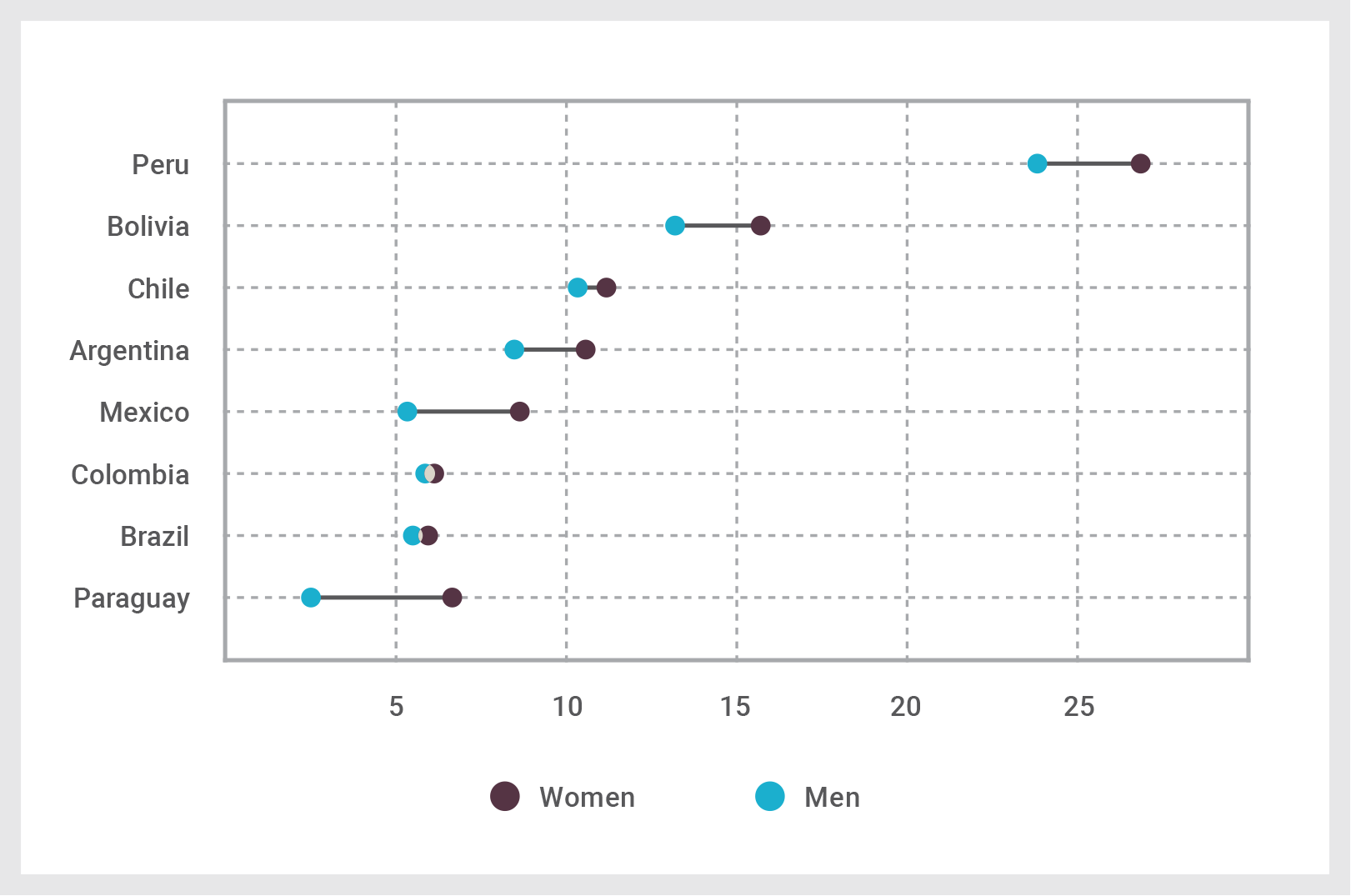

In most countries the increase in the share of inactive workers was driven by women like Diana Quispe (Figure 3, panel a). Globally, women are overrepresented in many of the industries hardest hit by COVID-19. Forty percent of all employed women—510 million women globally—work in hard-hit sectors, compared to 36.6 per cent of employed men.

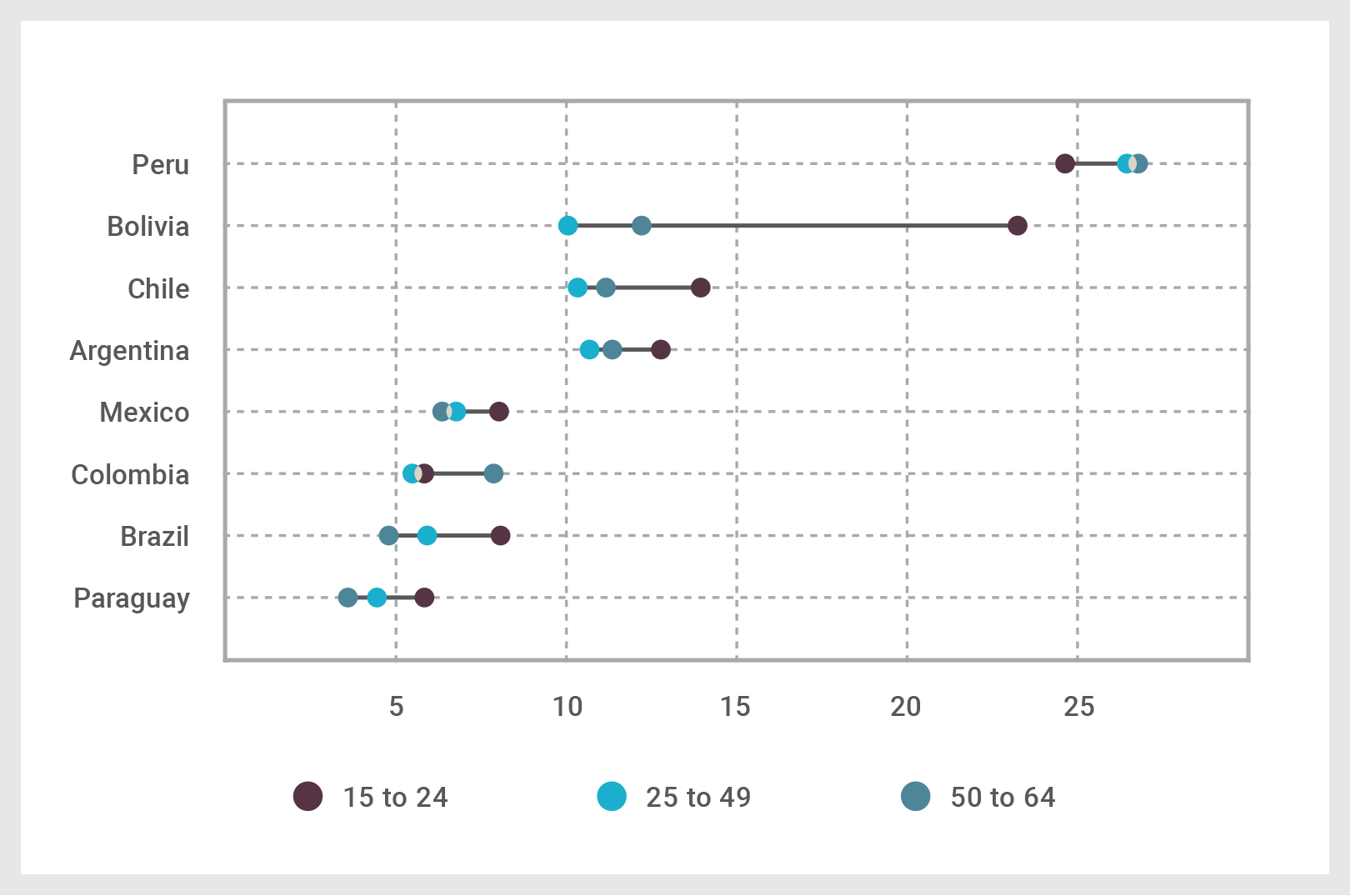

Young people (Figure 3, panel b) were also heavily impacted by the pandemic and many were forced to stay home with severe consequences for their future. The lower likelihood of obtaining employment might discourage their job hunting, potentially contributing to the millions of inactive youth in Latin America who are neither looking for work nor studying.

Figure 3. Increase in Share of Inactive in 2020, between Q1 and Q2 (percentage points)

| a. Increase in share of inactive (percentage points), by gender |

|

| b. Increase in share of inactive (percentage points), by age |

|

Source: Calculations based on Acevedo et al. (2021).

Note: Formal is defined as having access to social security. The survey for Argentina has urban coverage only.

These results are in line with findings by the International Labour Organization (ILO) (2021), which argues that the changes in the labor market during the pandemic are not reflected in higher unemployment rates.

Instead, due to mobility restrictions and confinement measures, a large proportion of the employed population decided to leave the labor force altogether, or at least temporarily. Instead of the informality rate increasing, the rate of inactive people increased, which means that people stopped looking for work.

Interestingly, in other regions of the world, the adjustment patterns have been different. In Asian countries, for example, the pandemic seems to have triggered an increase in informality.

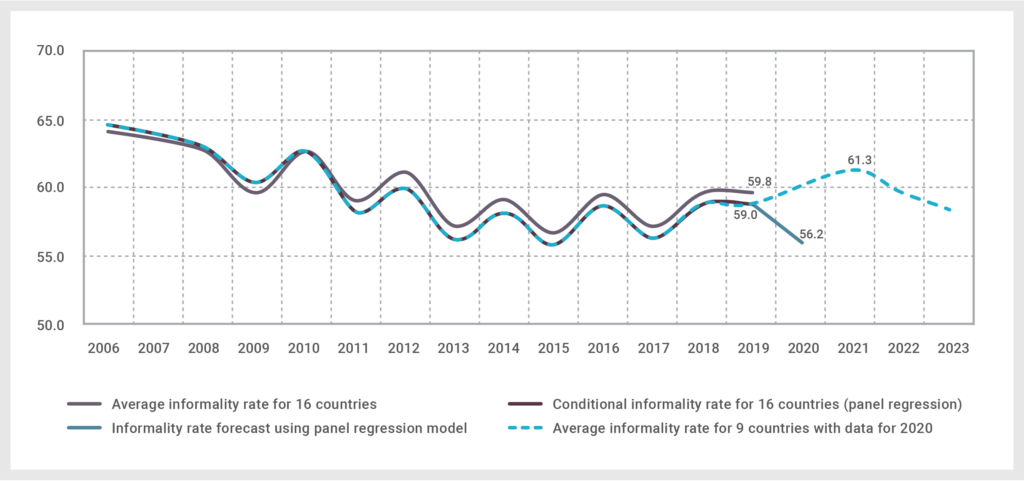

However, these dynamics are unlikely to persist over time. Our study projects that starting this year, informality will grow to levels higher than those of the pre-COVID-19 era—with 7.56 million additional informal jobs—as a result of the population returning to the labor market to compensate for the declines in incomes (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Latin America: Simulation of the Informality Rate (percent)

Source: Acevedo et al. (2021).

Note: The blue line represents the average informality rate in 16 countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay); the red line is the informality rate predicted by the model in the paper; and the yellow line presents the drop in the informality rate between 2019 and 2020 in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay and Peru.

Therefore, if we want to reduce informality in the region, we must adopt the right public policies.

Our study focuses on the benefits of a few of them and finds that postponing or forgiving income tax payments and social security contributions conditional on the generation of formal jobs could reduce the growth of informality by 50 to 75 percent.

Educating the labor force would also have the potential to reduce informal work by 50 percent. Policies such as support for access to childcare services, online training schemes, access to microcredit for entrepreneurship, or job search assistance mechanisms for youth could be explored as options in this regard.

Informality in the region might be about to rear its ugly head. If we want to stem its growth, we must take action now.

*Diana Quispe is a fictional character created for this article to better explain the findings of this article. This character combines characteristics of many working women in the region.

Leave a Reply