Most people’s social interactions take place in their neighborhood. This is where girls, boys, and young people form their preferences and opinions about others. It is also the place where social norms are regulated. As a result, how individuals value education and its expected benefits is influenced by the values and norms of the neighborhoods in which they live. What is the scope of such influence?

An IDB study for the city of Montevideo, Uruguay, quantifies the neighborhood’s impact on the number of years of education (for young people aged 15-24), on the decision to enroll in secondary school (for teenagers aged 15-18), on the likelihood of having completed secondary education (for young people aged 19-24) and on the decision to enroll in university (for young people aged 19-24).

What Is Neighborhood Educational Impact?

The neighborhood educational impact is the influence that people’s place of residence has on their decisions and academic outcomes. Suppose we take a sample of similar individuals and randomly assign them to different neighborhoods. Will they make the same decisions? Will they achieve the same level of education? The neighborhood effect is the difference, positive or negative, caused by one’s area of residence.

Understanding the neighborhood’s impact is relevant in Latin American cities characterized by significant residential segregation. Highly educated and wealthy neighborhoods are very close to impoverished and violent neighborhoods. Educational disparities and the impact of one’s place of residence can create vicious circles in a segregation dynamic.

Neighborhoods And Education In Uruguay: High Inequality And Low Convergence

Using Continuous Household Surveys from Uruguay between 1992 and 2019, the study shows that, in Montevideo, there is a high inequality of educational results between neighborhoods according to income level. High-income neighborhoods have secondary school graduation rates of up to 90% and university enrollment rates of more than 70%. In middle-income neighborhoods, these values can drop to less than 70% and 50%, respectively, and are even lower in low-income neighborhoods where the secondary school graduation rate can reach levels of only 20% and university enrollment does not reach 10%.

A relevant question to understand the evolution of this geographical inequality is whether neighborhoods with the lowest initial indicators eventually improve and converge to the educational indicators of the most educated neighborhoods.

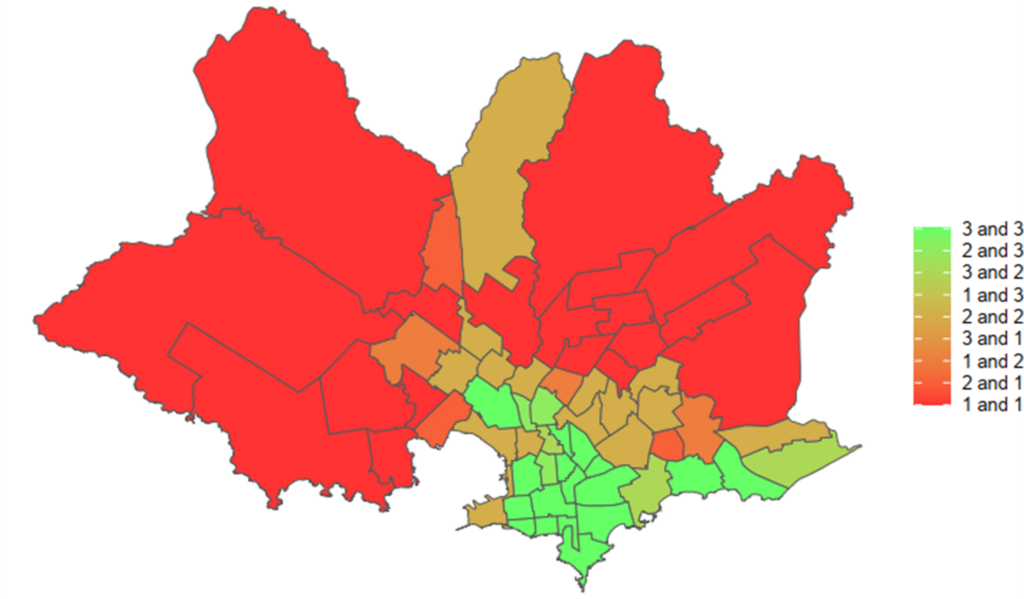

The study compares indicators from the 1990s and 2010s. It classifies neighborhoods into three groups: group 1 with negative effects (lower third), group 2 with medium effects (between the 34th and 66th percentiles), and group 3 with positive effects (upper third).

A traffic light map was created to help visualize the results. Red represents neighborhoods that experienced more negative situations in the 1990s and continue to do so. The green neighborhoods showed the best results and remained that way.

Figure 1 shows the results in years of formal education after controlling for young people’s and their families’ demographic characteristics. Neighborhoods associated with poor educational outcomes in the 1990s tend to remain associated with poor educational outcomes in the 2010s. The opposite is true for better-performing neighborhoods. This demonstrates a high degree of geographic and temporal dependence; that is, the convergence discussed at the beginning of the paragraph occurs in only a few neighborhoods.

Figure 1. Conditional Transition Matrix (1990s-2010s)

Years of Education (15-24)

Better Educated Neighborhoods, Better Outcomes For Young People

While informative, the preceding analysis is not causal. Families are not randomly assigned to the neighborhoods they live in. On the contrary, they tend to choose to live in areas where people share their interests, values, or conditions, even when this decision is influenced by other factors such as the availability of transportation or the cost of housing. Given that housing costs should not directly impact educational outcomes, it is possible to use rental prices as an instrumental variable and thus measure the causal effect of residence neighborhoods on education.

Using the average educational level of adults residing in the neighborhood as a variable to measure the effect of the neighborhood, the study finds that the neighborhood is a relevant channel to explain the educational outcomes of young people and adolescents.

Several studies have found that having a more educated father or mother improves the outcomes of children. According to this study, an extra year of education for the head of the household is associated with a 10% increase in the adolescent’s years of education and a 2.7, 3.3, and 3.0 percentage point increase in the probability of enrolling in secondary school, completing secondary school, and enrolling in university, respectively. The neighborhood effect found in this study is approximately the same size as the effect of the education of the father or mother (head of the household) with whom a young person lives.

Who is the most affected? The study finds that men’s educational outcomes are more sensitive to their neighborhood and that household income, in addition to having a direct effect on educational outcomes, also has an indirect effect as a buffer for the neighborhood effect. In lower-income areas, households with a relatively better situation manage to mitigate the neighborhood’s negative impact.

Four Public Policy Proposals to Mitigate the Neighborhood’s Impact on Educational Outcomes

1. Public policies focused on geographic specificity

First, the disparity in educational outcomes across neighborhoods and the limited convergence (i.e., the low probability that a neighborhood’s educational outcomes will improve over time) suggest that policies focusing on geographic specificity may be more effective than uniform, centralized policies.

For example, an IDB neighborhood improvement program in Uruguay increased children’s primary school attendance by 30%. This increase, although related to infrastructure improvements, would also be related to improvements in families’ expectations about their and their children’s futures.

2. Extend the school day

Secondly, the persistence of this inequality over time suggests that regional educational policies must include a strong, active component. In this sense, extending the school day may be a viable option. Empirical evidence finds that extending the school day has a positive impact on academic outcomes, particularly for low-income students, in the poorest schools, and rural areas. Uruguay has implemented critical context school programs, which receive additional teaching resources and are usually full-school days. With IDB support, this effort, which already existed in primary education, is being expanded to secondary education through the María Espínola Centers.

3. Systems for early warning and trajectory protection

Another option is to implement tools that allow for monitoring school delays and repetition, as well as alerting about the risk of disengagement. Uruguay, supported by IDB, has pioneered the design and implementation of a Trajectory Protection System with early warning and support for students.

4. Communicate success stories that become role models

Finally, the impact of the neighborhood’s average educational level on the educational outcomes of adolescents and young people reinforces the convenience of communicating and disseminating success stories locally that can be used as role models to compensate for objective deficiencies in the neighborhood environment. For example, in Uruguay, an evaluation of an educational inclusion program in upper secondary education that included tutoring between reference students from the tertiary and secondary levels decreased school dropout levels.

Would you like to continue discussing educational inequality? Please visit this blog and leave a comment below.

Leave a Reply