A little over 30 years ago, when Amilcar Amaya was 13, he migrated with his family from El Salvador, leaving behind his native country amid a civil war in which 75,000 lives were lost and a fifth of the population was displaced.

In 1982, they settled in Valle de Paz, Belize, a community created to provide refuge for those who fled the Salvadoran civil war, as well as immigrants from Guatemala and Honduras. At the age of 16, Amilcar began work as a teacher at the Monseñor Romero Primary School and, since then, has devoted his life to supporting the integration and learning of successive generations, but not without first having himself experienced the challenges that language limitations and the social and emotional effects of migration pose for integration.

In recent years, stories like those of Amilcar have continued to proliferate in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), whether due to violence or persecution or, in the case of millions of people, in response to economic and social factors or natural disasters. Currently, like Amilcar, they are seeking to settle in different communities and find opportunities to improve their lives.

Many of the region’s countries, like Belize, guarantee the right to education and allow migrant children to enroll in their education systems, regardless of their migratory status. However, schools face administrative, financial and pedagogical challenges that, in turn, represent barriers to access for these students and their learning and integration. For example, in Belize and Guyana, where the official language is English, most immigrants speak Spanish or an indigenous language.

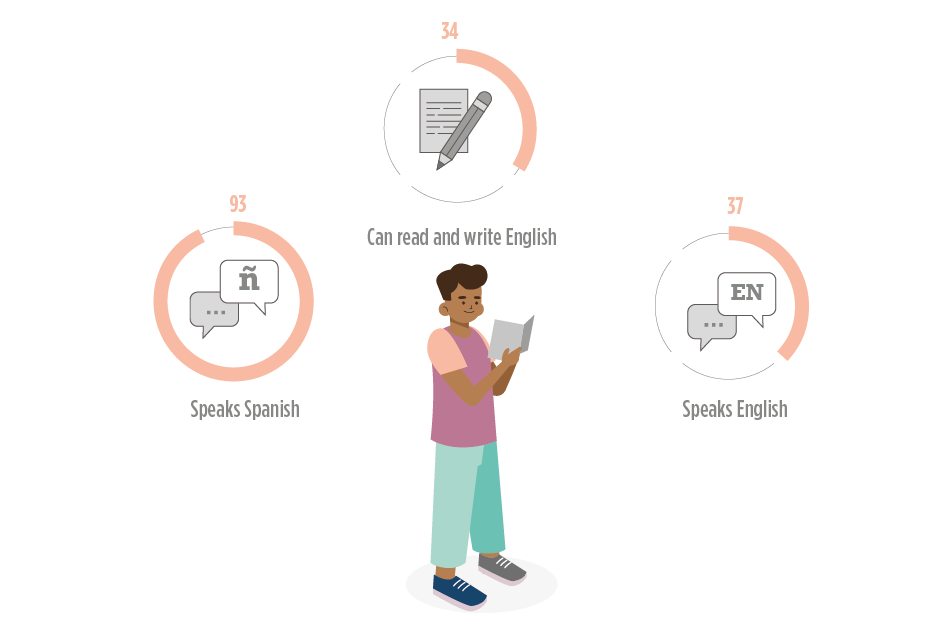

The IDB’s study of migrant and non-migrant families in Belize revealed that only a minority of migrant children speak, read and write English and, in general, have difficulty learning and communicating with their classmates and teachers.

Figure 1. Lower migrant average

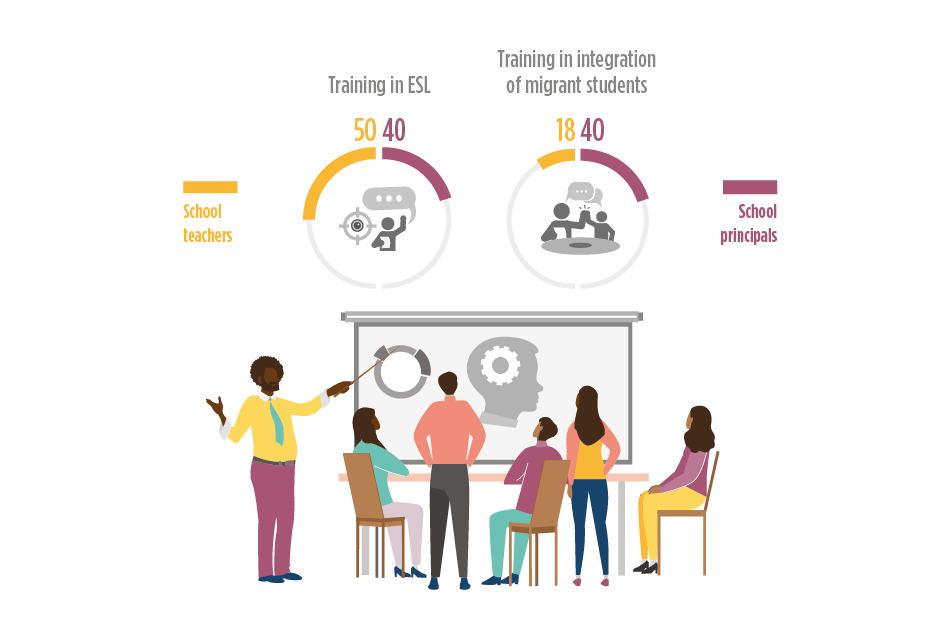

Teachers, for their part, also face challenges in integrating migrant students, both inside and outside the classroom. Schools do not usually apply diagnostic tests to assess students’ language or math skills and this makes it difficult to implement supportive or compensatory teaching strategies. They also lack the skills to manage multicultural learning environments so may, unconsciously, create situations of exclusion or rejection.

Figure 2. Training needs of schoolteachers and principals for multicultural environments and integration

Migrant students are victims of violence and racism

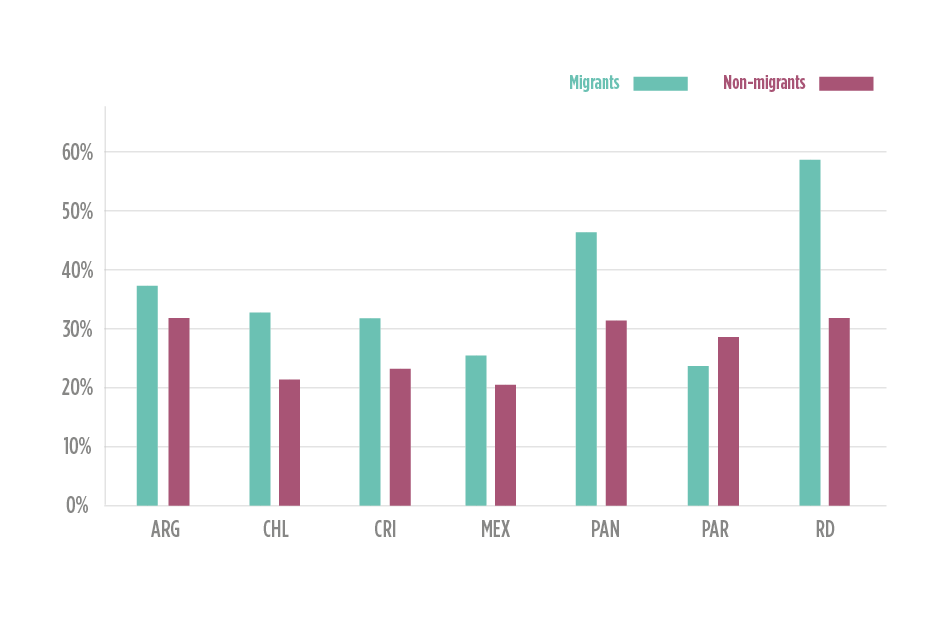

According to UNESCO’s TERCE test in Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Panama and the, the percentage of migrant children who are made fun of or bullied at school is higher than for non-migrant children. These situations, which range from racism and violence to differences in social and cultural customs, affect not only the children’s integration into their community but also their motivation and learning throughout their educational trajectory.

Figure 3. Percentage of children made fun of

Education is a vehicle that helps erase borders and, insofar as countries integrate migrants adequately, they become a positive force for their development.

At the IDB, we are supporting education systems in the region, such as those of Belize and Panama, with non-reimbursable investment funds, to strengthen their management through updated information and diagnoses about the challenges faced by the migrant and host population in their schools. In addition, these funds help to implement activities to eliminate barriers to access, learning and integration. These activities include:

- Teacher training on bilingual and multicultural education

- Development of catch-up materials

- Implementation of sports, artistic and scientific activities to develop citizen and socio-emotional skills

- Awareness campaigns and workshops to improve the school climate

- Equipment for schools, teachers and students such as electronic devices to facilitate ongoing education during the closure of schools because of the pandemic.

These activities benefit some 4,000 migrant children.

Tell us what you think in the comments section!

What can education systems in LAC do to integrate migrant students? What possibilities do you imagine for your school or education system?

I visited your site, it is really tidy and there is a lot of content. You can add some more pictures if you want.

really a good website a learn lots of things form this website thankyou to owner of this site.

Dear I want to take the time to thank you for posting such an amazing article on your website. It was good to see you take the time to write about something that you have experienced and understand fully. Best regards,

I like your writing style and appreciate your efforts. Having read this article, I am able to learn about Education without borders.

I like your composing style and value your endeavors. Having perused this article, I am ready to find out about Education without borders.

I agree with your point that there must be no discrimination when it comes to education and everybody has the right to receive just and equal education. Even a migrant student must not be discriminated against when it comes to receiving an education. Thank you for spreading this awareness about the importance of education for all. I will definitely share this article to make more people aware of this and share your message.

Muy buena página web claro que me gustarían unas buenas fotos adicionales.

Seguiré tu web frecuentemente.

Hi, I Read your article in which you mentioned this topic- Training needs of schoolteachers and principals for multicultural environments and integration seems to me very impressive topic and I think it must be implement in our Education system..

Thanks for this Article.