Of all the projections about the new normal in the aftermath of Covid-19, perhaps the one gaining greatest consensus concerns the need to design cities on a human scale.

To help recover from this pandemic, cities around the world are changing. How they conceive of public space and public safety, mobility and livability is being reconstructed. And how they stay competitive at international level, how they attract tourism and investment is being reimagined. Quality of life is now more essential than ever. Clearly, now is the time to permanently redesign our cities on a human scale.

Months before the pandemic, the Mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, sought reelection under the campaign slogan “a 15 minute city.” It speaks to self-sufficient neighborhoods, with shops, offices, sports facilities, schools and medical centres all within easy distance. It speaks too to accelerating sustainable mobility, and it follows the same trend seen in cities like Melbourne, with its “20-minute neighbourhoods” or Copenhagen’s Nordhavn, a “5-minute neighbourhood” which when completed is expected to set the standard for environmental, social and sustainable urban development.

As cities around the world emerge from Covid-19 confinement, modifying public space to allow for necessary social distancing is a top priority. We see this everywhere today, from Vilnius with its “open-air cafe” concept that allows restaurants and cafes to occupy space on sidewalks and plazas, to Domino Park, New York City, with social distancing circles painted onto the lawn.

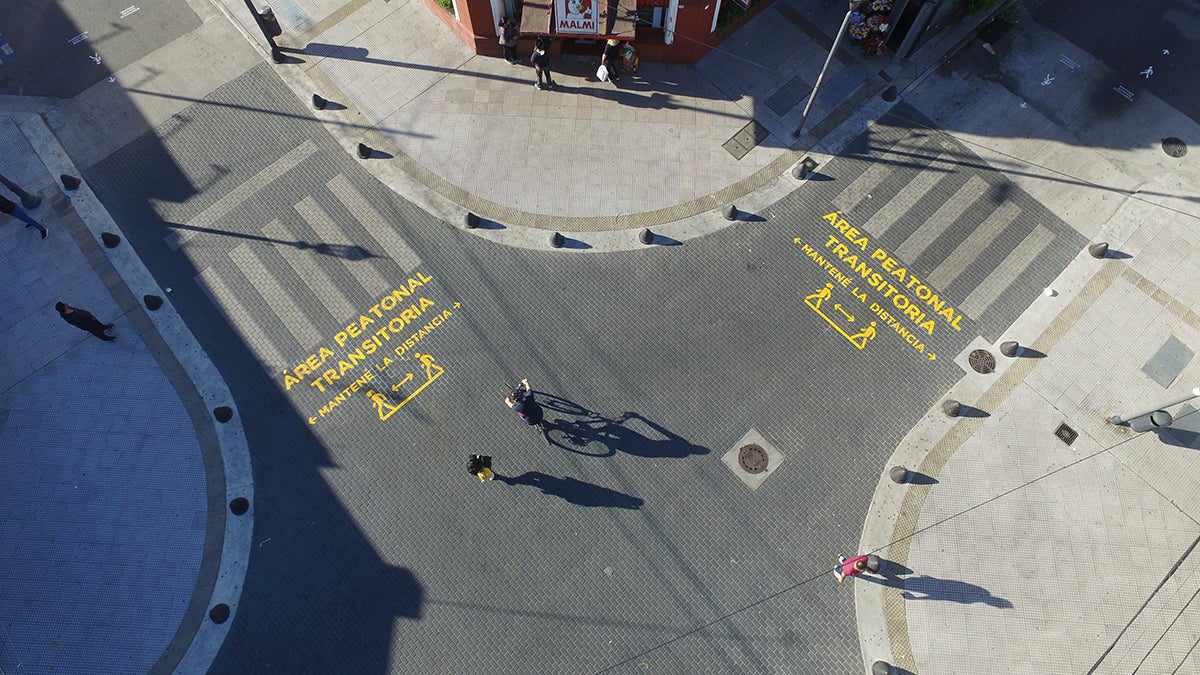

We see it too in changes to mobility. San Francisco has created “slow streets” that limit vehicle traffic and promote walking and cycling, and the city plans to add two to three slow street corridors of around 8 blocks each, every week. Milan is now planning to make temporarily pedestrianized streets permanent pedestrian thoroughfares. London is preparing to build a new cycling network to reduce overcrowding on the tube, trains and buses. Bogotá has added 80km of temporary bike lanes, with other cities in Latin America following suit. Many European capitals, like Paris and Barcelona, talk about ”post-car” cities. In Buenos Aires, as we gradually reopen our city, over 100 streets are being pedestrianized to avoid overcrowding and encourage commercial interactions inside the same neighbourhoods.

The vision that guides Buenos Aires’ Covid-19 recovery follows this trend of reimagining cities for people. The Urban Development Code of Buenos Aires conceives of a sustainable and efficient polycentric city, where businesses and services are decentralized, making it possible to live, study, work and play at a distance easily reachable by public transport, by bike or on foot. Already today, 4% of the hundreds of thousands of daily commutes in Buenos Aires are made by bike, along over 250km of bicycle lanes. Ten years ago it was 0.4%. All city residents are 15 minutes’ distance from a health centre. The city’s “microcentro” – its downtown area – has one of the largest vehicle restriction zones of any city centre in the world.

Urban mobility and design in its traditional sense, one that sees millions of people travelling daily from one end of the city to the other, may soon have its day. In this digital age, people value 30 minutes far more than they did 20 years ago. And as we gradually reopen our cities, they value 2 metres more than they did 3 months ago. Quality of life is less a desirable element of urban planning than it is an absolute necessity.

Some predict that in the post-pandemic new normal, people may refuse to live in large urban conglomerates with high population densities, thereby ushering in an era of de-urbanization. In Buenos Aires, however, we feel certain that city growth goes hand in hand with global development in the new normal. Cities can – and should – be better guarantors of quality of life provided they are safe and resilient, able to weather unexpected shocks. They will need to have good governance, agile enough to adapt essential services to meet the needs and safety of their citizens. They need adequate public space and more sustainable mobility options to enable people to move more efficiently and respect social distancing. All of these attributes are essential for a 15-minute city, just as they are essential to improving people’s quality of life, health and happiness.