Road safety is a critical development challenge and a top priority for governments across the developing world. Policymakers are implementing public policies for reducing the number of road crashes by 50 per cent by 2030, as committed in the SDG (Sustainable Development Goals) of Good Health and Well-Being. To achieve that target, we need to get the whole picture and understand how gender biases can influence road safety outcomes

By Laureen Montes – Valeria Bernal – Nicole Moscovich – Claudia Díaz – Eduardo Café

As discussed in the post A business case for road safety data with a gender perspective, road safety statistics tend to be presented as an average number, hiding disparities in the distribution of victims by gender, age and-or socioeconomic background. Indeed, global indicators shows that more men are exposed to car crashes. For example, men under 25 have almost 3 times more chances to die in a crash than women (World Bank, 2021). This can be directly related to the fact that women have less access to afford or use a private vehicle, as they are many times excluded from economic life, and they tend to be financially dependent, have lower incomes and low labor force participation. Also, it could be explained because women tend to travel shorter distances than men, commute less, and are not as exposed to road crashes as men.

Toxic masculinity and other gender biases that may affect road safety

International literature has demonstrated that gender stereotypes can play a significant role explaining driving behaviors. In fact, several papers stress that driving is usually related to a male activity from an early age, like if men have a natural gift compared to women. This perceived ability justifies many times the risk men take when they are on wheels. On the contrary, women are usually characterized as less talented and competent drivers. That is to say that they need to be more responsible to drive (IFSTTAR, 2018).

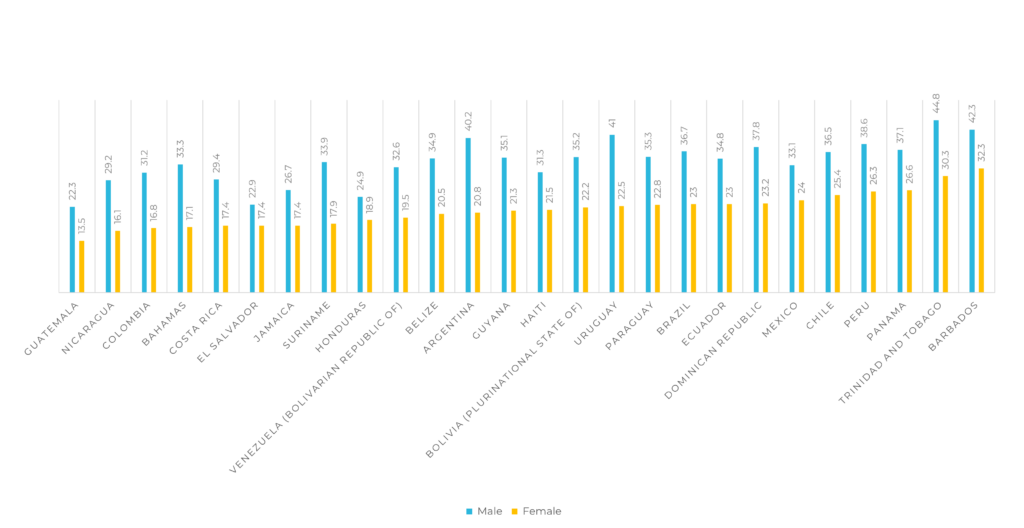

One example of these gender biases is reflected in the concept of toxic masculinities, which brings the idea of a set of beliefs and behaviors that men should follow to be man-like but are seen as hurtful. In the realms of road safety, toxic masculinity can be translated in behaviors such as driving under the effects of alcohol consumption (See Figure 1), high speeds, non-seatbelt use, which in turn can have an impact on the probability of road crashes.

*The alcohol-attributable percentage (AAP) denotes the proportion of a better outcome caused by alcohol (i.e., the proportion that would disappear if alcohol consumption were eliminated). Source: Based on WHO, 2018.

Even controlling for the fact that there are more male drivers, data still shows that women have a higher awareness of the risk and take better care of themselves: they consume less alcohol prior to driving a vehicle, declare less speeding when driving on the roads, respect more traffic light signals (both in cars and in motorcycles and bicycles), among other well behaviors (Argentine Road Observatory, 2021). These differences in risk perception/aversion can be a factor to understand the probability of road incidents caused by men and women, and therefore, provide valuable insights for the design of road safety interventions.

Despite the fact that men are less risk-averse and they have more crashes, the bias of women as less skilled drivers is reflected on insurance costs. The cultural belief is that women pay less but a study made in the U.S by the Zebra in 2020 showed that women payed up to 7.6% more than men depending on the state as gender and age are rating factor for car insurance. Seven states; California, Michigan Hawaii, Massachusetts, Montana, North Carolina and Pennsylvania have ban gender as a rating factor.

Another important gender bias is reflected in car designs, which can have a higher impact on women involved in road incidents. For example, programs to assess how cars perform during a crash are usually simulated with “neutral” dummies that represent male figures. This ignores the anatomic differences between women and men. In other words, cars are designed and tested for men’s bodies. As a result, women drivers are 17% more vulnerable to death in cases of road crashes. (Barry, 2019)

All these biases point out to the need of looking at road safety policies with gender lenses. Although women are, on average, are less affected by road fatalities, it is clear that the gender variable can be an important determinant for improving road safety for all. Decision-makers need to understand road safety issues from a gender perspective to design ad hoc policies to the different behaviors of men and women. Moreover, to reduce the impacts of road crashes we need to see the whole picture and the different impacts on each group, understanding their socioeconomic backgrounds, their culture, and behaviors at the wheel.

Road Safety in the Caribbean Region Course

Do you know that 18% of road crashes could be related to the quality of road infrastructure? Be a part of the change now, and let’s make safe mobility a reality! Learn about the current state of road safety in our region, its main challenges, and areas of action. Sign up in our open course.

REGISTER FOR FREE

Authors invited

Valeria Bernal. External consultant for the Transport Gender Lab of the Inter-American Development Bank. Architect from the Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana in Medellín and Master in Urban Planning and Policy Design from the Politecnico di Milano, her research has been focused on governance in public transport systems in Colombia. Her professional experience has been mainly linked to urban design and planning. Previously she worked as a project leader architect at the Agency for Landscape Management, Heritage and Public-Private Partnerships (Medellín), and with the Administrative Department of Planning (Medellín) where she participated in the formulation of the urban macro-projects of the MEDRío Strategic Intervention Area and the partial plans within it associated with the Land Management Plan, which obtained an honourable mention at the Colombian Architecture Biennial.

Nicole Moscovich. Public policy consultant, specialising in economic development, gender and data. Degree in Political Science (UBA) and Advertising (UCES). Master’s degree in Public Policy with a focus on economic development from the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella (thesis in progress). Diploma in data analysis applied to the development of public policies. She has extensive experience as a consultant for governments and the private sector. She has worked on issues such as Big Data, gender and labour market, productive development, data analysis for the development of economic diagnostics and impact assessment. University lecturer.

Eduardo Café. He has worked as a Consultant for the Transport Division of the IDB for four years and is now an independent consultant, working on projects for the air transport sector and safe urban mobility.

Very interesting point of view. I would like to add that, in terms of insurance and according to the statistics in Argentina, car accidents are much more serious when the driver is a man: there are more dead and badly injured people rather than in those accidents where female drivers are involved.