In memoriam Luiz Villela

The unexpected global economic crisis caused by the coronavirus (COVID-19) will have significant economic consequences. Faced with this outlook, Latin American countries are taking steps to mitigate the situation so that its consequences do not drag on over time. Some of these measures will involve increased spending on healthcare and transfers to vulnerable sectors. Together with the foreseeable drop in revenues, such steps will create even wider public deficits. In the short term these deficits will be financed by the growth of debt but, after the reactivation phase, in many cases the time will come for tax policy.

In our view, the measures to be adopted at that time should adhere to four guidelines:

- First, they must strengthen public revenues, since countries will have to return to the path of fiscal discipline.

- Second, they must not undermine the recovery, which is the ultimate goal.

- Third, they must not lose sight of equity; the crisis itself is regressive, so it is important to ensure that the escape from it is not also regressive.

- Finally, a clear distinction must be preserved between measures that are temporary and those that are permanent.

These four pillars entail a difficult balance, but the adjustments offer an opportunity to secure more efficient and equitable taxation in the region.

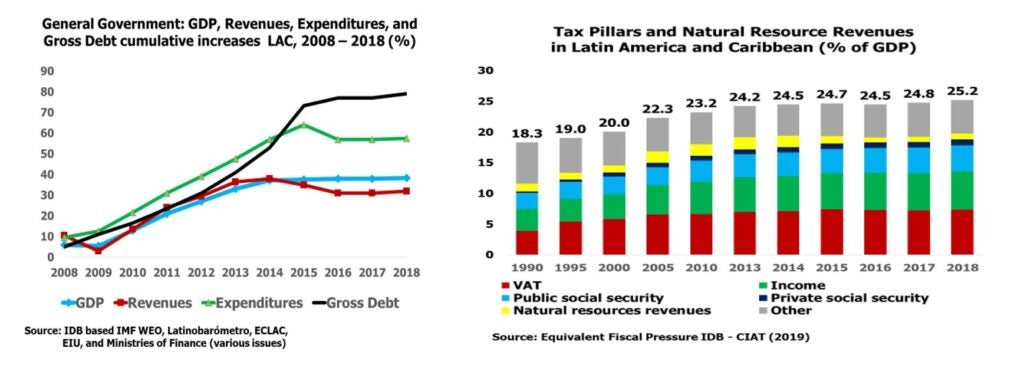

Latin America and the Caribbean: Complex fiscal developments

The aim of this blog is to reflect on what concrete tax policy measures can be implemented after the end of the pandemic in the economic recovery phase.[1] Naturally, the prospects of applying them are specific to each country, since not all countries will have the same urgency of fiscal sustainability, which is already quite compromised (see right-hand panel of the figure below), nor the same capacity to expand the tax space, nor the same institutional strength. Those countries that are better placed at the start will find it easier to implement measures that lead to earlier consolidation in a region that has followed an arduous path to broaden the tax space (see the left-hand panel of the figure). We are aware that revenues are only one factor in the equation, and that countries will need other measures to improve the rationality, effectiveness and transparency of public spending.

Value added tax (VAT)

To start with value added tax (VAT), given its revenue potential, in those countries where there is still some margin it might be necessary to raise the rate, not just the nominal rate but also the actual rate, and consider the rationale for exemptions and reduced rates. In some cases, this increase could be temporary, as a mechanism to finance higher spending during the crisis to protect the most vulnerable groups. Given VAT’s regressive nature, such a measure should be accompanied by some reimbursement for the poorest households—not through new exemptions or reduced rates, but through targeted transfers that offset the tax increase (known as personalized VAT or P-VAT). Implementing them requires a reliable register of beneficiaries, which yields another important added value: knowledge of vulnerable groups that facilitates adoption of more effective social measures. Greater P-VAT revenues could even finance a reduction in social security contributions, thereby fostering employment.[2] On the other hand, the use of non-neutral sales taxes that are regressive and complex to manage is not recommended, not even for reasons of fiscal decentralization. A combination of generalized VAT and mass use of electronic invoicing is technically far better. A tax on bank debits should also be avoided, so as not to restrain financial inclusion in the digital century.

On the other hand, the need for revenue makes it urgent to apply VAT (and income tax) to digitally marketed goods and services. One consequence of quarantine measures has been the growth of consumption from digital platforms, which in some countries is still not taxed, or at least not to the desirable degree. This not only has a negative impact on revenue, but also creates strong unfair competition with traditional sectors, especially with small businesses that are precisely the ones that have been hardest hit by the crisis.

Continuing with indirect taxes, in the case of excise taxes it is first necessary to maximize their revenue potential, since a wide margin persists in several Latin American countries. In general, moreover, these taxes correct negative externalities, such as excessive consumption of sugary drinks, alcohol and tobacco, or fossil-fuel pollution. With respect to these latter taxes, it is desirable to replace ad valorem rates with physical unit rates (ad rem). Another possibility is to consider the sharp fall in the price of oil and its by-products as something temporary, keeping fuels prices for final consumers unchanged (or not entirely transferring the price fall), and regarding the difference as a differential in favor of the state.

Income tax

Given the regressive nature of the crisis and the precarious situation in which many companies will find themselves, one option would be to increase rates on capital returns in those cases where this tax is semi-dualized—that is, on “passive” capital income (dividends, interest, royalties, capital gains, and so on). Moreover, increasing the rates on capital returns in semi-dualized income taxes would encourage investment in the business circuit.

In personal income tax (PIT), there is certainly substantial space in most countries of the region. Moreover, it would be worth considering (where this does not exist) moving to global income tax base by taking advantage of the international push toward transparency. On the other hand, in some jurisdictions it is likely that this tax, coupled to social security contributions, exerts pressure on available revenue, affecting national savings and formal employment. Finally, the COVID 19 surcharge on public officials’ salaries and on pensions (defining a threshold) must be a temporary solution. It is more equitable and efficient, for example, to update payment schemes through a “centralized salary scale” system.

Finally, the current context seems to be a good time to review the rationality of incentives schemes, which should also make contributions during the emergency, and to avoid internal transfer pricing whereby profits are artificially transferred to subsidized areas through intercompany transactions. The “rule of proportion” could be applied, for example, whereby sales to the domestic market by a company in a free zone are deducted from the purchaser’s taxable base in proportion to the ratio of statutory rates between that of the subsidized seller and that of the purchaser.

Property taxation

With respect to property taxes, it is imperative to promote and strengthen those that tax rural and urban residential (with a minimum exempt) and business properties (deductible in the corporate income tax), which are of very low yield in the region. Moreover, they would boost the system’s progressiveness and sufficiency, since these properties tend to reevaluate thanks to public infrastructure projects, ranging from roads to airports. Hence the need to strengthen (nominative) land cadasters and therefore tax decentralization planning, reasserting their nature as a subnational tax. It is also essential to strengthen vehicle tax. This would enhance the system’s progressiveness and help defray the costs of tackling degraded road infrastructure. Moreover, administratively it is very simple to collect.

By contrast, we believe it is much more complex to levy the tax on net wealth or gross assets, given the difficulties of appraising many goods and intangibles, as well as the limited depth and liquidity in Latin American markets, unlike those in countries with more developed stock exchanges. Furthermore, in a region whose access to long-term financing is difficult, it is not advisable to tax invested capital, a scarce factor of production in Latin American countries. It could be a temporary solution to face the emergency, but it is not a good substitute for global income taxation and well-managed taxes on real estate. Neither can these two be replaced by taxing exports of commodities, because that affects their competitiveness—apart from exceptional cases when economic rents are generated, such as an abrupt devaluation (overshooting).

Caution in managing the short term and consistency in managing the long term

With regard to the tax moratoria being introduced in many countries, we believe it is appropriate to stress that they should not become waivers, with the possible (temporary) exception of social security contributions to return to employment, and indeed it is important to point out categorically that they are only pertinent extensions. Moreover, it is important to discriminate by tax type (since they are less desirable in those cases, such as VAT, where the consumer pays in the end but does not benefit from the measure) and by impact and size of the company or sector (since the crisis has not struck them all with the same intensity). To that end, analysis of trends in sales can help to target them. It is also imperative to adjust advances on income that are certain to be much diminished, but to avoid tax reductions because they are not necessary in all cases.

We should acknowledge that the tax pillars are an arsenal of long standing, income tax is more than 200 years old, social security is 150 years old, and VAT will reach its century this decade, so it is crucial to update them. A pandemic must be fought fiscally in the domestic arena by modernizing administration (electronic invoicing, risk models, digital property cadasters, and so on). Above all, however, the international effort at coordination spurred by the 2008 financial crisis must be redoubled (automatic exchange of information, publicly accessible registers of beneficial owners, and so forth) in order to combat evasion and money laundering, as well as unjust tax avoidance.

Let us take this opportunity to build a more efficient and equitable tax policy. Social distancing is a strategy, for the first time global and scientific, in which the right to life takes primacy, especially for the most vulnerable. We trust that this same criterion will guide taxation after the pandemic. To corroborate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes: taxes are the price we pay for a civilized society.

References

[1] The measures proposed herein do not, of course, exhaust all possibilities. There are others that should be borne in mind, such as the possible temporary suspension of taxes that involve a fixed cost for certain sectors, like the aeronautics or hospitality industry; compensation for backward losses in income tax in selected sectors; tax concessions for companies’ compulsory health spending on their return from the pandemic; drawing up lists of high-compliance taxpayers to speed up VAT refunds, and so on. Given the space constraints we will not refer to all of them, especially because they are very specific and temporary.

[2] Use of the funds created by expanding the VAT base in pensions (“pro-pensions” use) is one of the three foreseen in “Solving the Impossible Trinity of Consumption Taxes: The Personalized VAT” (2012) https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/1456. Colombia (Decree 459/2020) began refunding VAT to the most vulnerable this March, and Brazil is considering it in its indirect tax reform (“progressive” use of a Slutsky-type compensation).

Leave a Reply