Promoting private investment -both foreign and domestic – must be the cornerstone of any pro-growth fiscal policy in the post-pandemic period. Governments in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) must ensure that the design and implementation of such policies – which usually involve the use of tax incentives – protect tax revenues and attract the type of investment that can contribute to sustainable and equitable long-term growth.

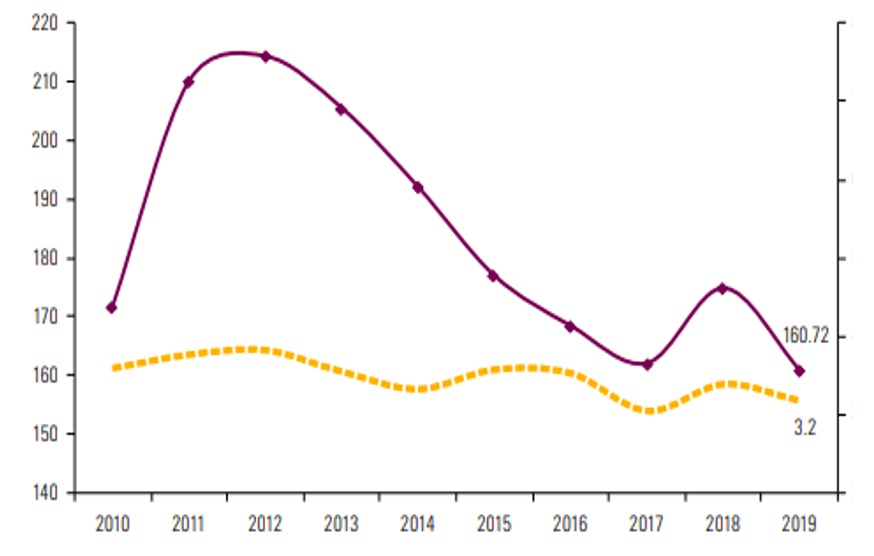

The need to increase investment in LAC is pressing. Foreign direct investment (FDI) into the region has plunged 50 percent[2] in 2020 in the wake of the pandemic, after dropping 20 percent[3] in 2019 from a peak of over US$210 billion in 2012, mainly due to weak economic growth, falling commodity prices and a recovery of rich economies following the global financial crisis. Uncertainty regarding the region’s economic recovery and vaccination rates are likely to keep foreign direct investment at low levels in 2021.

Figure 1 – Foreign Direct Investment Inflows (2010-2019)

(Billions of dollars and percentages of GDP)

Tax policy and the investment climate

In this context, it is likely that policymakers will be looking to implement fiscal policies that contribute to a more favorable investment climate in their countries. Governments may be tempted to use both corporate tax rate reductions and tax incentives to attract FDI.

While the economic literature shows that excessively high corporate tax rates can discourage FDI[4], the effectiveness of such instruments to attract new investment and contribute to a country’s overall growth and employment objectives will depend on their design and implementation. Generous tax reductions or incentives can erode government revenues and cause unintended economic distortions, administrative costs, and corruption[5].

This problem can also be exacerbated if countries feel forced to engage in tax competition to secure investment flows, which would lead them to implement very low rates that undermine the intended positive effects of tax incentives (Abbas and Klemm 2013; World Bank 2018).[6]

Given such challenges, what do countries need to do to implement tax policies that are effective in attracting investment? Here are three recommendations:

#1 – Take into consideration the economic, political and regulatory environment

Globally, the evidence on the benefits of incentives for FDI attraction shows mixed results.[7] Several studies find tax incentives to have limited effects on investment at the aggregate level[8].

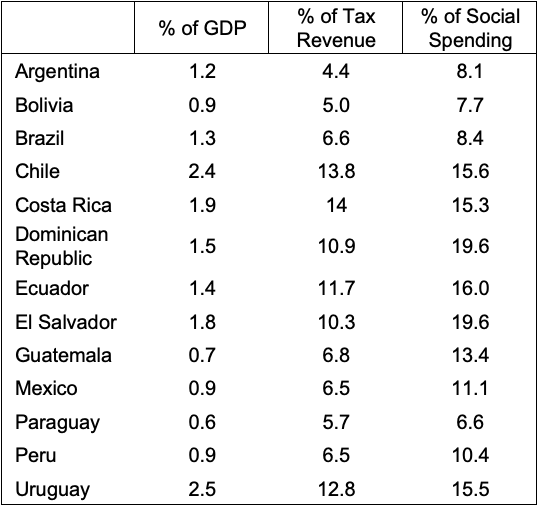

Table 1 – Fiscal Cost of Tax Incentives to Invest in LAC

(2016–2019)

In the case of reductions in the corporate tax rate, for example, a recent study found that in the year following the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), U.S. business investment grew strongly compared to pre-TCJA forecasts. Nevertheless, the study concludes that this effect was primarily the result of rising domestic demand and sales, with the reduction in the corporate income tax rate appearing to have played only a minor role.

Two main reasons seem to be behind these general findings. First, despite being an important factor in investment decisions, taxes are not their main determinant.

Recent evidence from the Global Investment Competitiveness Survey indicates that other variables such as political stability and security, legal and regulatory environment, and domestic market size are more influential to investors than taxes[9]. Thus, it is essential to include these factors into consideration when designing fiscal strategies to attract investment.

Second, the efficiency of tax incentives also plays an important role. Incentives should target investors whose decision is most likely influenced by these incentives, instead of firms that would have invested anyway. Frequently, incentives regimes show inadequate designs and lack of transparency, which reduce their targeting efficiency and generate economic distortions and indirect costs[10].

#2 – Focus on measures that reduce the cost of investment for firms

In LAC, the use of corporate tax rate reductions and tax incentives has been an important part of the region’s strategy to attract investment. Between 2009 and 2015, the average corporate tax rate in LAC decreased to 27% from 29% and a large proportion of countries increased their tax incentives, a similar pattern to the one observed in other developing nations[11].

FDI for countries in the region remained around 3% of GDP[12], while tax expenditure from incentives to invest averaged 1.4% of GDP[13]. Chile and Uruguay (2.4% and 2.5% of GDP, respectively) were the countries with the highest tax expenditures associated to investment incentives, and Paraguay and Guatemala (0.6% and 0.7% of GDP, respectively) were on the opposite end (Table 1). On average, tax expenditures in the region were equivalent to 8.8% of total tax revenue and 12.9% of social spending.

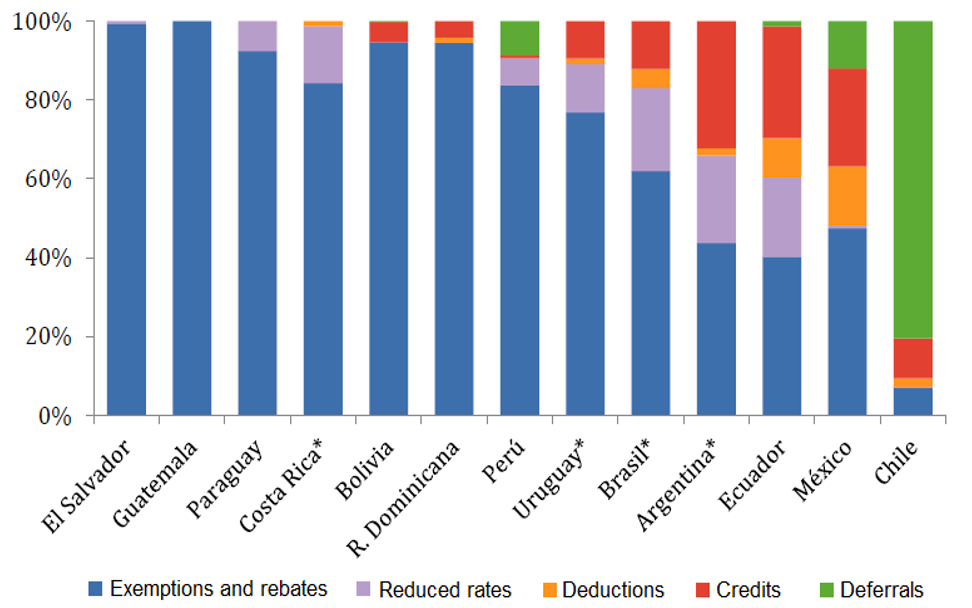

Figure 2 – Tax incentives to invest in LAC, by type

(2016–2019)

With regards to the instruments used, preferential tax measures, such as exemptions (including tax holidays), tax rebates and reduced rates, remain the most widely used type of incentives in LAC (Figure 2).

These types of measures are profit-based, which implies that they are less effective than others as their use is typically unrelated to the amount invested.[14]

In general, the use of cost-based measures, such as tax allowances, tax credits and tax deferrals (such as accelerated depreciation), is preferred, as these instruments directly lower the cost of investment. As a result, they are likely to be more effective[15]. In LAC, Chile leads the region in the use of cost-based incentive measures, followed by Mexico, Ecuador and Argentina.

# 3 – Be aware of the potential impact of a global minimum tax on tax incentives

An important aspect to take into consideration is the current state of discussions regarding Pillar One and Pillar Two of the “OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS)”.[16]

Pillar One focuses on rules for taxable presence (nexus) in countries and profit allocation between countries of multi-national enterprises (MNEs) whereas Pillar Two focuses on a global minimum tax intended to ensure a minimum level of effective taxation on large MNEs. If approved, the provisions under these two pillars will have key implications for the use of tax incentives to attract foreign investment.

The biggest impact is expected to arise from the implementation of a global minimum tax. This is because such a tax would imply that some tax incentives may become ineffective, given that any tax below the minimum that MNEs do not pay in the source country must be paid in the firm’s home country. In turn, this would also imply that some tax incentives may become regressive, as less taxes would be paid in the source country and more in the home country, which represents a transfer of revenue from developing to developed countries.

The measure would primarily affect incentives such as corporate tax holidays and exemptions, which often reduce the corporate income tax rate liabilities to zero[17]. Nonetheless, countries will continue to be able to reduce corporate tax rates and use tax incentives to attract investment as long as the effective tax rates do not fall below the established minimum threshold. Additionally, the provisions under Pillar One and Pillar Two will not apply to all MNEs, as the measures are targeted to large and highly profitable MNE groups only.

Reforms are needed to improve the effectiveness of fiscal incentives

As discussed above, tax policy tools can contribute to attract foreign investment, particularly when considered as part of a broader set of fiscal and non-fiscal measures.

For the LAC region, there is scope to reform the design of the tax incentive regimes used by countries. These reforms should focus on shifting tax incentives towards cost-based instruments, while also including measures to improve their administration and transparency, with the objective of decreasing the indirect cost of tax incentives and enhancing their beneficial effects on investment.

Finally, it is also important that LAC countries consider the potential impact of the tax provisions under Pillar One and Pillar Two of the OECD/G-20 Inclusive Framework, particularly the implementation of a global minimum tax, as this could limit the scope of fiscal policy instruments available to governments to attract FDI.

The IDB has been working closely with its member countries in Latin America and the Caribbean to support the region on their recovery during the post-pandemic period, providing technical assistance, technical cooperation and loans to key strategic sectors. To learn more about our work, check out our Vision 2025.

[1] The authors would like to thank Ubaldo González de Frutos for his useful comments and suggestions to an earlier draft of this article.

[4]Abbas and Klemm 2013; Bénassy-Quéré, Fontagne, and Lahreche-Revil 2005; Desai, Fritz Foley, and Hines 2006.

[5] ECLAC/Oxfam 2019; IMF/OECD/UN/World Bank 2015; World Bank 2018.

[6] This is what is known as the “race to the bottom” in corporate taxation.

[7] In the case of LAC countries, the available evidence is scarce.

[8] James and van Parys 2010; Klemm and van Parys 2012

[9] According to the survey, the share of respondents that considered political stability and security (87%), legal and regulatory environment (86%) and domestic market size (80%) as either critically important or important was significantly larger than for low tax rates (58%).

[11] During this period, 35% of countries in LAC increased incentives in at least one sector, whereas 22% reduced them. This compares to an average of 46% and 24%, respectively, in developing countries (World Bank 2018).

[14] For instance, a 10-percentage-point decrease in the corporate income tax rate only reduces the likelihood of firms considering taxes as an obstacle by 3.6%-4%. Additionally, while empirical research shows that tax holidays also decrease this likelihood (3.3%-6.9%), the link disappears in countries with poor transport or investment climates (World Bank 2018).

[15] ECLAC/Oxfam 2019, World Bank 2018.

[16] OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting.

Leave a Reply