In response to the international crisis of 2008 and the ending of the commodities super cycle (circa 2013), the countries of Latin America reacted with countercyclical policies to tackle the impacts of the global economic downturn. In fact, Latin America’s average fiscal balances deteriorated, from -0.3 percent of GDP in 2006 to -3.6 percent in 2017. Hence fiscal rules (FRs) and their complementary instruments—Medium-Term Fiscal Frameworks (MTFFs) and Independent Fiscal Councils (IFCs)—began to gain importance in the region (Barreix and Corrales, forthcoming).

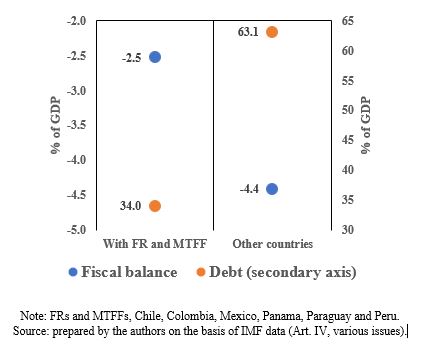

Fiscal rules are mechanisms to support fiscal discipline, establishing numerical goals for budgetary aggregates (Kumar et al., 2009; Kopits and Symansky, 1998). While FRs establish regulatory limits, the budget is the instrument that makes them operational, which essentially is an estimate of revenues with authorization for expenditures. In complementary fashion, there are two other institutions that interact with the FRs and the budget: the MTFFs and IFCs, which not only strengthen the institutional framework of fiscal policy but could also improve its practical application throughout the cycle. Indeed, analysis of the data for Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) reveals that, on average, those countries that have some form of FRs and MTFFs have a better fiscal balance (74 percent less) and a smaller debt (85 percent less) than the average of countries without such instruments (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Non-Financial Public Sector Debt and Deficit as % of GDP, Average for 2015–2017

Figure 1. Non-Financial Public Sector Debt and Deficit as % of GDP, Average for 2015–2017

Medium- and long-term consistency

The MTFF is a tool that helps combine policy design with policy planning and budgeting. A policy means programs and actions to be carried out in a period of more than a year, and that therefore will have consequences for costs in future years (Vega, 2012). The main goal of MTFFs is to extend treasury planning beyond the short term, and it serves as an anchor for governments to commit to fiscal targets, thereby avoiding political biases. A well-designed MTFF makes it possible to draw up credible annual budgets, to provide more precise macro-fiscal projections, to analyze debt sustainability, and to identify fiscal risks. It also facilitates early warnings about the sustainability of ongoing policies (World Bank, 2013) and the introduction of corrective measures. These are not minor attributes, since an MTFF strengthens the credibility and predictability of fiscal policy and lessens uncertainty among agents.

The virtues of a well-designed MTFF confer the power of compliance on the fiscal rule, since they support direct control of spending. At the same time, however, the rule imposes constraints that define the limits within which the budget can move. MTFFs and FRs are therefore complementary. On average, the countries that have adopted MTFFs improved their fiscal positions by more than two percentage points of GDP after implementation, and the more advanced stages of such frameworks (expenditure frameworks with program-level targets, for example) are associated with less volatility in public social spending (Vlaicu et al., 2014).

Additionally, MTFFs: i) encourage political authorities to become familiar with, assess, and correct fiscal behavior; and ii) make it possible to reorient savings, thus improving control of spending and helping to target it on priority programs.

This helps mitigate the two great difficulties of multiyear budgets: i) being based on medium-term projections, they tend to have growing estimation errors, especially in relation to revenues; and ii) by establishing expenditure authorization, they comprise a floor for demands from pressure groups, including tax expenditures, in the annual rendering of accounts (Martirene, 2007). Given the region’s volatility (especially because of its dependence on commodities) and global uncertainty (financial and commercial), it might be more effective to reduce the timeframe of multiyear budgets to three years, for example, and institute an MTFF with robust seven-year projections, as the case may be.

Independent oversight and monitoring

Additionally, the benefits of combining the FR, the regulatory constraint, with the MTFF, the long-term (cycle) projection, is strengthened by the inclusion of independent oversight and monitoring (the IFC). Indeed, Beetsma et al. (2018) find that IFCs improve compliance with the rules of balance and spending, while at the same time enhancing the precision of macroeconomic projections.

IFCs aim to foster commitment to sustainable public finances and avert possible risks. Establishing IFCs that consist of independent specialists of high technical quality is key to fulfilment of their role: ensuring compliance with the rule. In addition to the foregoing, Beetsma et al. (2018) point out that IFCs can also carry out other functions such as: i) providing inputs for the budgetary process; ii) interacting with key stakeholders in the budgetary process and its accompanying MTFF; and iii) raising the reputational costs of financially irresponsible decisions.

The effectiveness of these councils will depend on key factors such as the autonomy of their mandates’ scope, the dissemination of the analysis, and the technical reputation of their members. The evidence shows that the revision of macroeconomic projections reduces estimation biases. IFCs, therefore, complement rather than substitute for the other budgetary institutions (González, 2016). It is also advisable that fiscal councils have greater independence established through legal and operational guarantees. IFCs can thus remain effective through political cycles, attenuating the influence of governments and pressure groups (Debrun et al. 2013).

In Latin America it is important to strengthen these two institutions, MTFFs and IFCs, with a view to improving compliance with fiscal rules so as to strengthen financial stability over a longer time horizon. Efforts should be made to give greater substance to MTFFs, to project over longer timeframes, to include fiscal risk analysis, and to institute obligatory budgetary monitoring. Finally, only four countries (Chile, Colombia, Peru and Mexico) have IFCs, and these were set up only recently.[1] In this regard, the creation of this overseer/advisor would not only improve compliance with the fiscal rule, but would also help in crafting more robust budgets and MTFFs.

References

Barreix, A. and L. F. Corrales. Forthcoming. Reglas fiscales resilientes en América Latina. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank.

Beetsma, M. R. M., Debrun, M. X., Fang, X., Kim, Y., Lledo, V. D., MBaye, S., and Zhang, X. 2018. Independent Fiscal Councils: Recent Trends and Performance. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund.

Cottarelli, C. and Kumar, M. 2009. Fiscal Rules–Anchoring Expectations for Sustainable Public Finances. IMF, Policy Paper.

Debrun, X., Kinda, T., Curristine, T., Eyraud, L., Harris, J., and Seiwald, J. 2013. The functions and impact of fiscal councils. International Monetary Fund, Policy Paper, 16.

González, H. 2016. Consejos Fiscales: Experiencia Internacional y Lecciones para Chile. Libertad y Desarrollo. Serie Informe Económico 259. September 2016.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2018. World Economic Outlook, April 2018. Washington, DC.

Kopits, M. G., and Symansky, M. S. A. 1998. Fiscal policy rules (No. 162). International Monetary Fund.

Kumar, M., Baldacci, E., Schaechter, A., Caceres, C., Kim, D., Debrun, X, and Zymek, R. 2009. Fiscal rules–anchoring expectations for sustainable public finances. IMF Staff Papers, Washington DC. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2009/121609.pdf.

Martirene, R. A. 2007. Manual de Presupuesto Plurianual. Comisión Económica para América Latina (CEPAL), Santiago, Chile.

Vega, A. 2012. Marcos Fiscales y Presupuestarios de Mediano Plazo. Comisión Económica Para América Latina (CEPAL), Santiago, Chile.

Vlaicu, R., Verhoeven, M., Grigoli, F., and Mills, Z. 2014. Multiyear budgets and fiscal performance: Panel data evidence. Journal of Public Economics, 111, 79-95.

World Bank. 2013. Beyond the Annual Budget: Global Experience with Medium-Term Expenditure Frameworks. Washington, DC: World Bank. © World Bank. Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11971 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.

[1] Except Mexico, which since 1998 has had a fiscal council known as the Center for the Study of Public Finances.

Leave a Reply